Denys Kotochihov copies the word gastrointestinal into an artificial intelligence platform on a school laptop, then types “easy explanation.”

The Grade 8 student is demonstrating one way he uses AI.

“The hard words I can’t understand, I’m using AI to help me with,” he says.

Kotochihov’s first language is Ukrainian. He didn’t start learning English until he arrived in Manitoba three years ago. AI is playing a role.

For example, if he doesn’t know a word in English, AI helps with the translation.

“My teacher will give me feedback, I should check information, what it gives me,” he says.

With the ability to access AI at our fingertips, young people are finding ways to put it to use. As the Winnipeg School Division works to adapt to the technology, CBC spent time at General Wolfe School to find out how they’re doing it.

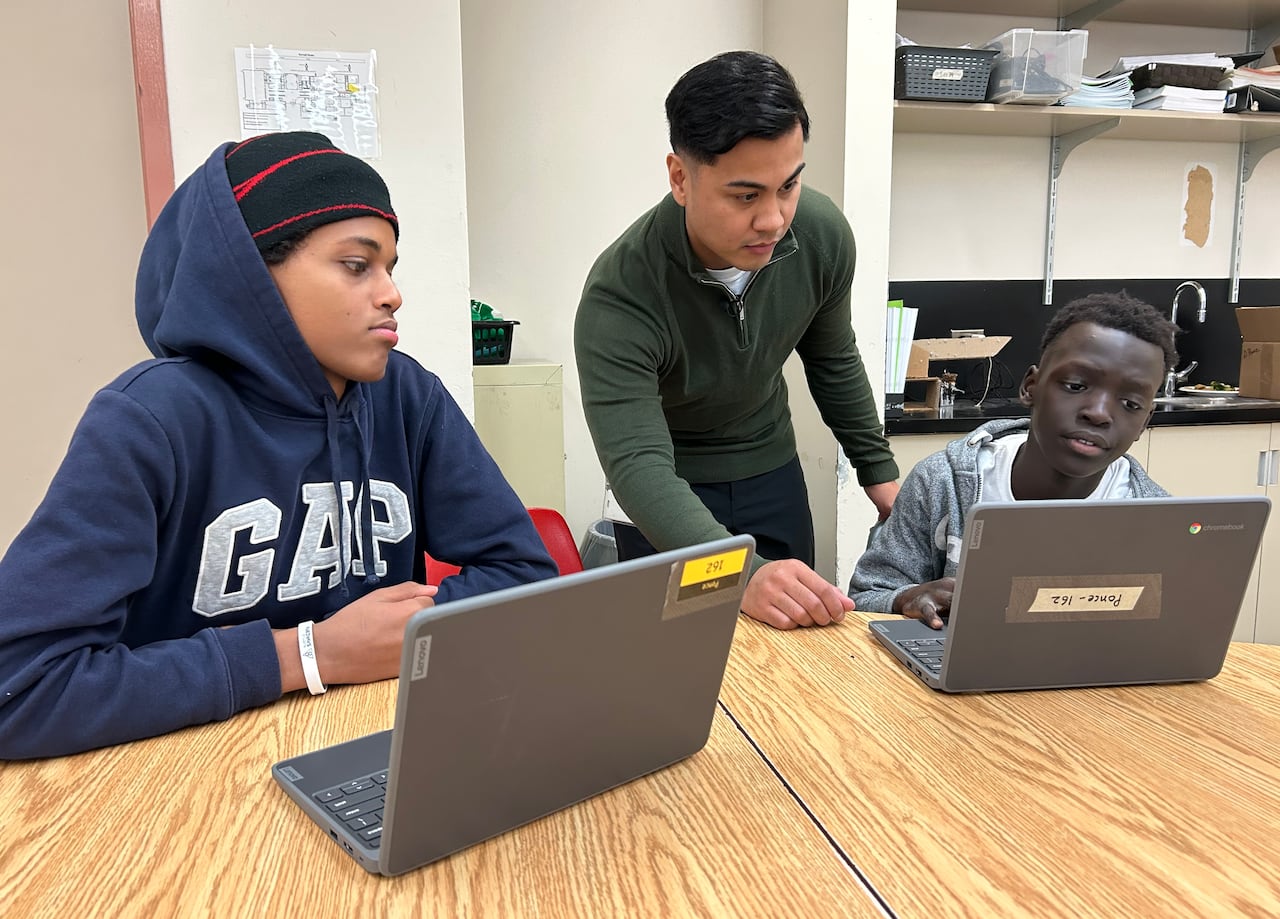

General Wolfe School teacher Donovan Ponce says he starts introducing conversations around AI after first teaching students traditional ways to research. (Alana Cole/CBC)

