Dark, cold, and whipped by supersonic winds, ice giant Neptune is the eighth and most distant planet in our solar system. (Credit: Dnl555 on Shutterstock)

Findings Solve Decades-Old Mystery About What’s Inside Uranus And Neptune

In A Nutshell

Scientists discovered a strange form of water that’s simultaneously solid and liquid; oxygen atoms lock into a crystal while hydrogen flows freely

Using the world’s most powerful X-ray lasers, researchers found this “superionic ice” has a jumbled structure that mixes two different crystal arrangements

This form of water likely exists inside Uranus and Neptune, and might explain why these planets have weirdly tilted magnetic fields

The discovery resolves years of contradictory experimental results and confirms predictions made by quantum computer simulations

Water compressed by atmospheric pressure millions of times stronger than on Earth doesn’t behave like the H20 we all know. At extreme conditions found deep inside ice giant planets, scientists have captured the clearest picture yet of “superionic ice,” which is the name for a strange state where oxygen atoms lock into a crystal while hydrogen atoms flow freely like a liquid. This unusual state can be likened to a molecular prison where the bars are solid but the prisoners run wild.

Researchers using the world’s most powerful X-ray lasers compressed water samples to pressures reaching 180 gigapascals (nearly 1.8 million times Earth’s atmospheric pressure) while heating them to thousands of degrees. At these extremes, the team observed something theorists had predicted but never clearly seen: the oxygen atoms don’t arrange themselves into a simple, orderly pattern. Instead, they form a jumbled structure that mixes two different arrangements, constantly switching back and forth like a crystal that can’t make up its mind.

Superionic Water On Uranus And Neptune

Uranus and Neptune likely contain vast oceans of this superionic water deep in their interiors. These planets aren’t made of regular ice despite being called “ice giants.” Pressures and temperatures crush water into this weird superionic state, which might explain some of the puzzling features recorded on these distant worlds, including their tilted, off-center magnetic fields that don’t align with how the planets spin.

Previous experiments had yielded contradictory results. Some teams reported seeing one crystal structure at certain conditions, while others observed completely different arrangements at similar pressures and temperatures. The confusion had persisted for years.

These most recent measurements, published in Nature Communications, may finally solve the mystery. By timing ultrafast X-ray pulses precisely with laser-driven shock compression, the team captured diffraction patterns with far better resolution than earlier attempts. The X-ray pulses lasted just 50 femtoseconds (if a femtosecond were stretched to one second, a second would last 32 million years). These measurements essentially froze the water’s structure before it could change.

