A new study led by Robb Calder at the University of Cambridge suggests that nearly all known sub-Neptune exoplanets, previously thought to be potential ocean-bearing “hycean worlds,” are far more likely to be composed of molten rock.

This shift is grounded in how scientists interpret the atmospheric data of distant planets, especially chemical markers like methane, carbon dioxide, and ammonia. Previous research, including the case of planet K2-18b, leaned on the absence of ammonia as evidence of liquid water oceans, since water is known to absorb ammonia. But Calder and his team argue that molten rock behaves similarly, and therefore the same observation could imply an entirely different planetary reality.

Are Sub-neptunes Hiding A Rocky Secret?

Sub-Neptunes, planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, are the most commonly discovered type of exoplanet. Yet, their exact nature has remained elusive, in part because our solar system offers no direct equivalent.

Understanding what these worlds are made of not only shapes the search for life but also helps refine our broader models of planetary formation and evolution. According to the paper, available on the arXiv preprint server, assumptions about sub-Neptunes being watery havens may have jumped too quickly to the most optimistic explanation, bypassing more geologically grounded alternatives.

The Problem of Planetary Degeneracy

At the heart of the debate is a concept known in astrophysics as degeneracy, a term used when one set of observations can be interpreted in multiple ways. This is particularly evident in atmospheric chemistry. In the case of K2-18b, researchers once celebrated its methane-rich, ammonia-poor atmosphere as the hallmark of a hycean planet, an exotic type of exoplanet with a thick hydrogen atmosphere overlying vast oceans.

K2-18b, a sub-Neptune exoplanet once considered a potential hycean world. Credit: NASA

K2-18b, a sub-Neptune exoplanet once considered a potential hycean world. Credit: NASA

As Robb Calder and his co-authors point out, however, molten rock can also dissolve ammonia, just like water can. This undermines the earlier claim that the absence of ammonia necessarily implies the presence of oceans. The ambiguity in the data, as reported by the research, means that many exoplanets previously identified as potentially habitable water worlds could instead be hot, barren magma worlds.

Measuring Planets Differently

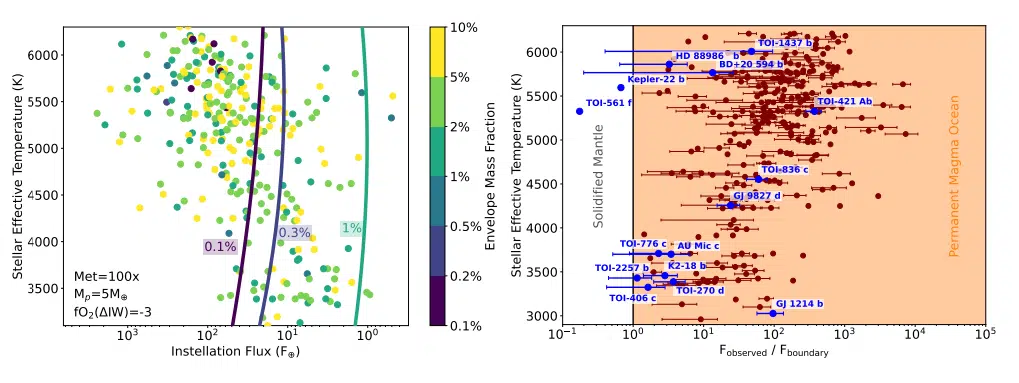

To put their theory to the test, the researchers introduced a new model called the Solidification Shoreline. This tool connects the instellation flux, the amount of energy a planet receives from its host star, with the star’s effective temperature. By plotting known exoplanets against this framework, they could estimate whether a planet was likely to have maintained a magma ocean since formation.

Figure: Left: Sub-Neptunes by stellar temperature and instellation flux, colored by envelope mass. Right: Most planets lie beyond the solidification boundary, in the permanent magma ocean zone. Credit: arXiv

Figure: Left: Sub-Neptunes by stellar temperature and instellation flux, colored by envelope mass. Right: Most planets lie beyond the solidification boundary, in the permanent magma ocean zone. Credit: arXiv

Using the PROTEUS model to simulate internal heat dynamics, Calder’s team found that 98% of sub-Neptune exoplanets fall above this shoreline. That suggests those planets receive enough stellar energy to keep their interiors hot and molten, rather than allowing them to cool into solid bodies. This finding provides a straightforward alternative to the more speculative hycean hypothesis, one grounded in planetary physics rather than the allure of habitability.

Magma-Driven Exoplanets, Not Ocean Worlds

For astrobiologists and exoplanet hunters, the implications are significant. The hycean world hypothesis had offered an enticing vision, planets that might host life in vast subsurface oceans, protected by thick atmospheres. As reported by the new study, that vision may have been premature. If the vast majority of sub-Neptunes are in fact lava worlds, then they are far less likely to support life as we know it.

While this conclusion may seem like a setback, it offers a more stable foundation for future research. As Calder and his team make clear, the lack of reliable atmospheric mass data across many exoplanets limits current models. Their work doesn’t close the door on water worlds altogether, it simply urges caution against over-interpretation and reminds the scientific community of the multiple paths planetary evolution can take.