Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

For as long as we’ve been human, we’ve turned our gaze skyward and marveled at all that there is to view beyond planet Earth. Even the recognition that Earth itself is merely one of many planets orbiting the Sun is profound, where the stars glittering up in the canopy of the night sky are just very distant analogues of our own Sun: with many of them likely having their own planets, and where some of those planets might even have life on them. However, arguably the biggest changes that result from viewing the Universe don’t come from merely the scientific knowledge we gain from those astronomical endeavors, but rather how they shift our perception of what reality is, and how we, as humans on Earth, fit into the grand cosmic story.

The images we’ve taken of the Universe — originally merely in the forms of sketches, but later, with the advent of photography, by direct imaging — have quite profoundly shifted how we make sense of ourselves, and our very existence. At every stage, we’ve learned that the Universe is:

grander and vaster than we imagined,

within reach of human understanding,

where our Earth and Sun are both very special (to us) and not very special at all (cosmically),

and, despite all that we may have assumed previously, neither designed for nor centered around us.

These images, carefully selected from both ancient and modern history, serve as examples to show off how just a single image can change humanity’s perspective in a variety of ways: shifting how we view ourselves, as well as the Universe we inhabit.

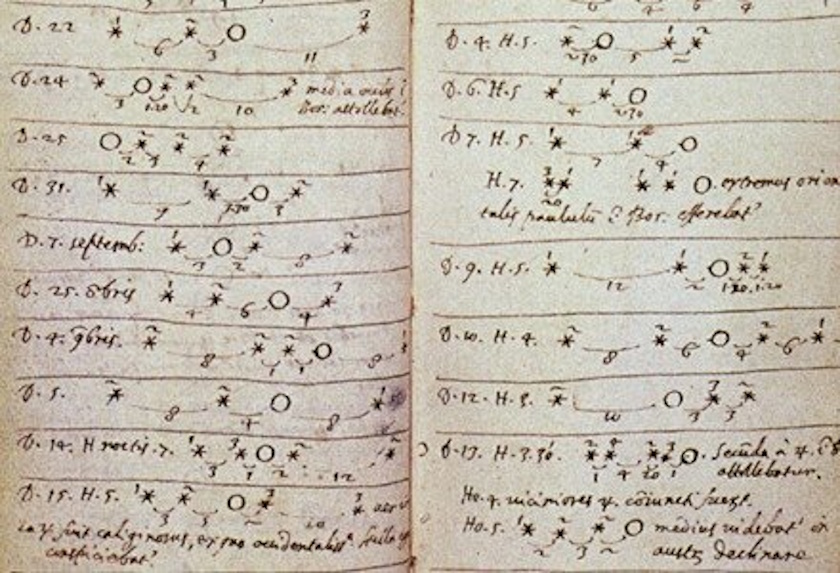

Beginning in 1609, Galileo Galilei modified a spyglass into the first (refracting) telescope, and used it to view several different heavenly bodies. Through it, he saw “ears” on Saturn, phases (including crescent phases) on Venus, and most spectacularly, four large moons orbiting the planet Jupiter. These observations were key in undermining the prevailing geocentric theory of the day, paving the way for Kepler, Newton, and the heliocentric revolution.

Credit: Galileo Galilei, 1610

Galileo’s telescopic glimpse of moons around planet Jupiter.

Back in the early 1600s, our view of the world — and our place in it — was dominated by a narrative that had held sway for thousands of years: the Earth was unchanging and unmoving, and all of the heavenly bodies, including the Sun, revolved around it. Although Copernicus had put forth a heliocentric alternative back in 1543, its matches to the observed orbits for the planets were even worse than Ptolemy’s. (That remained true even when Copernicus attempted to add epicycles to his heliocentric system’s circular orbits.) Meanwhile, in Italy, the Catholic Church flexed its power in executing Giordano Bruno for his cosmological theories: simply for daring to suggest a non-Earth-centric view of reality.

