As we age, we don’t recover from injury or illness like we did when we were young. But new research from UC San Francisco has found gene regulators that turn genes on and off that could restore the aging body’s ability to self-repair.

The scientists looked at fibroblasts, cells found throughout the body that slow down due to aging, leading to wrinkles and poor healing.

The scientists found telltale signs of decline in the way that old fibroblasts expressed, or turned on or off, their genes. A computational analysis of these changes led the scientists to a set of gene regulator proteins, known as transcription factors, that might reverse these age-related changes, along with some of the consequences of aging.

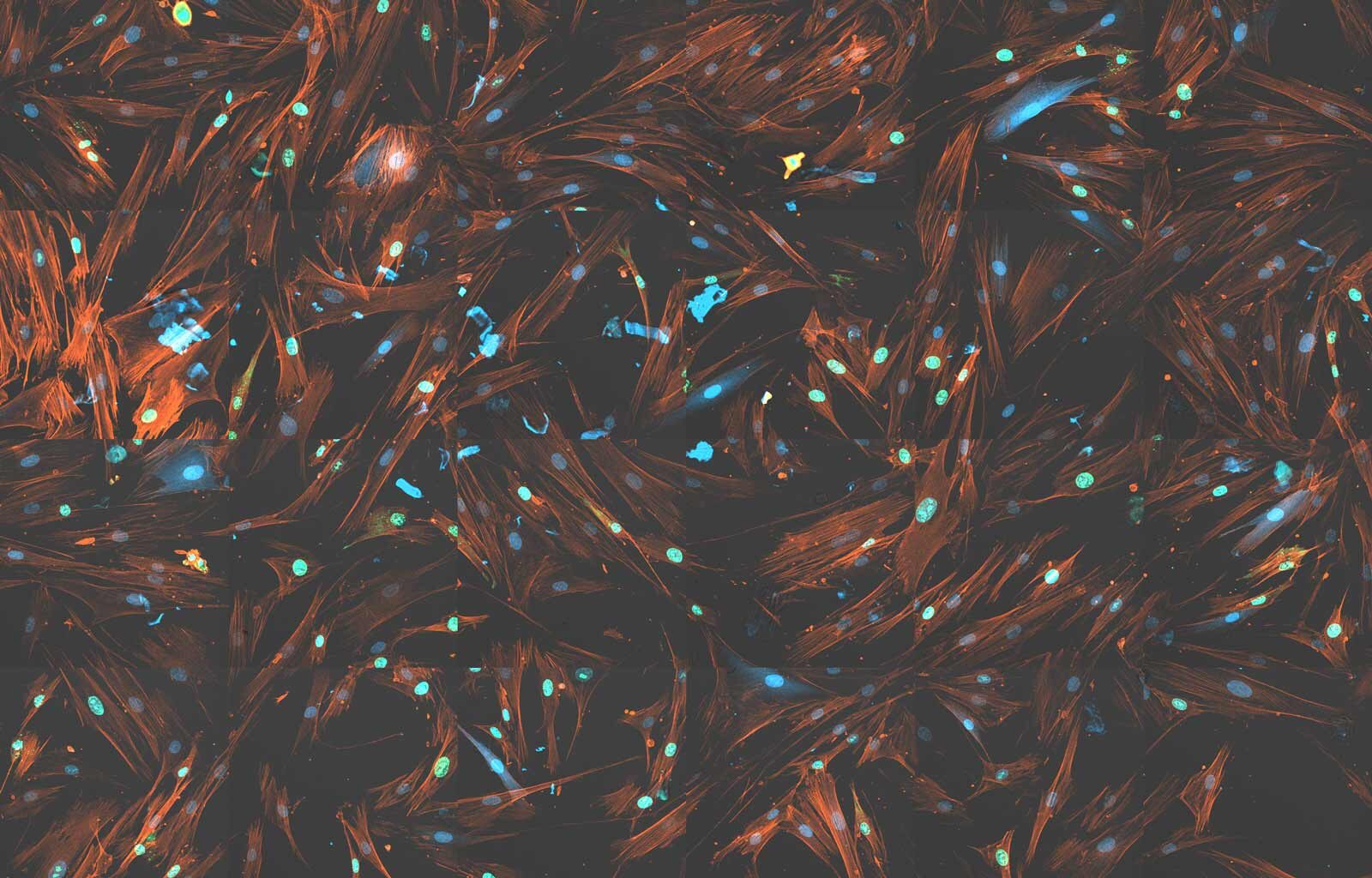

UCSF scientists engineered old fibroblast cells to turn their genes on and off in the same way as young fibroblasts. The old fibroblasts were rejuvenated: they multiplied (green) and produced more of the material used to make the “skeletons,” or extracellular matrix, of our organs (red). Image by Li Lab

“By altering gene expression using the transcription factors we identified, old fibroblasts behaved as if they were younger and improved the health of old mice,” said Hao Li, PhD, UCSF professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics and senior author of the paper, which appears Jan. 9 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Li’s team first compared the way that young and old fibroblasts turned genes on or off as they grow in petri dishes and used computational modeling to find out which regulators were driving this kind of aging.

Next, they used CRISPRa — a variant of CRISPR gene editing — to prompt the regulators to turn on “young” gene expression in old fibroblasts.

Adjusting the levels of any one of 30 regulators triggered young gene expression in old fibroblasts. Changes to the levels of four of these factors improved metabolism in the old fibroblasts as well as their ability to multiply.

In collaboration with UCSF’s Saul Villeda, PhD, an associate professor of Anatomy, they demonstrated that higher levels of the factor EZH2 rejuvenated the livers of mice that were 20-months-old, which is equivalent to about 65 human years. It reversed liver fibrosis; cut the amount of fat that accumulated in the liver in half; and improved glucose tolerance.

“Our work opens up exciting new opportunities to understand and ultimately reverse aging-related diseases,” said Janine Sengstack, PhD, who led the project as a graduate student in Li’s lab and is the first author of the paper.

Other UCSF authors are Jiashun Zheng, PhD, Turan Aghayev, MD, PhD, Gregor Bieri, PhD, Michael Mobaraki, PhD, Jue Lin, PhD, and Changhui Deng, PhD.

Funding: Work was funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG083524, R01AG058742), American Federation for Aging Research, and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub.

Disclosures: Li and Sengstack are co-founders of Junevity. Villeda consulted for The Herrick Company, Inc. Li, Sengstack, Deng, and Zheng hold shares in Junevity. Li, Sengstack, Deng, and Zheng are authors of the patent application: WO/2024/073370 relating to cell rejuvenation.