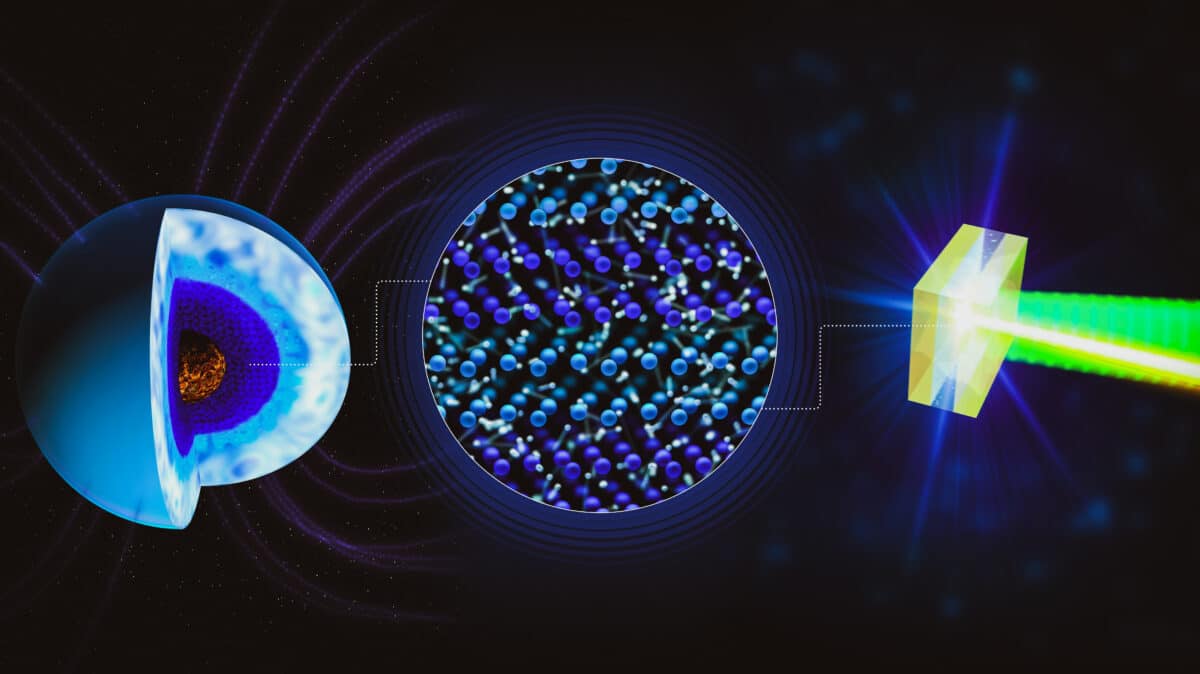

Schematic representation of the microscopic structure of superionic water, in which the oxygen atoms form a solid crystal lattice, while hydrogen ions are virtually free to move within it. With the aid of powerful lasers, this extreme state, which otherwise only occurs inside large planets, could be measured experimentally. (Credit: Greg Stewart / SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

Nature’s Compromise Under Pressure

At moderate pressures (below about 120 gigapascals), the experiments detected two different crystal structures existing side by side. Some researchers had suggested temperature differences might cause this, but the new data points to something more interesting: both arrangements are so close in energy that water genuinely can’t pick one.

Computer simulations predicted this behavior. At these conditions, the energy cost of forming either structure is nearly identical, so water molecules crystallize into whichever pattern happens to work out locally.

As pressure climbs above 150 gigapascals, one arrangement dominates. However, there is a twist. Roughly 25 to 32 percent of the layers stack in a different pattern, creating disorder woven throughout the crystal. Machine learning simulations trained on quantum calculations of water’s behavior produced virtually identical patterns to what the experiments measured. This confirms the disordered structure is real, not just a quirk of how the samples were compressed.

How They Did It

Getting water to these extreme states required sandwiching thin water layers (about half the width of a human hair) between diamond windows. Powerful laser pulses blasted the diamond, generating shock waves that bounced back and forth, compressing the water in steps rather than all at once. Each experiment lasted only nanoseconds and destroyed the target, so the team repeated the process multiple times to verify their results.

At the lowest pressures studied (around 25 to 50 gigapascals), they found simpler, more orderly ice structures. But as pressure increased, the mixed, disordered patterns emerged.

The Bigger Picture

Whether this stacking disorder is permanent or just temporary remains unknown. Similar defects show up in regular ice that forms quickly, then gradually reorganizes. If the superionic defects are temporary, they might not affect planetary interiors much. But if they’re stable, they could change how heat and electricity move through the material, and that matters for magnetic fields.

The flow of charged hydrogen ions through the oxygen lattice generates magnetic fields through what’s called dynamo action. Any structural feature that channels or blocks that flow could alter the field’s strength and shape. Scientists have proposed various explanations for why Uranus and Neptune have such weird magnetic fields, and the internal structure of superionic water might be part of the answer.

Water seems simple (just two hydrogen atoms bonded to oxygen) yet it forms at least 19 different kinds of ice depending on pressure and temperature. Add in superionic variants and this newly discovered disorder, and water starts looking less like a basic substance and more like something with secrets still waiting to be uncovered.

This research reconciles years of contradictory measurements. Earlier experiments using diamond anvil cells reported the wrong structures or transition temperatures that differed by hundreds of degrees. The new data suggests mixed phases and stacking disorder explain peaks that earlier work misinterpreted as pure structures.