General Wolfe School teacher Donovan Ponce says he starts introducing conversations around AI after first teaching students traditional ways to research. (Alana Cole/CBC)

Chuol Monybuny, one of five students CBC spoke with, reads a list of facts about cardiac surgeons, part of a project involving the circulatory system.

The Grade 8 student said he used AI to help search for professions related to the topic.

He makes sure what he’s reading is accurate, he said.

“I saw the list of what it was saying, and then after, I went to the trustable sources and see if it lined up,” Monybuny said.

WATCH | Winnipeg students talk AI in the classroom:

See how these students put AI to use at school

If you ask children about artificial intelligence, they’ve probably heard of it, used it and might already have opinions about it. But how is it being used in the classroom? CBC visited one Winnipeg school to find out.

When students at the school start learning about AI depends on the teacher, said Donovan Ponce, a Grade 7 STEM teacher, as well as a project-based learning support teacher.

He thinks with how prevalent AI has become, “students need to learn how to navigate it responsibly.”

“We’re in the age of information, but we’re in the age of, like, misinformation as well,” Ponce said.

“There’s so many things that students can see on their social media feeds that I want them to question the validity of it. So I think there’s so much AI-generated content online that we need to teach students how to discern from real and fake information.”

Ponce, a Grade 7 STEM teacher and project-based learning support teacher at General Wolfe School, says students need to learn how to use AI responsibly. (Warren Kay/CBC)

Ponce, a Grade 7 STEM teacher and project-based learning support teacher at General Wolfe School, says students need to learn how to use AI responsibly. (Warren Kay/CBC)

Ponce is quick to point out the way he teaches students to use AI is “always student- or human-centred rather than AI led.”

“I want students to take ownership of their learning and use AI as a tool to kind of progress their learning further,” he said.

When it comes to working AI into the classroom, Ponce starts the year off teaching his Grade 7 students how to find credible sources using traditional research tools, such as books and the internet.

Later in the year, he starts to “open the door on AI,” he said, which includes helping students practice questioning skills and checking information with credible sources.

Ponce knows there are concerns when it comes to information being copied and pasted, something he noticed in certain cases when AI first started to become popular a few years ago.

It’s one of the reasons he makes sure students understand how to paraphrase, he said.

“The more and more you see AI, the more you can tell some of the sentence structures or some of the symbols commonly used by AIs,” Ponce said.

“So then it’s just showing students that if they copy and paste, your teachers can tell, and that’s not helping them with their learning.”

Matt Henderson is the superintendent of the Winnipeg School Division. (Warren Kay/CBC)

Matt Henderson is the superintendent of the Winnipeg School Division. (Warren Kay/CBC)

The Winnipeg School Division doesn’t have specific policies on AI but worked with senior administration, teachers and families in developing a “thinking framework,” Supt. Matt Henderson said.

“We feel that creating a policy at this point would be not the right pathway, just because the technology is changing so quickly,” he said.

The framework, in part, aims to encourage all 6,000 of the division’s staff to consider a number of questions when teaching, such as are they educating students about AI and what drives it, as well as who benefits from the technology and what the ramifications are.

“When might it assist us, but when is it important that something is coming from human cognition?” Henderson said.

The school division has a number of teacher groups coming together to examine how AI factors into the classroom, including in partnership with Red River College Polytechnic and the University of Winnipeg faculty of education, he said.

He points out the framework also calls on educators to consider the late Murray Sinclair’s four questions: Where do I come from? Where am I going? Why am I here? Who am I?

“I put into a query in a model once, you know, ‘Who am I as Matt Henderson?’ and it said … I’m superintendent of Winnipeg School Division,” Henderson said.

“Well, I’m much more than that. It can’t possibly answer that existential question for me. And so I think slowing it down that way, having students really think about what is unique about human cognition, about humanness, and why would we want to preserve that?”