Gathering for their first meeting of 2026, the board of health for Public Health Sudbury heard details of a northern-specific fungal infection, blastomycosis, which killed five people in Constance Lake First Nation in 2021 and could become an issue here on Sudbury

As the board of health for Public Health Sudbury and Districts (PHSD) gathered for their first meeting of 2026 it was the details of a northern-specific fungal infection, one that killed five people in 2021 in Constance Lake First Nation, that formed the majority of the agenda.

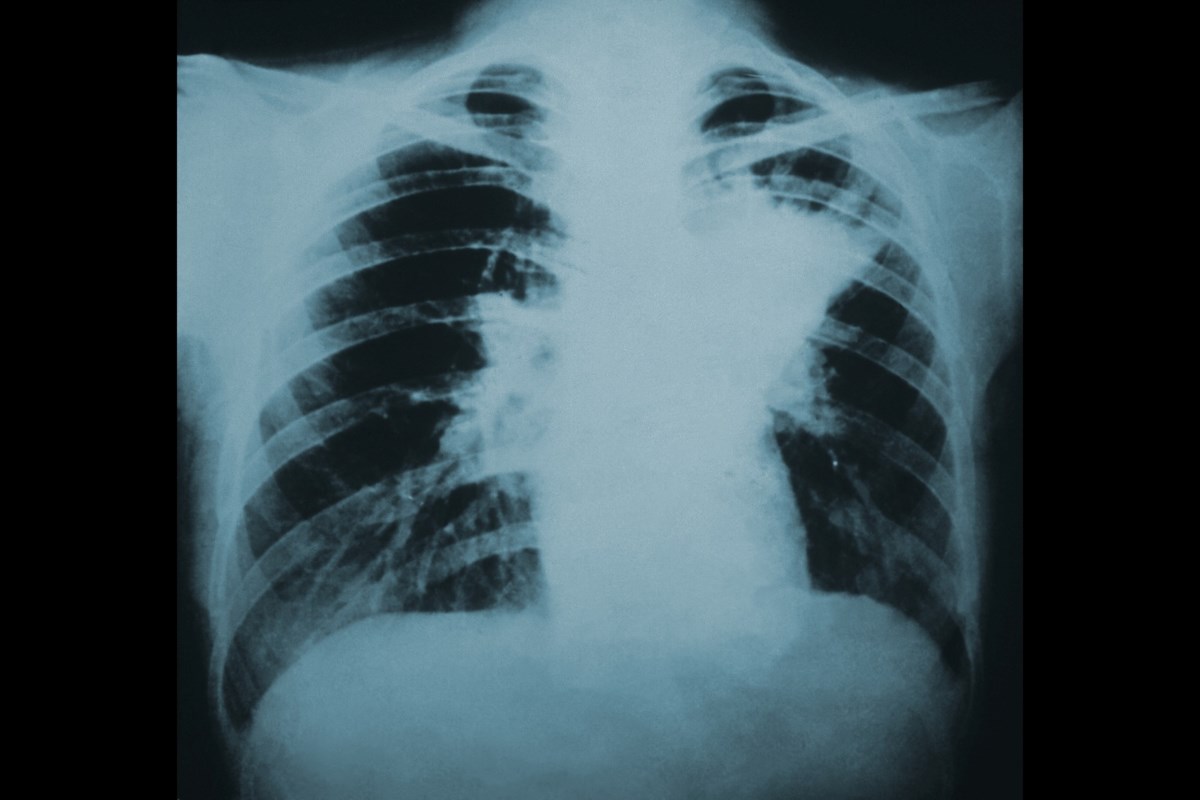

Blastomycosis is a lung infection caused by the fungus blastomyces dermatitidis and though rare, the fungus has become an almost household name after a 2025 inquest into the deaths of Luke Moore, 43, Lorraine Shagansh, 47, Lizzie Sutherland, 47, Mark Ferris, 67, Douglas Taylor, 60.

Held over four weeks, from Oct. 15 to Nov. 19, the inquest included 79 recommendations for the parties involved, and it was on these recommendations that the recently-appointed associate medical officer of health, Dr. Emily Groot, centred her presentation. Groot was at one time a regional supervising coroner for Northeastern Ontario and is also the program director with the Public Health and Preventive Medicine Residency program at NOSM University.

