Astrophysicists from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) and the Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) have discovered the most complex sulfur-bearing molecule ever found in interstellar space. The molecule, 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-thione (C₆H₆S), was identified in the molecular cloud G+0.693–0.027, located near the center of the Milky Way, roughly 27,000 light-years from Earth. Their findings, combining high-precision lab spectroscopy and radio astronomy, were published in Nature Astronomy.

A Sulfur Molecule Like No Other

This newly detected molecule is unlike anything previously observed in space. C₆H₆S consists of a six-membered carbon ring with a single sulfur atom, forming a stable 13-atom compound. Its structure significantly surpasses the size and complexity of all other sulfur-containing molecules ever found in the interstellar medium, most of which had no more than six atoms.

The detection of C₆H₆S marks a critical shift in astrochemistry. It demonstrates that complex, ring-based sulfur compounds, long theorized to exist, do indeed form in space, even in cold, starless environments.

“This is the first unambiguous detection of a complex, ring-shaped sulfur-containing molecule in interstellar space and a crucial step toward understanding the chemical link between space and the building blocks of life,” says Mitsunori Araki, lead author of the study and scientist at MPE.

This finding also bridges a major gap in the chemical narrative of our solar system. Previously, such ring-shaped sulfur molecules had only been seen in meteorites or comets. The presence of a molecule with a similar structure in deep space suggests a shared chemical ancestry between interstellar clouds and the early solar system.

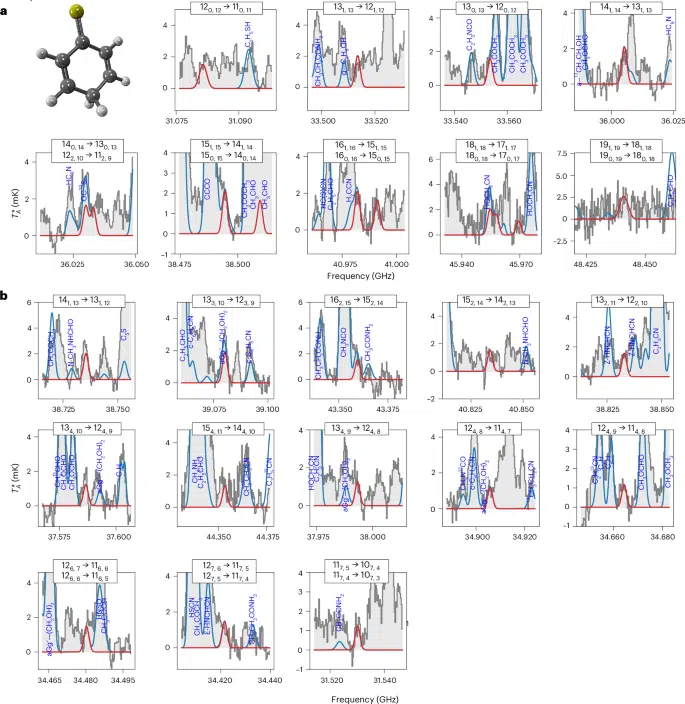

Lines of 2,5-CT detected towards the Galactic Centre molecular cloud G+0.693.

Lines of 2,5-CT detected towards the Galactic Centre molecular cloud G+0.693.

a, Pairs of Ka = 0 and 1 transitions that progressively converge with increasing frequency, ultimately coalescing into a doubly degenerate line. b, Ka > 1 transitions of 2,5-CT observed in the astronomical data that were also used to derive the LTE physical parameters of the molecule (see text; listed in Extended Data Table 2). The quantum numbers for each transition are shown in the upper part of each panel. The red lines depict the result of the best LTE fit to the 2,5-CT rotational transitions. The blue lines are the emission from all the molecules identified to date in the survey, including 2,5-CT, overlaid with the observed spectra (grey histograms and light grey shaded area). The three-dimensional structure of 2,5-CT is also shown (carbon atoms in grey, S atom in yellow and hydrogen atoms in white).

Credit:Nature Astronomy.

A Chemical Milestone

Published in Nature Astronomy, the study combines laboratory innovation with precise astronomical measurements. The team at MPE synthesized C₆H₆S by discharging 1,000 volts through thiophenol (C₆H₅SH), a strong-smelling sulfurous compound. This process created a plasma that allowed C₆H₆S to form under controlled conditions.

Using a self-developed laboratory spectrometer, the researchers captured the molecule’s unique radio fingerprint, an ultra-precise pattern of emissions recorded to seven significant digits. This radio signature was then matched to data from previous sky surveys conducted with the IRAM 30m and Yebes 40-meter radio telescopes in Spain. The perfect match confirmed that this molecule does, indeed, exist in the cosmic cloud G+0.693, 0.027, where new stars and planetary systems are just beginning to form.

The use of custom-built lab equipment proved essential. The team’s setup included a large vacuum chamber where the molecules were both created and measured. This one-two approach, laboratory synthesis followed by sky validation, sets a new benchmark for molecular astrophysics.

What This Means For the Search for Life

The discovery of C₆H₆S has profound implications for our understanding of how life’s chemical building blocks might emerge long before planets and even stars form. The cloud where the molecule was detected is still in a starless stage, making it a pristine site for studying early chemical evolution.

“Our results show that a 13-atom molecule structurally similar to those in comets already exists in a young, starless molecular cloud. This proves that the chemical groundwork for life begins long before stars form,” says Valerio Lattanzi, another researcher at MPE.

The fact that such a molecule could survive and be detected in such an environment strongly supports the idea that prebiotic chemistry, the formation of life-like molecules, begins in deep space, not just within solar systems.

Sulfur plays a vital biological role on Earth, particularly in proteins and enzymes, and the formation of complex sulfur compounds in space suggests that other planetary systems may have started with similar chemical advantages. This detection also raises expectations that many other undiscovered sulfur molecules may be present in interstellar clouds, quietly laying the groundwork for future biochemistry.