Models of Uranus and Neptune’s interiors rely on mathematical descriptions of how materials behave under pressure. These descriptions are often based on theoretical calculations. When experiments confirm those calculations weren’t just math but actual predictions of real physical structures, it means the interior models are probably on the right track.

The phase diagram of water at high pressures remains incompletely mapped. Higher pressures, different temperatures, and longer observation times might reveal additional surprises. Water continues to prove it’s one of nature’s most complicated molecules.

Paper Notes

Limitations

The experiments used shock compression on nanosecond timescales, creating dynamic conditions different from the static equilibrium inside planetary interiors. Rapid compression might induce structural features that wouldn’t appear under slower conditions. The study cannot determine whether the observed disorder represents a stable phase or a temporary configuration specific to shock loading.

Temperature and pressure values rely on computer simulations calibrated to velocity measurements, introducing uncertainties. The equations used are well-established but carry their own margins of error.

The stacking fault model fits the data well but shows small systematic discrepancies near certain peaks, suggesting the actual structure is more complex than the simplified model. Each target was destroyed during measurement, preventing time-resolved studies of how the structure evolves.

Funding and Disclosures

This research was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the PROPICE project (grant ANR-22-CE92-0031 and DFG Project 505630685) and the DFG Research Unit FOR 2440. Additional support came from the Helmholtz Association (VH-NG-1141 and ERC-RA-0041), GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung (R&D project SI-URDK2224), DFG Project 495324226, the European Union ERC MEGACHEM (Grant 101171289), French computational centers TGCC and CINES through GENCI project GEN15731, the North German Supercomputing Alliance under Grants mvp00018 and mvp00026, and the US DOE Fusion Energy Sciences, DOE NNSA SSGF program, and UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship (Grant MR/W008211/1).

Use of the Linac Coherent Light Source at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Experiments were conducted at the European X-ray Free-Electron Laser under proposal 4463.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publication Details

Authors: L. Andriambariarijaona, M. G. Stevenson, M. Bethkenhagen, L. Lecherbourg, F. Lefèvre, T. Vinci, K. Appel, C. Baehtz, A. Benuzzi-Mounaix, A. Bergermann, D. Bespalov, E. Brambrink, T. E. Cowan, E. Cunningham, A. Descamps, S. Di Dio Cafiso, G. Dyer, L. B. Fletcher, M. French, M. Frost, E. Galtier, A. E. Gleason, S. H. Glenzer, G. D. Glenn, Y. Guarnelli, N. J. Hartley, Z. He, M.-L. Herbert, J.-A. Hernandez, B. Heuser, H. Höppner, O. S. Humphries, R. Husband, D. Khaghani, Z. Konôpková, J. Kuhlke, A. Laso Garcia, H. J. Lee, B. Lindqvist, J. Lütgert, W. Lynn, M. Masruri, P. May, E. E. McBride, B. Nagler, M. Nakatsutsumi, J.-P. Naedler, B. K. Ofori-Okai, S. Pandolfi, A. Pelka, T. R. Preston, C. Qu, L. Randolph, D. Ranjan, R. Redmer, J. Rips, C. Schoenwaelder, S. Schumacher, A. K. Schuster, J.-P. Schwinkendorf, C. Strohm, M. Tang, T. Toncian, K. Voigt, J. Vorberger, U. Zastrau, D. Kraus, and A. Ravasio

Journal: Nature Communications | Title: Observation of a mixed close-packed structure in superionic water | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67063-2 | Published: December 7, 2025 (online); Volume 17, Article 374 (2026) | Affiliations: Authors represent institutions including Laboratoire LULI (France), Universität Rostock (Germany), CEA (France), European XFEL (Germany), Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (Germany), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (USA), Queen’s University Belfast (UK), Stanford University (USA), IMPMC (France), ESRF (France), and DESY (Germany).