The recommendations circled the challenges that arose in treating those affected, “challenges of communication, collaboration, timeliness and information sharing that impacted the community and their ability to access care,” said Groot.

It’s what she referred to as “jurisdictional neglect,” meaning one organization points a patient to another, citing the region-based limitations, which ends in a person accessing several points of health care, but never finding any.

After a moment of silence for the dead, she told the board that while the Constance Lake area, which is located about 138 km west of Kapuskasing off Highway 11, was not in their jurisdiction, the fungus is a Northern Ontario problem. “It doesn’t technically apply to us, because we are not part of that region, but nonetheless, we want to be proactive and learn from the experiences of others to make sure something like that could never happen here,” she said.

Groot said the fungus is “endemic in the soil in Northern Ontario, especially Northwestern Ontario,” meaning (of a plant or animal) that it is native to the area and restricted to a certain place.

Preferring acidic soil near waterways, which accurately describes the ecosystems of Northern Ontario, the fungus can spread to anyone who goes outdoors, said Groot. It grows most commonly in moist soil and decomposing wood and leaves and if an area like this is disturbed, tiny fungal spores may be released into the air which can lead to infection if inhaled.

In fact, it’s almost impossible to link outbreaks to a specific event or exposure, she told the board. “Even if we tested the soil, we might find the fungus but we don’t know if it’s connected to someone’s illness or not.”

That, and most immune systems easily handle the infection, which usually presents similarly to pneumonia, she said. According to Public Health Ontario, symptoms may develop between three weeks to three months following exposure and commonly include fever, cough, extreme fatigue, night sweats, muscle aches, and joint pain; however, about 50 per cent of those infected will not become ill.

“In Ontario, we see 50 to 130 cases per year of this infection, so it’s not very common,” she said. But sadly, that was a factor in the Constance Lake outbreak. “Because when things aren’t common, they’re harder to pick up.”

She said in the Public Health Sudbury and District region, there were three cases last year and five cases the year before. These cases were not fatal.

What the report did not state, and which apparently remains a mystery, is why Constance Lake experienced a cluster of 40 blastomycosis infections in the fall of 2021, a case count that represents nearly the provincial average number of cases for an entire year, in a single small community.

According to Public Health Ontario’s information, there were 126 cases across the province in 2023, a rate of 0.8 people per 100,000, and of those cases, 11 people died.

During Groot’s presentation, the board learned that blastomycosis begins when someone inhales the spores of the fungus; it does not pass from person-to-person or animal -to-person.

But the problem is, it’s not something that most doctors will think to diagnose, said Groot. It’s not found in Southern Ontario, and doctors are told to look for what could be a common condition, not a rare one.

Groot noted a quote by Dr. Thoedore Woodward, which is taught in medical school: “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.”

But this time, “it was zebras,” she said.

Groot told the board that as the patient usually presents with symptoms similar to a bacterial infection like pneumonia and are misdiagnosed, treated with an anti-biotic when an anti-fungal should be administered.

It was the delay in recognizing the fungus in Constance Lake that caused the deaths of the five subjects of the inquest, as well as affecting more than 40 others with serious illness, said Groot.

And it’s because inquest makes recommendations to prevent similar deaths, there is a direct overlap with the role of Public Health, she said, “to eliminate preventative death.”

For her, the relevant recommendations include numbers one, four, 24/27/28, 31 and 33/34/35. You can find these as well as the other recommendations here.

For the board, the recommendations she cited included workforce inclusion and ongoing cultural learning, as well as a commitment to Joyce’s Principle, named for Joyce Echaquan, who died in 2020, at a hospital in Lanaudière, Que. The principle seeks to guarantee to all Indigenous people the right of equitable access, without any discrimination, to all social and health services.

There should also be a focus on improving access to health care, specifically in Northern and Indigenous communities, as well as collaboration with those communities to ensure they receive a high standard of care. In addition to that, better data is required for tracking and research, said Groot, but in keeping with a goal of Indigenous sovereignty, “it should be collected in a culturally safe way, with ownership, control, access and possession in the hands of Indigenous people.”

You can find more information on blastomycosis, including ways to protect yourself, on the PHSD website, found here.

Jenny Lamothe is a reporter with Sudbury.com, covering vulnerable and marginalized populations, as well as housing issues and the justice system.