When Cori Lausen wandered into a cavern in the NWT’s South Slave region – one locals had called “the bat cave” – she wondered if it would live up to its name.

Venturing deeper into the cave, she eventually heard a few squeaks.

Dragging themselves past a narrow pinch point in the cave system, she and another biologist entered a larger chamber and began spotting clusters of bats.

“We started counting and we just kept walking and walking,” said Lausen.

That day in September 2010, Lausen and her colleague counted about 3,000 little brown myotis bats. She says that’s the largest known hibernaculum for this species in all of western North America.

“It was actually hard to stay quiet because this is the most amazing thing – we never dreamed we would find a hibernaculum with so many bats in it,” said Lausen.

“It was really hard for us to not all just start hooting and hollering.”

The biologists were doing their best not to disturb the animals, she said, and so communicated mostly through thumbs-up and gestures of excitement.

Lausen, now the Wildlife Conservation Society Canada’s director of bat conservation, said the site holds a special place in her heart.

These days, she’s concerned about the future of the animals she found. Their health could be at risk.

Biologist Cori Lausen is seen exiting a bat hibernaculum in British Columbia before the Covid-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, she said, researchers didn’t wear masks around bats or in their roosts. Since the pandemic, masks have become a requirement to ensure human viruses aren’t spread to bats. Photo: Nelson Star

Biologist Cori Lausen is seen exiting a bat hibernaculum in British Columbia before the Covid-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, she said, researchers didn’t wear masks around bats or in their roosts. Since the pandemic, masks have become a requirement to ensure human viruses aren’t spread to bats. Photo: Nelson Star

Little brown myotis bats, listed as endangered in Canada and of “special concern” in the NWT, are seen in a large hibernaculum in the South Slave that has since earned a place in Lausen’s heart. Photo: Cori Lausen

Little brown myotis bats, listed as endangered in Canada and of “special concern” in the NWT, are seen in a large hibernaculum in the South Slave that has since earned a place in Lausen’s heart. Photo: Cori Lausen

Northern bats are among the last holdouts against white-nose syndrome, which has decimated bat populations across North America since it was first detected in 2006. Now, experts warn the fungus that causes the disease is at the doorstep of the Northwest Territories.

Lausen and a team of researchers are working on a possible remedy that uses bacteria already found on bats to help fight the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome.

If adopted by provincial and territorial governments, Lausen says the strategy she has helped to develop could be scaled up to help shield bats against the looming threat.

Pinpointing the origin

White-nose syndrome is caused a cold-loving fungus called Pseudogymnoascus destructans – often referred to as Pd – that lives in the soil and in bat hibernation sites like caves.

A hibernating bat’s body temperature can drop as low as 3C, an ideal temperature for the fungus to thrive.

The fungus grows by hyphal extension, which gives it the kind of fuzzy appearance you might notice in mould on leftovers.

Pd also reproduces by dispersing spores that can become airborne, said Jianping Xu, a biology professor at McMaster University who studies the evolutionary genetics of fungi.

Xu was part of a research team assembled by New York State that determined fungal isolates – a term for collected strains of fungus – were genetically identical across eastern North America.

“Since then, about 60 isolates from across North America have been sequenced – the whole genome – and we identified they are very, very tightly clustered together. There are very few genetic mutations separating them,” said Xu.

Xu said he and his fellow researchers have been able to track the accumulated genetic mutations to a single origin in upstate New York.

The current hypothesis, Xu says, is that a caver (someone with an interest in exploring caves) was responsible for bringing the fungus to North America, possibly on a piece of clothing.

“Because this is a relatively new fungus in North America – it did not exist in North America – it found its ecological niche and probably relatively few competitors, therefore it was able to expand rapidly,” Xu said.

White-nose syndrome has wiped out some bat colonies in eastern Canada and the US. Lausen described “a complete die-off” at hibernacula in the east.

