For nearly 50 years, Bangladesh has been one of the world’s favourite outliers. Born in the trauma of 1971 with a shattered economy and a population of 75 million, the country was summarily dismissed as a “basket case.” Yet, through a mix of resilience and grassroots innovations, the country proved pessimists wrong. We defeated cholera with saline, lowered birth rates with an army of door-to-door social workers, fuelled growth with the labour of our daughters in garment factories, and kept food insecurity at bay through technological adaptation in smallholder agriculture and the building of value chains.

However, as we cross the quarter-century mark in 2025, a sobering confrontation with reality has become inescapable. The “business as usual” model, built on frugal innovation and cheap labour, has hit a structural ceiling. We are no longer fighting the survival battles of the 1970s. We are confronting four colliding shifts—in our population, our cities, our economy, and our schools—that are far more complex, costly, and politically contentious than the challenges of the past.

Data from recent PPRC research pose a hard question: while policymakers, development partners, and the cognoscenti invoked the rosy language of the “demographic dividend,” did the ground beneath us quietly shift? The central challenge of Bangladesh today is no longer how many people it has, but how little margin each household has left to survive. When families operate this close to the edge, progress is no longer automatic. The evidence suggests that the gains of the past are now being tested in ways we have not faced before. We appear to be approaching a tipping point, where policy drift and household insolvency together threaten to undermine a generation of achievement.

The demographic drift: Losing the signals

Bangladesh’s early success in stabilising population growth was the result of a calibrated strategy. In the 1970s and 1980s, the country deployed a door-to-door family planning model that bypassed husbands and conservative elders who often blocked women’s choices. Mass media and religious leaders were mobilised to shift social norms, embedding family planning into everyday life.

Between 2010 and 2020, however, the strategic signal began to fade. Population increasingly came to be treated uncritically as a “resource” rather than as a challenge to be actively managed. The door-to-door system was allowed to weaken in favour of fixed community clinics, overlooking a basic reality: for poor households, even a short trip to a clinic can be logistically or financially challenging.

The latest fertility data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey signal that fertility decline has stalled at around 2.3 children per woman. More troubling still, Bangladesh now records an adolescent pregnancy rate of 113 per 1,000—one of the highest outside Sub-Saharan Africa. This is not merely a health statistic; it represents a structural economic trap.

Consider the financial reality of the average household. The PPRC State of the Real Economy Survey of 2025 puts monthly income at roughly 32,685 takas, while monthly expenditure is about 32,615 taka. The 70-taka surplus tells us that families are barely breaking even.

A stalled demographic transition magnifies household fragility. Many families are already engaged in what can only be described as caloric triage, cutting beef, milk, and chicken from their diets simply to cover rent and utilities. Solvency becomes a daily gamble: a choice between paying the landlord or buying milk, between a daughter’s school fees or a father’s insulin. For millions of households, these are not metaphors but nightly calculations, made at the kitchen table with a shrinking wallet and no margin for error.

In such conditions, an unplanned pregnancy, an early marriage, or a health shock can tip a household from precarious balance into deep poverty. Child marriage, often explained as culture, is in many cases an economic coping strategy. By pushing young girls out of school and into dependency before any human capital can form, child marriage converts short-term survival into long-term economic loss, locking the next generation into asset depletion.

The urban trap: A lopsided nation

The second collision is spatial. Bangladesh has moved from villages to cities, but in a lopsided way, centred overwhelmingly on Dhaka. Urbanisation was long assumed to be an automatic engine of wealth accumulation. Our data are now telling us otherwise.

Bangladesh is facing an urban trap. While city incomes appear higher on paper, at around 40,000 taka per month, the high cost of living erases much of that advantage. Housing alone consumes about 9 percent of the urban household budget, compared with just 1 percent in rural areas. For many families, higher wages are swallowed whole by rent.

Dhaka is buckling under its own weight. Functional second-tier cities were never adequately built; even Chattogram struggles with liveability and governance. Instead of reaping the benefits of density, Bangladesh is witnessing the rise of a new urban poor: families who appear solvent but remain one crisis away from ruin.

