Russian researchers are testing a new plasma propulsion system that may accelerate future missions to Mars, reducing travel time from months to just one or two. The engine, developed by Rosatom’s Troitsk Institute, is now in ground-based trials and could be space-ready by 2030.

The system, which uses electromagnetic fields to accelerate hydrogen particles, represents a departure from conventional chemical propulsion. If it performs as projected, it may significantly shift interplanetary mission planning across both civil and defense sectors.

Russia’s development effort coincides with a growing global push to advance electric propulsion systems for deep space. The potential to shorten mission durations while reducing fuel mass has made plasma-based engines a priority for future exploration architectures.

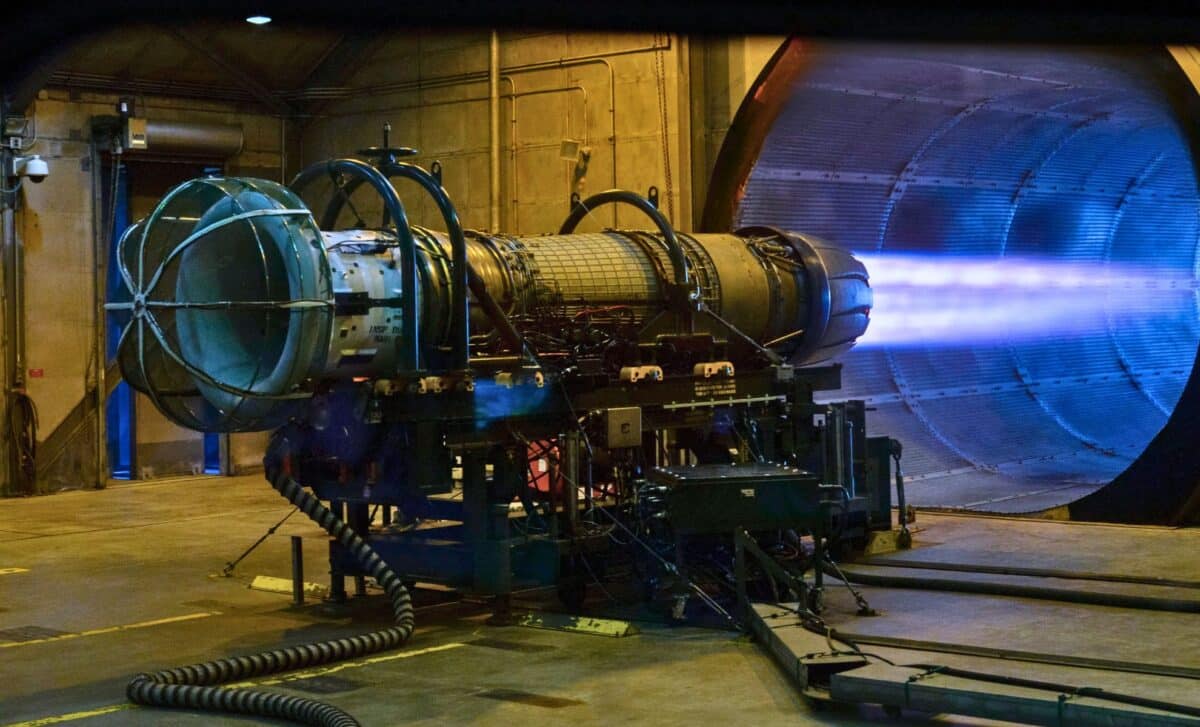

Ground Tests Target Deep-Space Readiness

The prototype is undergoing tests inside a 14-meter vacuum chamber designed to simulate space conditions. Operating at 300 kilowatts, the engine runs in a pulse-periodic mode and has already demonstrated a service life of 2,400 hours, as outlined in a technical breakdown by Izvestia. That duration is sufficient for a complete Mars mission, including acceleration and deceleration phases.

Image Credit: IZVESTIA/Sergey Lantyukhov.

Image Credit: IZVESTIA/Sergey Lantyukhov.

The propulsion system accelerates charged hydrogen particles—protons and electrons—to speeds of up to 100 kilometers per second, confirmed Alexei Voronov, First Deputy Director for Science at the institute. That velocity far exceeds current chemical rockets, which typically max out around 4.5 kilometers per second.

The unit is not intended for launch from Earth’s surface. Instead, chemical rockets would deliver the spacecraft into low-Earth orbit, where the plasma engine would activate to provide continuous propulsion through deep space. Officials added that it may also function as a space tug, transferring cargo or modules between planetary orbits.

Hydrogen Fuel and Nuclear Power Enable Efficiency

The engine relies on hydrogen fuel and an onboard nuclear reactor to generate sustained power. Egor Biriulin, a junior researcher involved in the project, said the light atomic weight of hydrogen enables faster acceleration with lower fuel consumption. Hydrogen’s abundance in the universe may also allow for future in-situ refueling strategies.