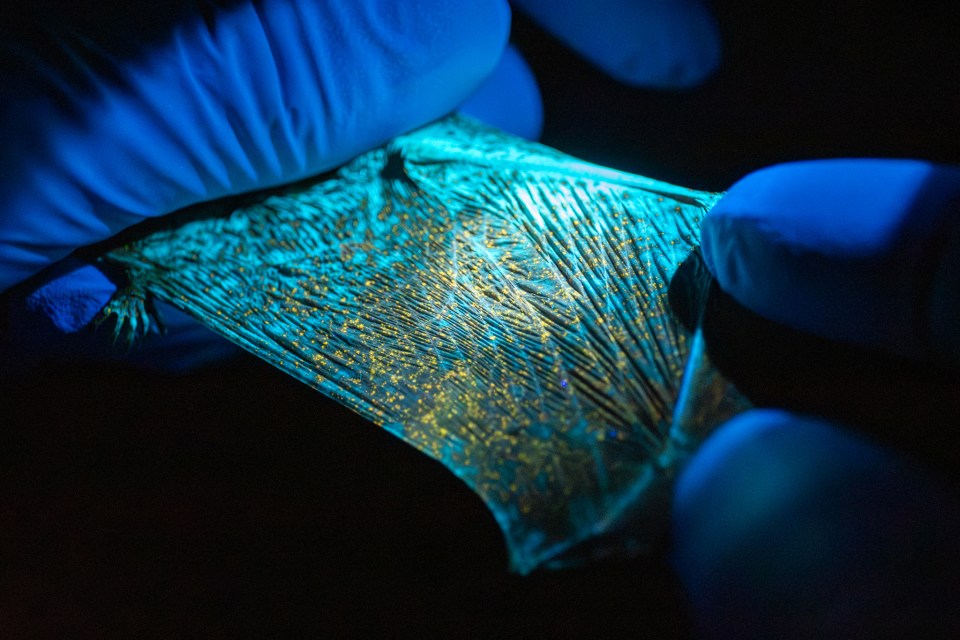

The fungus disrupts bats’ hibernation, forcing them to use their fat reserves to heat their bodies back up, restart their immune systems and groom the fungus off their skin before it causes damage, Lausen said.

“They can get away with that only a little bit in the winter before they burn through too much fat and die,” she said.

Even if they do survive interruptions in their winter slumber, Lausen said, Pd can eat through the skin on a bat’s wing, causing holes that render the bat flightless and unable to feed itself.

Pd is seen on an Alberta bat’s wing under UV light. Photo: Jason Headley

Pd is seen on an Alberta bat’s wing under UV light. Photo: Jason Headley

Gradually, white-nose syndrome has been making its way across the continent.

It was detected in northern Manitoba in 2021 and in southern Saskatchewan in 2022. That same year, Pd was found in bat droppings in southeastern Alberta.

Lausen said Pd has since been found near Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta. The park spans the Alberta-NWT border.

But Lausen added researchers still don’t know much about the impact of white-nose in western North America.

“It’s behaving differently. The spread is different,” she said.

“All we know for certain is that it’s doing something different than it did in the east.”

A protective ‘cocktail’

Lausen and a team of researchers have spent the better part of the last decade working on a way to shield bats from the deadly disease using a “cocktail” of different types of bacteria already found on the animals.

The project began after a microbiologist at Thompson Rivers University, Naowarat Cheeptham – known by her peers as Ann – contacted Lausen to ask if she could help.

Cheeptham had been in touch with a colleague, Diana Northup of the University of New Mexico who had found that some bacteria on bat wings got in the way of Pd.

The team at WCS Canada began swabbing the wings of hundreds of bats and sending the samples to Thompson Rivers.

Scientists there drew up a list of a handful of bacteria that could be useful in the fight against Pd.

Jianping Xu and his team at McMaster University also analyzed the samples, looking for bacteria exhibiting “anti-Pd activity.”

In a petri dish, Xu said, this can be identified by a clear ring – a “zone of inhibition” – where bacteria placed in the centre of the dish would prevent Pd spores from growing.

Xu’s team helped narrow down the list to four strains of bacteria for the anti-Pd cocktail.

In 2018 and 2019, Lausen and her team ran two captive trials to prove the cocktail was safe and that it worked.

By 2022, they had begun a program in the US state of Washington, treating bat boxes at three sites with the cocktail and leaving another three sites untouched as a control group.

