Much has come and gone in Britain’s industrial history.

The cotton mills of Manchester, the coal mines up and down the country, and the shipyards that turned out more vessels than any other nation. But there is one industry this country has always been able to rely on: salt.

For hundreds of years, since long before the Industrial Revolution, Britain has produced all the salt it needed for domestic consumption. Indeed, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, this country was the world’s biggest salt exporter, sending tonnes of this vital chemical around the Empire, using it as a tool of power.

While it’s tempting to dismiss salt as something very humdrum – a substance we sprinkle on our fish and chips – it remains the bedrock for much of the chemicals sector. Salt, or rather the chemicals derived from it, is there in 90% of all pharmaceuticals. It is there in the formulas we use to purify our water and make plastics, explosives and materials with. Without salt, much of the physical economy would simply collapse – and that’s before you even get to its importance for keeping us all fed and healthy.

Share

UK chemical sector in crisis

And since Roman times, Britain has been able to depend on a more or less reliable supply of salt from an enormous slab of halite – rock salt – under the ground in Cheshire. Not every country has plentiful salt in its geology, but Britain does – thanks to an ancient sea that once sat beneath this country.

These days we produce nearly 3 million tonnes of salt – a lot less, admittedly, than we once did, but enough to satisfy national demand for everything from the salt in our salt cellars to the sodium chloride needed for pharmaceuticals. It gets pumped up from under the ground in Cheshire in the form of brine, and then sent for processing at two plants – one run by Tata Chemicals Europe and the other by Inovyn, part of Jim Ratcliffe’s INEOS. They take the brine, evaporate the water and then send the salt off to be packaged elsewhere (some even gets exported to Europe).

Relying on imports for the first time in modern history

All of which brings us to our big news. Inovyn, which produces about 50% of Britain’s salt, has told Sky News that without government intervention, it may have to shut down its salt plant in Runcorn. That would mean the UK becoming dependent on imported salt for the first time in modern history.

“Without a plant like this, we’d have to import,” says Tom Crotty, group director of chemicals at INEOS. “And the problem with importing salt is twofold. One, salt is a very corrosive material and that makes imports very, very difficult. And two, it’s a relatively low-value product. So the cost of the movement dramatically impacts the final price of the product.

“So you will find then you’ve got a situation where the UK, for example, the food industry is buying imported salt at a much higher price, which makes that uncompetitive. Against other products that it’s got to compete with. So it’s a complex supply chain issue.”

A deeper crisis facing the sector

But the potential end of British “salt independence” is just one element of a deeper crisis facing the chemicals sector. For decades, this was one of the most important slices of economic activity in the country. Many of the great early advances in industrial chemicals, including the invention of various plastics, the refining of key ingredients like ethylene and the creation of new materials like perspex happened in the UK. And since the chemicals sector is invariably at the very beginning of most manufacturing supply chains, it is of outsized importance when it comes to questions of national economic security.

For instance, the production of food in this country depends, among other things, on the use of fertilisers, chief among them nitrogen-based fertilisers. These fertilisers are typically made from natural gas, which is converted into ammonia via a technique known as the Haber-Bosch process. The UK was among the first countries in the world outside of Germany to make ammonia in this way, in the years after the First World War, at a site in Billingham at Teesside.

A critical area where Britain cannot provide

However, this plant, run latterly by American group CF Fertilisers, was shuttered in 2023 and has now been closed altogether. Britain now depends on imported ammonia for all its fertilisers. In other words, for all the talk about food security, this is a critical area where Britain cannot provide for its own means.

A couple of years earlier, Inovyn shut down its sulphuric acid plant in Runcorn. That might sound a little obscure, but this is another one of those critical ingredients you need to make all sorts of other important products. That comes into sharp focus when you note that the defence group recently said it intended to expand domestic production of explosives, to improve Britain’s national security.

For there is no making explosives without the nitrogen-based chemicals derived from ammonia and sulphuric acid. And Britain has just shut down the last plants making those ingredients in this country.

11 major shutdowns

According to Sky News research, in the last 10 years, 11 major chemicals plants have been shut down, many of them producing these key “foundational” chemicals which are needed for a host of other critical processes in this country. What’s striking is that many of these closures haven’t even been reported.

For instance, last year, Tata Chemicals Europe shut its soda ash plant in Lostock, after 150 years of near-continuous manufacturing. The decision means that now, for the first time in history, Britain is no longer making this critical chemical, sodium carbonate, needed for the manufacture of glass, paper and countless other products. The closure is doubly symbolic since soda ash was arguably one of the very first commodity chemicals made in the UK, in the very earliest years of the Industrial Revolution. Yet up until now, this plant’s demise hasn’t even been reported nationally.