The skills crisis: The glass screen generation

Perhaps the most consequential failure lies in the handling of youth. We talked endlessly about a demographic dividend but invested little in the mechanisms needed to empower it.

Policy focused on quantity: buildings, enrolment numbers, and certificates. Quality, relevance, and competence became afterthoughts. The result is a system that produces hundreds of thousands of graduates in disciplines poorly aligned with an economy that urgently needs technicians, skilled operators, and mid-level managers.

This mismatch has produced a full-blown skills crisis. Bangladesh now has a Glass Screen generation: around 75 percent of households own a smartphone, yet fewer than 5 percent own a computer. Young people are equipped to consume content and aspirations, but not to produce high-value work.

For over a decade, the celebrated “demographic dividend” and the promise of prosperity with every university degree have failed to materialise. By 2024, the figures were stark. Youth unemployment among those aged 15 to 24 stood at 11.46 percent. The rate for university graduates was even higher, at 13.11 percent. Estimates suggested that one in three graduates remained jobless for up to two years.

Additionally, nearly 40 percent of Bangladeshi youth fell into the “not in education, employment, or training” category, with significantly higher rates for females. Education has thus become a symbol of exclusion. It has created a paradox in which the more educated a person is, the more likely they are to be unemployed than illiterate labourers.

This systemic grievance was fuelled by a labour market in which degrees have lost currency and skills training lacks respect. The frustration was visibly expressed in the uprising of July 2024.

The grey wave: Ageing without a safety net

While public attention remains fixated on youth, a quieter crisis looms. Bangladesh is ageing rapidly. By 2050, the country will have an estimated 44 million elderly citizens.

Unlike wealthier countries, Bangladesh faces the prospect of ageing before achieving broad prosperity. The traditional family safety net, in which children cared for ageing parents, is fraying as households shrink and migration pulls younger members away.

The burden of this transition falls disproportionately on women. In zero-margin households, women already manage starvation budgets. The addition of elder care, especially for chronic conditions such as diabetes or heart disease, threatens to dissolve household stability altogether. Medical expenses are already the leading cause of financial insolvency. Without pensions or state-supported care, the Grey Wave risks deepening fragility across the working class.

Bangladesh has moved from villages to cities, but in a lopsided way centred overwhelmingly on Dhaka. File Photo: Anisur Rahman