All three untreated sites now show evidence of white-nose syndrome in their bat population, Lausen said. At one, 98 percent of the bats have died.

However, none of the sites treated with the cocktail show any evidence of the disease.

While this is promising evidence, Lausen said, it isn’t entirely conclusive. The number of sites is small and the results could have occurred by chance.

However, she said, the research showed enough promise to convince Alberta to begin applying the cocktail to 19 bat boxes this past summer.

She said those efforts will be scaled up next summer with help from WCS Canada.

WCS Canada staff Susan Holrody and Cory Olson spray an Alberta bat box with the cocktail. Photo: Jason Headley

WCS Canada staff Susan Holrody and Cory Olson spray an Alberta bat box with the cocktail. Photo: Jason Headley

Lausen said the province has “nothing to lose” by trying the treatment.

“They’re watching bats die. They’ve had 80 percent die off at one of the first colonies that they discovered white-nose syndrome in, within one year,” said Lausen.

“Alberta has run out of time, and so that’s why they are moving more quickly.”

She worries the NWT might be in a similar position in the near future.

Application in the NWT

Joanna Wilson, a wildlife biologist at the NWT’s Department of Environment and Climate Change, describes white-nose syndrome as a “looming threat” to the territory’s bats.

The department is assessing the cocktail developed by Lausen and her team.

“We’ve been interested – especially as white-nose gets closer – and we’ve been watching the outcomes of their project and wondering whether it would make sense to try and do something like that here,” said Wilson.

She said ECC has been working to establish the kinds of bacteria found on bats in the NWT, since the cocktail relies on strains found on bats in BC.

ECC wants to know whether that means the cocktail will work here, or if there are different bacteria that would necessitate starting from scratch.

So far, two of the three species of bacteria used in the BC cocktail have been found on bats in the NWT, Wilson said.

A bat is swabbed as part of ECC’s monitoring program. Photo: Arianne Depot

A bat is swabbed as part of ECC’s monitoring program. Photo: Arianne Depot

“We want to keep looking, get more information, and see if the third one’s out there,” said Wilson.

She said ECC collected more swabs this past summer and the work is scheduled to continue in the summer of 2026.

“While it is possible that Pd fungus could arrive any time now, we’ve seen in other regions that there is usually a time lag between the first detections of Pd and when impacts of white-nose syndrome start to be seen in the bats,” said Wilson.

“We think we still have a bit of time to get our ducks in a row before proceeding with treatments.”

‘A lot of things we don’t know’

There are some reasons for optimism.

For example, Lausen said, white-nose appears to be taking hold more slowly on the west coast than it did in the east.

“I truly am optimistic and that’s because of the huge delay that we have seen between the fungus being discovered and bats actually dying in the west,” she said. “That delay wasn’t seen in the east.”

At one site in Washington, she said, Pd was found back in 2020 but there is still no evidence of white-nose syndrome in the local bats.

This could be due to the shorter hibernation cycles of bats in Washington, she said, meaning less exposure to the fungus and a shorter time window in which their winter slumber can be disturbed.

However, Wilson and Lausen agree that may not bode well for northern bats who spend more time hibernating through colder, longer winters.

“There’s a lot of things we don’t know about how our bats will react,” said Wilson.

With the migration of white-nose looming, Wilson says it’s important to reduce other threats so bats have “the best chance of being resilient and fighting it off.”

That includes how people handle bats roosting in buildings. ECC has prepared a guide, for people who might have bat tenants.

If bats need to be excluded from a building, Wilson said, alternative habitats can be created by building and installing bat boxes nearby.

It’s also helpful to report any bat sightings to ECC, the department said, so researchers can better understand where bats are across the territory and how diseases could potentially spread.

“I have a database of those observations and we’ve learned some interesting things from people, especially where there are sightings outside what we might think of as the known range or at an odd time of year,” said Wilson.

She said it’s helpful to know the date and location of a sighting, and to receive photos and video that could help identify the species.

Any bats found dead should also be reported, she said, so ECC can collect them and have them tested.

Related Articles