The 1970s are usually remembered through a handful of towering titles, but that shorthand can obscure just how deep and adventurous the decade really was. It was a period when filmmakers were granted unusual freedom, when commercial expectations loosened just enough to allow ambiguity, moral risk, and emotional roughness to thrive.

With this in mind, this list looks at some lesser-known movies from that decade that have aged remarkably. Sure, the titles below aren’t that obscure, but they don’t really need to be. Instead, they’re the kind of films that even cinephiles might not have gotten around to seeing yet, without any negative connotation or redemption arc necessary. All are worth checking out, and all will leave any viewer with a renewed appreciation for ’70s cinema.

10

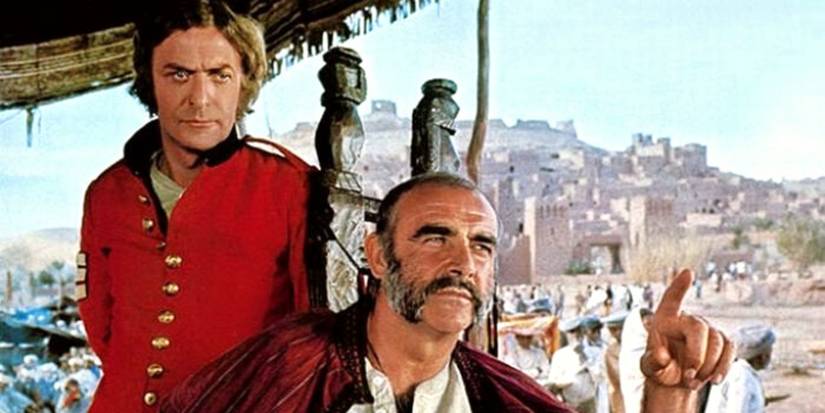

‘The Man Who Would Be King’ (1975)

Image via Columbia Pictures

“Whatever you may think, and however you may feel, I’m a king and you’re a subject!” The Man Who Would Be King is an old-fashioned adventure film with a surprisingly modern moral backbone. It’s about two former British soldiers (played by Sean Connery and Michael Caine) who venture into a remote region of Afghanistan, hoping to exploit local tribes and crown one of themselves as a god-king. What begins as a roguish escapade gradually transforms into a meditation on arrogance, colonial fantasy, and self-deception.

From here, the movie unfolds with the confidence of a classic yarn, but its emotional arc is far darker than it first appears. Indeed, at times it’s an outright cautionary tale. While the protagonists may be charming and clever, their belief in their superiority ultimately proves fatal. Taken together, The Man Who Would Be King makes for an entertaining take-down of hubris, as well as a not-so-thinly veiled critique of empire.

9

‘The Last Detail’ (1973)

Jack Nicholson in The Last Detail – 1973Image via Columbia Pictures

“I am the shore patrol!” The Last Detail is a road movie stripped of romanticism and filled with bitter humor. Jack Nicholson and Otis Young lead the cast as a pair of Navy lifers tasked with escorting a young sailor (Randy Quaid) to prison for a minor offense. Along the way, they decide to give him a taste of freedom before his sentence begins. The plot is episodic, unfolding through bars, train rides, and fleeting moments of connection.

The script (by Chinatown‘s Robert Towne) is brilliant, and the leads rise to the occasion with layered, enjoyable performances, Nicholson most of all. Their characters are crude, funny, angry, and deeply constrained by the systems they serve, and they undergo genuine development throughout the story. Through them, director Hal Ashby captures a specifically 1970s disillusionment, where authority is arbitrary, and compassion feels like a small rebellion.

8

‘Five Easy Pieces’ (1970)

Bobby looks in the mirror in Five Easy PiecesImage via Columbia Pictures

“No substitutions!” Jack Nicholson strikes again. He delivers one of his very best performances in Five Easy Pieces as Bobby Dupea, a gifted pianist who has rejected his privileged background and drifts through blue-collar life, incapable of committing to anything or anyone. Rather than playing his instrument, Bobby whiles away his time working on an oil field. When he reluctantly reconnects with his family, long-suppressed resentment and insecurity rise to the surface.

The narrative resists traditional structure, mirroring Bobby’s emotional aimlessness. Instead of the expected three-act drama, we get a portrait of modern alienation. Five Easy Pieces is a study in masculinity, delving deep into the fractured, defensive psyche of its protagonists, a man undone by class guilt and emotional cowardice. The movie feels as contemporary now as it did in 1970 because its central question, what to do with freedom when you don’t know who you are, has never gone away.

7

‘The Parallax View’ (1974)

“You are what you do.” The Parallax View is paranoia cinema at its most controlled and unnerving, perhaps Alan J. Pakula’s most effective thriller. It centers on a journalist (Warren Beatty) investigating a political assassination, who uncovers a shadowy corporation linked to multiple acts of violence. Despite the danger, he digs deeper, only for the conspiracies to grow more abstract and more terrifying the more he learns.

The movie itself is a work of deception and trickery, offering the viewer many clues but few certainties. The Parallax View is most famous now for its montage, where words like “LOVE” and “MOTHER” are juxtaposed with images of people like Nixon, Lee Harvey Oswald, Thor, and Hitler. The sequence is chilling and well done, very much speaking to the confusion and cynicism of post-Kennedy, post-Watergate America. Its themes of misinformation and eroded trust still resonate.