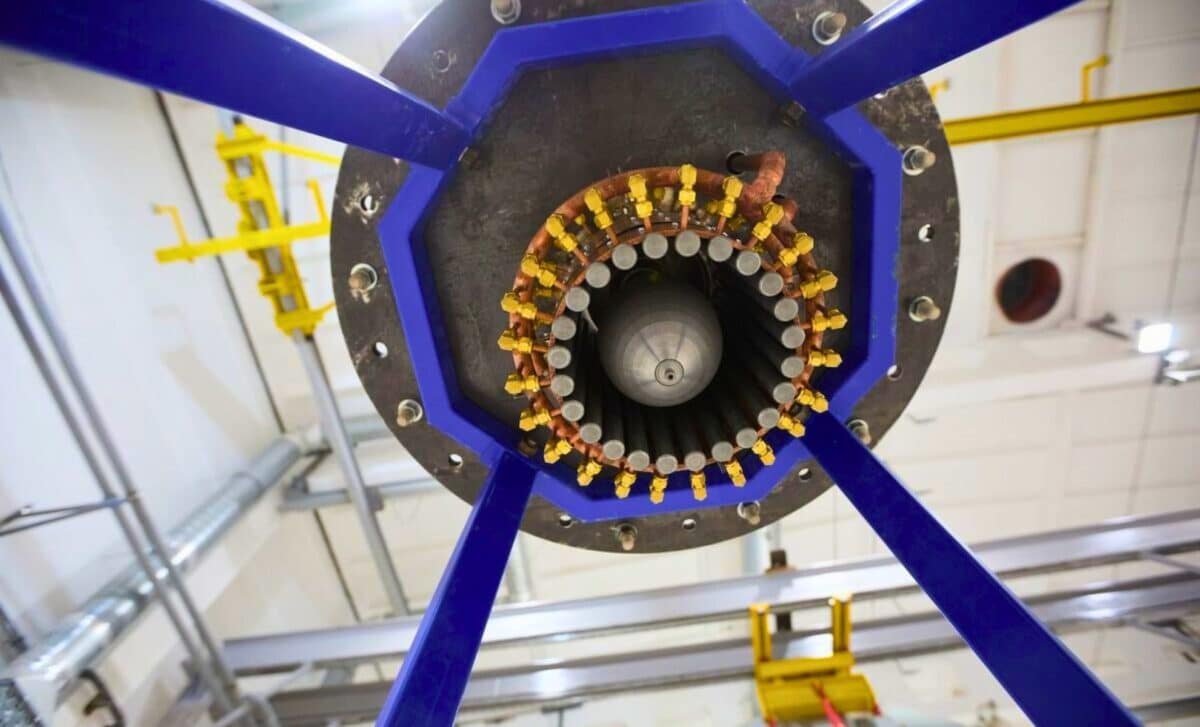

Image Credit: IZVESTIA/Sergey Lantyukhov.

Image Credit: IZVESTIA/Sergey Lantyukhov.

Biriulin also noted that the engine produces directional plasma motion using two high-voltage electrodes. Charged particles are passed between them, creating a magnetic field that expels plasma to generate thrust. This configuration avoids the need to heat plasma to extreme temperatures, limiting wear on components and enhancing energy efficiency.

The projected thrust is 6 newtons, the highest among current plasma propulsion prototypes, based on findings in Rosatom’s technical documentation. This force would require extended phases of acceleration and deceleration, suggesting that future spacecraft would be designed around slow, sustained propulsion rather than short, high-thrust burns.

Track Record in Plasma Thrusters

Plasma propulsion is already used in orbit, including by several satellites and missions launched over the past decade. Russian-built systems support OneWeb satellites and were integrated into NASA’s Psyche asteroid mission, which launched in 2023.

Image Credit: IZVESTIA/Sergey Lantyukhov.

Image Credit: IZVESTIA/Sergey Lantyukhov.

Current plasma thrusters typically operate at speeds between 30 and 50 kilometers per second. The new engine claims double that range, putting it well ahead of other systems under development in the United States, Europe, and China. No peer-reviewed performance data have been released, and the system has not yet been tested in space.

Russia’s developers emphasize the performance gap compared to conventional systems. “In traditional power units, the maximum velocity of matter flow is about 4.5 kilometers per second… In our engine, the working body is charged particles that are accelerated by an electromagnetic field,” Voronov told Izvestia.

Deployment Challenges and Regulatory Risks

Space-qualified nuclear-powered spacecraft are rare due to safety concerns and regulatory scrutiny. No reactor design has been released for the Rosatom system, and the handling of nuclear material during launch may require approval from international space agencies and watchdogs.

The integration of such a propulsion system into a crewed spacecraft would also demand significant redesigns. Thermal management, radiation shielding, and power distribution at sustained high output are areas where engineering challenges remain unresolved.

Despite its potential, the engine is still years away from deployment. Officials anticipate a flight-ready version by 2030, but timelines depend on successful testing, funding continuity, and external validation.