The 2026 Daytona 500, scheduled February 15 as the first points race of the NASCAR Cup Series season, will carry more weight than normal.

Next year’s 500 will mark a pair of key anniversaries. It will have been 50 years since the 1976 500, which featured arguably the most dramatic finish in NASCAR history, and 25 years since Dale Earnhardt’s death on the final lap of the 2001 500.

Related Story

Officials haven’t announced any planned commemorations of the two anniversaries during 500 week, but it’s a virtual certainty that both will be acknowledged in some significant way. Both were key events in very different ways.

Richard Petty and David Pearson entered the 1976 500 as giants of that era of stock car racing. At that point, Petty had won six Cup championships and 177 races. Pearson owned three championships and 87 wins. In 1975, the previous season, Petty won 13 times and got another championship; Pearson had three wins. Only three years earlier, Pearson had won 11 times in only 18 starts.

They were the kings of the superspeedways and often found themselves running one-two in the money laps. Their fan kingdoms ruled the grandstands.

RacingOne//Getty Images

That 500 week started in bizarre fashion. Darrell Waltrip and A.J. Foyt had turned in fast qualifying times in runs for the pole, but both were disqualified when inspectors discovered nitrous oxide additive—used to temporarily boost power—in their cars. This resulted in a very odd Daytona 500 front row of outliers Ramo Stott and Terry Ryan.

The pole qualifying controversy dominated most of the rest of the week, but race day brought the usual big-track story: Would Petty and Pearson battle for the win?

In the closing laps, the two were exactly where many fans expected them to be—in the first and second positions. Petty led entering the final lap. As they roared into the third turn for the last time, Pearson charged alongside Petty on the inside, setting up the fourth turn for ultimate auto racing tension as a full grandstand and a nationwide (ABC) television audience watched.

The finish and the aftermath were so dramatic that ABC delayed switching its telecast to the Winter Olympics.

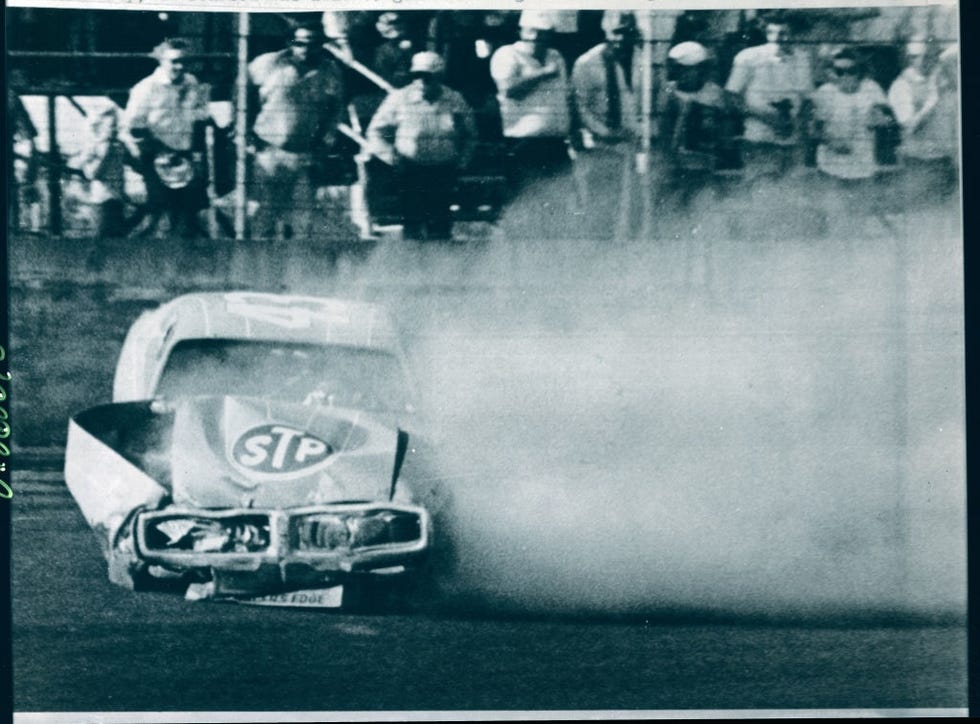

The two cars touched in the tightest spot of the final corner, and the contact sent both into the outside wall and into spins down the track.

“With the draft and all that, the cars were so light all you had to do was just blow on it,” Petty remembered many years later. “I don’t even think it left a mark on the car. That’s how easy we hit. I thought I had cleared Pearson. I really did.”

He didn’t.

For a brief moment, it appeared that Petty might cross the finish line backward to win the race in crazy fashion, but his car fell off the banking and stopped on the grassy area separating the track from pit road.

Pearson’s car also dropped off the track, and he was clipped by Joe Frasson’s car as he slowed. While members of Petty’s crew ran from his pit to the King’s disabled car, Pearson, who had depressed his clutch to keep the engine fired even in the calamity of the wreck, straightened his Mercury and chugged across the finish line at about 30 miles per hour to win the race.

Bettmann

Petty’s crew, including his 15-year-old son Kyle, was ready to head to victory lane and start a fight. Petty, still in the driver’s seat, told them to calm down, push the damaged car back to the garage area, and get ready for the next week’s race at Rockingham, North Carolina.

One writer called the finish “magnificent, heart-stopping, and just a shade ridiculous.”

The finish and the aftermath were so dramatic that ABC delayed switching its telecast to Innsbruck, Austria, for planned coverage of the Winter Olympics.

The win would be Pearson’s only Daytona 500 victory. Petty eventually totaled seven. The duo totaled 63 one-two finishes across the years, with Pearson leading that score 33-30.

Related Story

Twenty-five years later, Dale Earnhardt had tied Petty’s record championship total of seven. He was driving for team owner and long-time friend Richard Childress and had built a winning team of his own at Dale Earnhardt Inc.

Earnhardt started the 2001 Daytona 500 in seventh place and led only 17 laps, but Michael Waltrip, driving one of DEI’s strong Chevrolets, led 27 and had a strong drafting partner in Dale Earnhardt Jr. in another DEI car.

Earnhardt was in the tight pack drafting toward the finish, running behind Waltrip and Earnhardt Jr., on the final lap when chaos erupted between the third and fourth turns. After contact from Sterling Marlin, Earnhardt’s Chevrolet slammed almost head-on into the outside wall, and his car fell off the banking even as Waltrip roared across the finish line to win the 500.

ERIK PEREL//Getty Images

At first look, Earnhardt’s wreck didn’t appear to be any more serious than dozens of other similar crashes at Daytona, but concern grew as it became clear that Earnhardt wasn’t conscious and wouldn’t exit the car on his own. He was removed by safety workers and transported to a nearby hospital. He was pronounced dead there, and NASCAR president Mike Helton soon appeared in a hushed media center to confirm that the sport’s biggest star had passed away.

Earnhardt’s death, the last in a string of driver fatalities on NASCAR tracks, led to a major investigation and resulted in a series of safety advances – both inside race cars and in speedway construction – that changed the stock car racing landscape. In the 25 years since Earnhardt’s death, NASCAR has not experienced another driver fatality.

Mike Hembree has covered auto racing for numerous media outlets, including USA Today, NASCAR Scene, NBC Sports, The Greenville News and the SPEED Channel. He has been roaming garage areas and pit roads for decades (although the persistent rumor that he covered the first Indianapolis 500 is not true). Winner of numerous motorsports and other media awards, he also has covered virtually every other major sport. He lives near Gaffney, South Carolina and can be convinced to attend Bruce Springsteen concerts if you have tickets.