Researchers have found ancient gases and fluids trapped in 1.4-billion-year-old halite crystals from northern Ontario, Canada. Their analyses directly constrain Mesoproterozoic (1.8 to 0.8 billion years ago) oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations to 3.7% modern levels and 10 times preindustrial levels, respectively. The results show this was a period of equable climate and that atmospheric oxygen concentrations, at least transiently, surpassed the metabolic requirements of early animals long before their emergence.

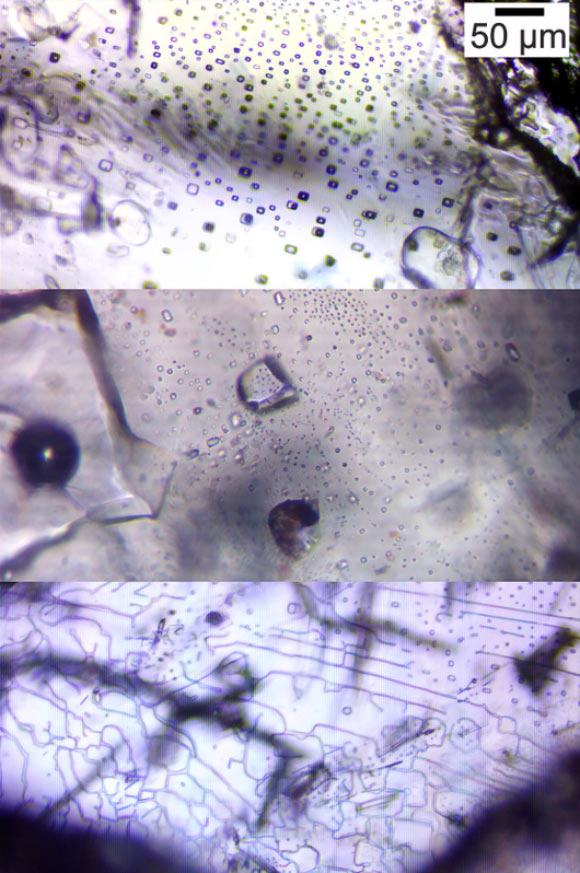

Example photographs of primary, mixed, and secondary halite inclusion assemblages. Image credit: Park et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2513030122.

Scientists have long known that fluid inclusions in halite crystals contain samples of the early Earth’s atmosphere.

But teasing accurate measurements out of those inclusions has proven to be a formidable challenge: they contain both air bubbles and brine, and gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide behave differently in water than they do in air.

“It’s an incredible feeling, to crack open a sample of air that’s a billion years older than the dinosaurs,” said Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute graduate student Justin Park.

“The carbon dioxide measurements we obtained have never been done before,” said Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Professor Morgan Schaller.

“We’ve never been able to peer back into this era of the Earth’s history with this degree of accuracy. These are actual samples of ancient air!”

The readings show that the Mesoproterozoic atmosphere contained 3.7% as much oxygen as there is today, a surprisingly high number, high enough to support the complex multicellular animal life that wouldn’t arise until hundreds of millions of years later.

Carbon dioxide, meanwhile, was 10 times as abundant as it is today — enough to counter the ‘faint young Sun’ and create a modern-like climate state.

One question that naturally arises: if there was enough oxygen to support animal life, why did it take so long to finally evolve?

“The sample captures just a snapshot of geologic time,” Park said.

“It may reflect a brief, transient oxygenation event in this long era that geologists jokingly call the ‘Boring Billion’.”

“It was an epoch of Earth’s history marked by low oxygen levels, widespread atmospheric and geologic stability, and scant evolutionary change.”

“Despite its name, having direct observational data from this period is incredibly important because it helps us better understand how complex life arose on the planet, and how our atmosphere came to be what it is today.”

Previous indirect estimates of carbon dioxide during the period pointed to lower levels incompatible with other observations showing that there were no significant glaciers during the Mesoproterozoic Era.

The team’s direct measurements of high carbon dioxide levels, combined with temperature estimates from the salt itself, suggest that the Mesoproterozoic climate was milder than previously thought — comparable to today’s.

“Ted algae arose right around this point in the Earth’s history, and they remain a significant contributor of global oxygen production today,” Professor Schaller said.

“The relatively high oxygen levels could be a direct consequence of the increasing abundance and complexity of algal life.”

“It’s possible that what we captured is actually a very exciting moment smack in the middle of the Boring Billion.”

The team’s paper was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Justin G. Park et al. 2025. Breathing life into the boring billion: Direct constraints from 1.4 Ga fluid inclusions reveal a fair climate and oxygenated atmosphere. PNAS 122 (52): e2513030122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2513030122