Yet armed with a modified spyglass, serving as the world’s first telescope, Galileo Galilei began observing the heavens in 1609 as no human had done before, and immediately noticed some spectacular features.

Saturn had “ears” to it, now known to be its massive and bright system of rings.

Venus exhibited the full suite of phases, appearing small and “full” when farthest from us, but large and “crescent-like” at closest approach.

And Jupiter, perhaps most spectacularly (as recorded in Galileo’s sketchbook), was found to have four major moons, all of which orbited around Jupiter and definitively not the Earth or Sun.

Contemporaneously, Kepler was working at deriving a heliocentric Solar System with elliptical orbits for the planets, and by century’s end, Newton had concocted the law of universal gravitation. In many ways, the observations of Jupiter were a key turning point in bringing about that tremendous revolution in physics, astronomy, and humanity’s view of our cosmos.

This 1845-era sketch shows the Whirlpool galaxy, Messier 51, and its spiral structure: as first observed by Lord Rosse using his 72-inch telescope, the Leviathan of Parsonstown. At right is a 2005-era image of the same object by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Credit: William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse (Lord Rosse) (L), NASA, ESA, S. Beckwith (STScI), and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) (R)

Lord Rosse’s view of the first spirals ever spotted in the sky.

While today, when we hear of a spiral in the night sky, we immediately default to thinking “galaxy,” the reality is that humanity was very slow to understand the nature of these objects. In fact, it was only in the mid-1800s that our first telescope capable of gathering enough light to reveal the faint, spiral structure of even the closest, brightest galaxies arrived: the 72-inch Leviathan of Parsonstown. Built by William Parsons, also known as Lord Rosse, in Ireland and completed in 1845, it was only with this enormous telescope that spiral structures in these distant nebulae could be revealed.

Rosse recorded these sketches in his sketchbook, and discovered that spirals were actually common. Although there were a few astronomers who asserted that these spirals might be “Island Universes,” or galaxies like the Milky Way, all unto themselves, that was a minority opinion for nearly 80 years. The leading thought of the day was that these were newly-forming protostars: precursors to evolved stellar and planetary systems like our own Solar System. However, even though the question of the nature of these spirals didn’t get resolved until Edwin Hubble’s observations of 1923 settled the issue, the very existence of these spirals represented an enormous leap forward for science, and for humanity.