6

‘Don’t Look Now’ (1973)

Donald Sutherland as John Baxter holding a child in a red coat while screaming in Don’t Look NowImage via British Lion Film Corporation

“I keep seeing red.” Don’t Look Now is one of the greatest horrors of the ’70s, and yet many horror fans might still not have seen it. It features Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as a married couple in Venice struggling to process the death of their child. There, they begin encountering strange, possibly psychic occurrences. However, the supernatural elements feel secondary to the characters’ inability to move forward.

Fundamentally, this movie is about emotions, particularly grief. Director Nicolas Roeg’s fragmented editing mimics the way trauma collapses time, allowing past and present to bleed into one another; memory, coincidence, delusion, and dread fuse. The film’s final revelation is devastating not just because it’s shocking, but because it completes an emotional pattern the film has been quietly building all along. Initially dismissed as overly artsy, Don’t Look Now has been hugely influential in the decades since its release, inspiring everyone from Ari Aster to Steven Soderbergh.

5

‘The Taking of Pelham One Two Three’ (1974)

Image via United Artists

“Gesundheit.” The remake is mediocre, but the original The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is a razor-sharp procedural thriller that still holds up. The story centers on a group of criminals (played by Robert Shaw, Martin Balsam, Héctor Elizondo, and Earl Hindman) who hijack a New York subway train and demand a ransom, while a transit police officer (Walter Matthau) works to negotiate and outmaneuver them. It’s brisk and precise, built around logistics, timing, and urban infrastructure. It’s tense but not flashy, cynical but not nihilistic.

In an age of overproduced thrillers, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three feels refreshingly grounded. The criminals are methodical rather than theatrical, which makes them more unsettling. Likewise, the film’s humor is dry and character-based, never undercutting the stakes. The movie made an impression on a rising generation of filmmakers. The color-coded character names in Reservoir Dogs, for example, are an homage to Pelham.

4

‘The Last Wave’ (1977)

Image via United Artists

“What are dreams?” The Last Wave is an early film by Peter Weir (Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Truman Show), and it’s one of the strangest and most quietly unsettling films of the 1970s. It focuses on a Sydney lawyer (Richard Chamberlain) who becomes involved in the defense of several Indigenous men accused of murder. While the case unfolds, he begins experiencing vivid, prophetic dreams tied to Aboriginal mythology, environmental catastrophe, and an impending sense of doom.

The plot moves cautiously, allowing the legal drama and the supernatural elements to bleed into one another rather than collide outright. Weir never over-explains the symbolism, trusting atmosphere, sound, and imagery to do the work. Rain becomes oppressive, water takes on mythic weight, and modern urban life feels fragile in the face of older, deeper truths. Almost 50 years later, this vision of cultural disconnection and environmental imbalance feels strikingly contemporary.

3

‘The Friends of Eddie Coyle’ (1973)

Robert Mitchum as Eddie Coyle sitting in the back of a car in ‘The Friends of Eddie Coyle’Image via Paramount Pictures

“Friends come and go, but enemies accumulate.” The Friends of Eddie Coyle follows a low-level gunrunner (Robert Mitchum) facing prison who considers informing on his associates to save himself. The title is a joke: in Eddie’s world, there are no friends. In a lesser director’s hands, this could have been a stereotypical, action-driven crime flick, but Peter Yates instead goes for immersive realism. He tells the story through conversations rather than action, emphasizing routine, loyalty, and quiet desperation.

As a result, The Friends of Eddie Coyle presents crime as monotonous and transactional, stripped of glamour or mythology. Everyone is compromised, and survival requires betrayal rather than bravery. The film understands criminal ecosystems as bureaucratic structures, governed by pragmatism rather than honor. Mitchum carries much of it single-handedly, delivering a towering performance as the tough, proud, weary Eddie. The result is a gritty but perceptive character study.

2

‘Days of Heaven’ (1978)

Richard Gere and Brooke Adams in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978)Image via Paramount Pictures

“I didn’t know there was so much beauty in the world.” Terrence Malick burst onto the scene with the phenomenal Badlands, then followed it up with the more lyrical, poetic Days of Heaven. It stars Richard Gere as a laborer who travels with his lover (Brooke Adams) and sister (Linda Manz) to work on a wealthy farmer’s (Sam Shepard) land, where a love triangle slowly takes shape. The premise is simple, almost skeletal, but the emotional weight is immense.

The visuals are a key part of the tone and mood. Malick uses light, landscape, and silence to convey longing, jealousy, and inevitability. Dialogue is sparse, allowing the imagery to carry the meaning. The cinematography is some of the most gorgeous of any ’70s movies (it won that year’s Oscar), paying clear homage to Murnau’s City Girl. It gets inventive, too, like in the sequence where they created a “locust swarm” by pouring peanut shells from helicopters and then playing the footage backward.

1

‘Sorcerer’ (1977)

A man climbing a rickety bridge during a thunderstorm with his truck behind him in 1977’s SorcererImage via Paramount Pictures

“We’re all gonna die.” With Sorcerer, William Friedkin remade The Wages of Fear, turning it into an even more relentless, existential thriller about men trapped by their pasts. In it, four criminals from different parts of the world (played by Roy Scheider, Bruno Cremer, Francisco Rabal, and Amidou) take on a suicidal job transporting volatile explosives through treacherous terrain.

The movie mines this premise for maximum tension. Every movement feels dangerous, every success temporary. Friedkin treats suspense as physical and moral pressure, emphasizing exhaustion and fear rather than heroics. It culminates in a nail-biting sequence where the characters attempt to cross a rickety rope bridge, every swing and creak potentially spelling disaster. This approach might have been too much for audiences in 1977: Sorcerer was a box office bomb. However, for the right kind of viewer, it’s a grim, gritty masterpiece, a piercing statement on fate and labor.