To do or not to do

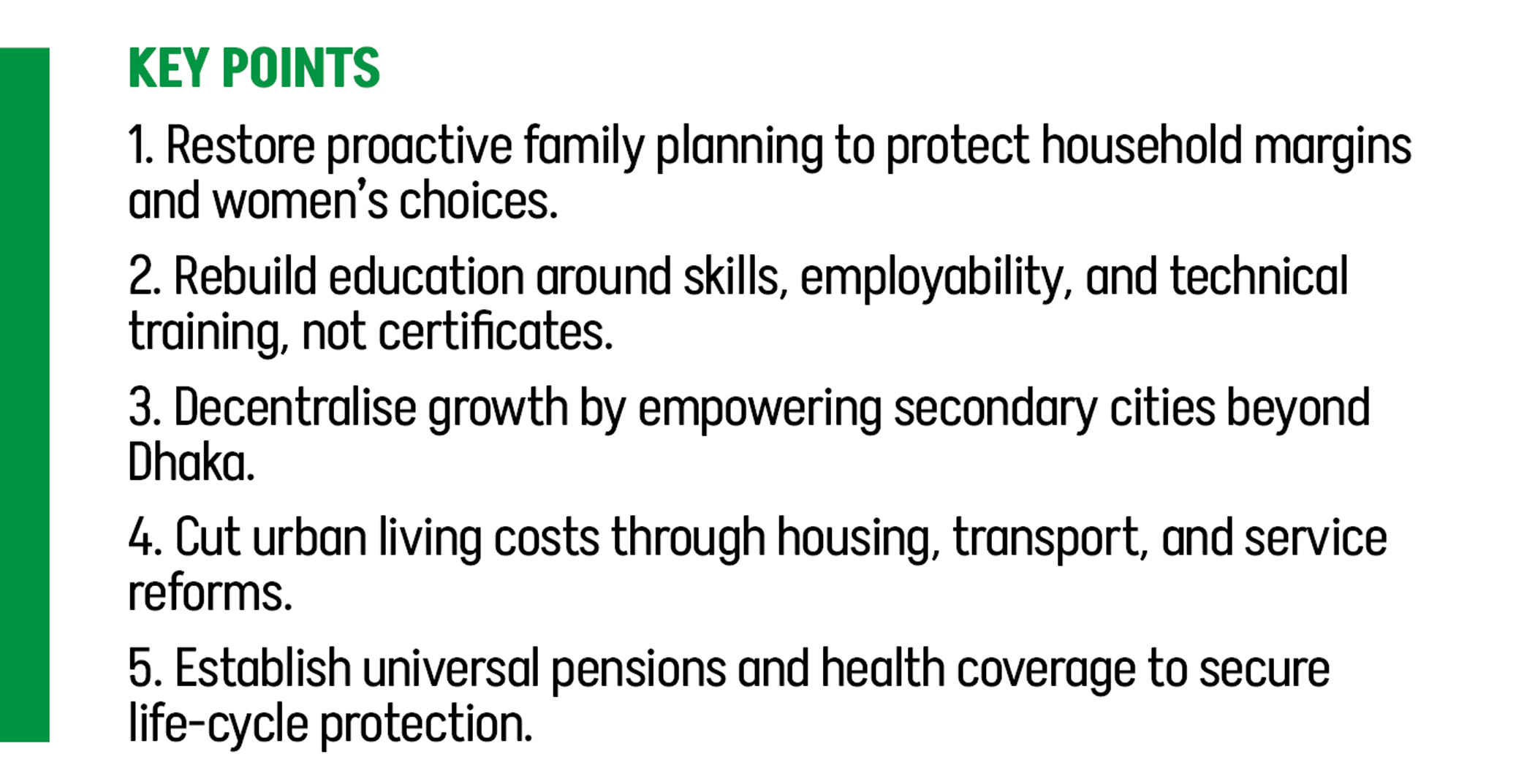

Bangladesh is not an exception here; it is an early warning of what happens when growth outpaces protection in the Global South. The momentum of inevitable progress appears to be fading. Markets alone cannot resolve the tensions of stalling fertility decline, chaotic urbanisation, frustrated youth, and a soon-to-be ageing population. What is required is serious recalibration—a new arrangement that moves beyond the project-based models of the past.

This begins with a redefinition of human capital. The bureaucratisation of education needs to be reversed through a rigorous overhaul of the National University system and a decisive effort to de-stigmatise vocational and technical training. The goal must shift from enrolment to employability, turning students into producers rather than credential holders.

Such a shift in skills must be matched by spatial rebalancing. Dhaka cannot remain the country’s sole economic engine. Real political decentralisation requires granting fiscal and administrative power to secondary cities if they are to function as independent growth centres. Urban planning must go beyond contracts and concrete and move towards reducing the cost of living for the poor.

Crucially, universal social protection must underpin these structural changes. Bangladesh needs to move from temporary relief to permanent, life-cycle security through pensions and health coverage. A nation cannot be resilient when 74 percent of healthcare is paid out of pocket, forcing families to choose between medicine and food.

File Visual: Shaikh Sultana Jahan Badhon

What Bangladesh is facing is not a crisis of numbers, but a crisis of margins. Our demographic window is narrowing, but the true danger is not an explosion. It is quiet calcification. The path the country is on will not collapse dramatically; it is hardening in slow motion. If drift continues, inequality will become structural—a permanent state of friction in which an underemployed youth population coexists with a destitute elderly class, neither able to lift the other. Avoiding this outcome will require acting with foresight, clarity, and resolve. Solutions are not unknown. However, the fatal danger lies in postponing them.

As a new year begins and the political calendar stands to open onto a new chapter, can we transcend declarative optimism and find the renewal of purpose and collective action that can drive the turning point the nation needs and deserves? We can, and we must.

Hossain Zillur Rahman is the Executive Chairman of the Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) and a former Adviser to the Caretaker Government

Send your articles for Slow Reads to [email protected]. Check out our submission guidelines for details.