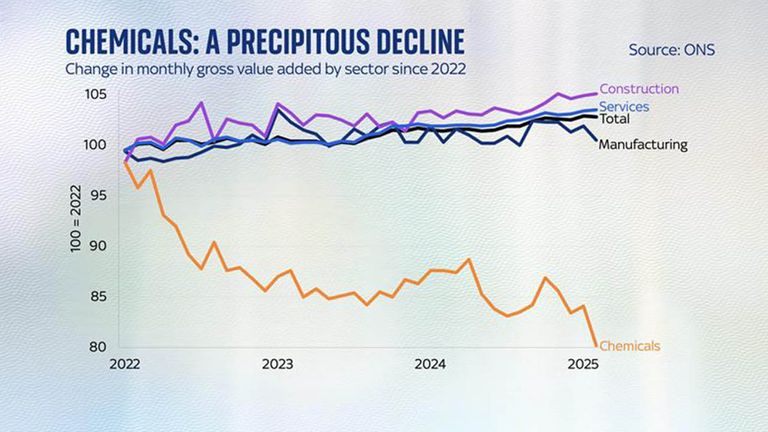

An unprecedented collapse

The recent collapse in chemicals sector output in recent years – down by 20% in the past three years alone – is entirely unprecedented outside of world wars. It is, in large part, a consequence of the rise in UK industrial energy prices. Since most industrial chemical production is highly energy-intensive, it is now far cheaper to carry out these reactions in other countries. Much of Europe’s production of commodity chemicals and fertilisers has shifted to China and the US since the Ukraine war pushed up gas prices.

Sharon Todd, head of SCI, a charity focused on industrial chemistry, says: “The slightly crazy thing about the whole situation is the market has continued to grow. So this is not a market in decline. This is a $6trn (£4.5trn) market globally. It’s huge. And so it’s continued to advance as new products and processes have come to market, but the UK has declined in that space.”

Image:

INEOS Grangemouth

Up until recently, the government had resisted pressure to help out the sector, but that changed in December when it stepped in with a grant to support INEOS’s ethylene cracker at Grangemouth. Had the cracker shut, that would have resulted in the end of one of the very last major chemicals branches still operating in the UK.

Sticking plaster solutions

However, that move is seen in the industry as more of a sticking plaster solution than a thorough response to a crisis facing the entire industry, much of which comes back to sky-high energy costs and extra carbon taxes, which affect most of the activities done by UK firms. Added to this is the fact that much of Britain’s chemicals infrastructure is extremely aged, some of it dating back a century or so – including some of the vessels used by Inovyn to make salt at Runcorn.

Image:

Inovyn, Runcorn

Much of that hardware was installed in the early and mid-20th century by ICI, the British chemicals giant. When it collapsed at the turn of the millennium, it sold off many of its units piecemeal. Those units still comprise much of the remaining chemicals infrastructure in the country, but since they are now relatively small and atomised, their gradual shutdown has barely been noticed.

Image:

Wilton, North Yorkshire

However, if you visit what used to be the heart of Britain’s petrochemicals industry, the vast Wilton Site on the south of the River Tees, you see viscerally how little is left of this once-world-beating location. A few months ago, Sabic, the Saudi petrochemicals group, shut down the ethylene cracker there. It is now a husk, soon to be dismantled. Very few units are left running at Wilton.

Among the few remaining is the aniline plant run by Huntsman International, an American firm once famed for making the containers for McDonald’s Big Macs but now an expert in making composites used in aerospace. We spent a day up there recently with chief executive Peter Huntsman. He masterminded buying the assets from ICI decades ago. Now this aniline plant is among the last remaining reminders of what used to be a vast, hulking site.

‘It’s terribly depressing’

“It’s terribly depressing,” he says, as we walk by the shadow of the Sabic ethylene cracker. “Because the raw materials are still here, heaven knows the workers are still here. This had one of the most competent, capable, hardest-working workforces anywhere in the world. The productivity, the reliability, the safety that came out of this site was phenomenal. And now this is just a skeletal remains.

“And it’s not that we’ve stopped using the product. We’re using more of this product today than we ever have in the history of the world. And the raw materials to make it are right offshore. It’s right under our feet right now. You could have this industry back if the government wanted. Now that’s not a nice thing for an American to come over here and say, but this is a global industry.

“Europe is fast becoming a geriatric Disneyland where a lot of old people will be coming, visiting castles, spending some money and leaving. But this,” Mr Huntsman points at the chimneys at Wilton, “is what makes things. This is where electricians and pipe fitters and welders and drivers and hauliers [work]. This is what makes your middle income.

“Nobody sees the raw materials, very few people see the finished product, but these are the essential building blocks of modern society. Without it, you’re just a service industry, just a service economy.”

But since many of the industry’s activities are indeed very carbon-intensive, the closure of these plants will actually help Britain get another step closer to its goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Ed Miliband and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero have made clear that they stand by the government’s plan. However, Ms Todd warned that without a change, more plants would close.

“Our net zero strategy also needs another rethink and a remoulding so that we can grow industry,” she says. “We can move towards net zero and we can create jobs and rebuild some of those communities that were at the heart of what I saw when I started in the sector.

“We’ve lost a huge amount of capability. Products like soda ash, which are fundamental for so many other processes. Products such as ethylene, which we know is under threat… We’ve lost ammonia out of the UK, a core fertiliser, but also important in the energetics market. We’ve lost sulphuric acid and nitric acid, which again are important for defence.

“These are core building blocks. I would say we’ve probably lost 90% of the core building blocks that we need, and Ethylene is almost the last hope.”

Steve Elliott, chief executive of the Chemicals Industries Association, said: “The government’s own Industrial Strategy acknowledges chemicals as a key foundational sector. Well, enough of the rhetoric and more urgency please on meaningful energy and carbon policy and funding to enable us to survive, compete and deliver for the country.

“Otherwise, we’ll see further deindustrialisation through decarbonisation in 2026, with serious implications for our critical national infrastructure, growth sector supply chains and net zero delivery.”

The end of salt manufacturing in a key plant, leaving the UK dependent on imports for the first time in history, would undoubtedly be seen as a watershed moment – a final nail in the coffin for an industry which was once the pride of the economy.