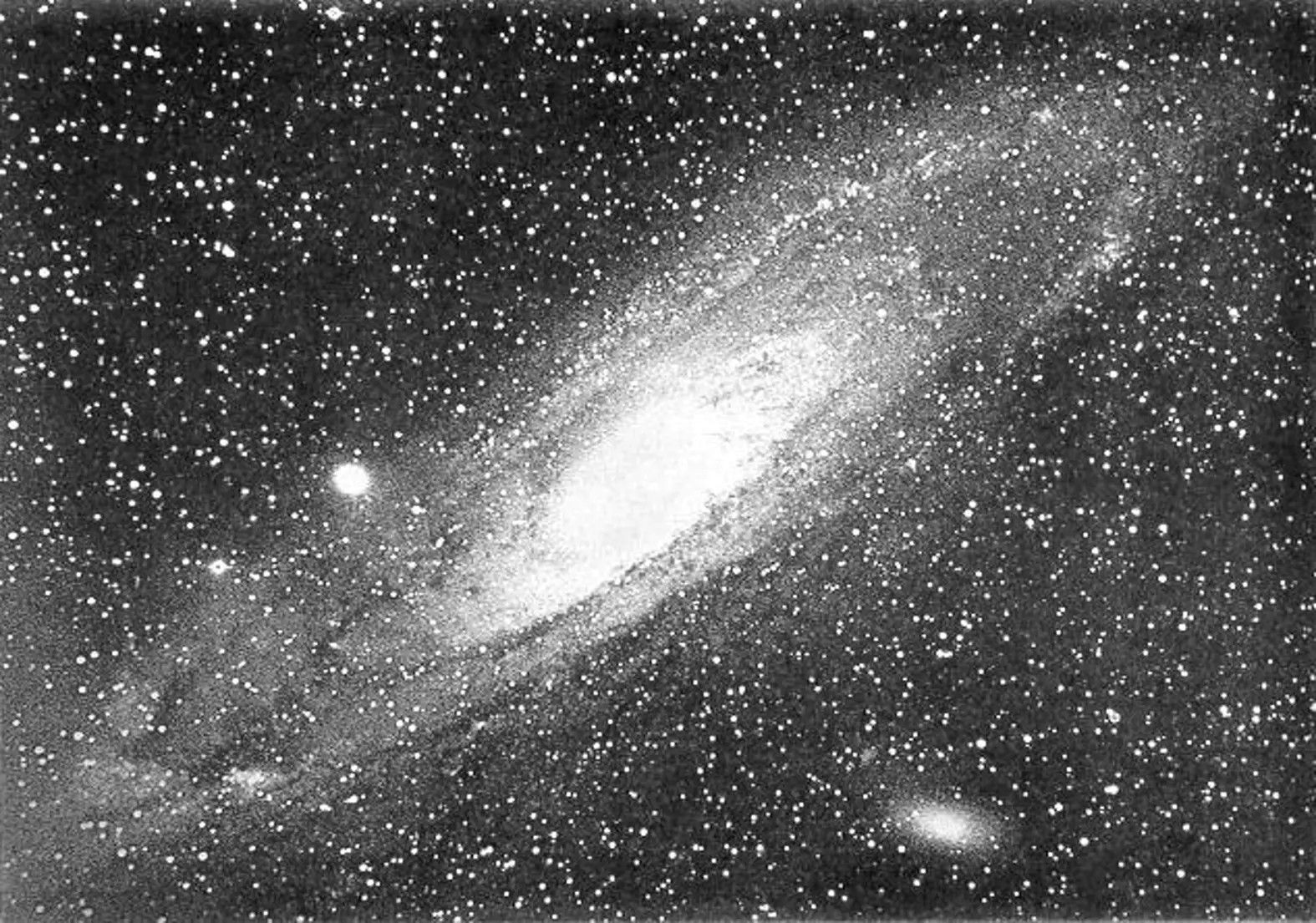

This 1888 image of the Andromeda Galaxy, by Isaac Roberts, is the first astronomical photograph ever taken of another galaxy. It was taken without any photometric filters, and hence all the light of different wavelengths is summed together. Every star that’s part of the Andromeda galaxy has not moved by a perceptible amount since 1888, a remarkable demonstration of how far away other galaxies truly are. Although Andromeda is a naked-eye object under even modestly dark skies, it was not recorded until the year 964, and was not shown to be extragalactic until 1923.

Credit: Isaac Roberts

Isaac Roberts’ photo of Andromeda: the first photo of a galaxy beyond the Milky Way.

Even though Andromeda is the closest, brightest large galaxy outside of the Milky Way, it was only with the advent of astrophotography — or the combination of using telescopes and photography together — that its spiral structure was revealed. Unlike all of the other known spirals at the time, Andromeda isn’t face-on or even nearly face-on to our perspective, but rather is closer to edge-on, being only inclined by about 30 degrees. And yet, because of its proximity to us, it just happened to be the subject of one of the earliest astrophotos ever, as astrophotography only began as an amateur hobby in the 1880s, by Isaac Roberts in 1887/8.

The photo you see, above, actually represented our deepest, most detailed view of any astronomical object at the time, and showed that spirals were very common, and may even be lurking in places where we didn’t expect them. Here in 2026, nearly 140 years later, every star you can see in this image that’s a part of Andromeda (or one of its satellites) is still in the exact same position if you observe it today; Andromeda, at its distance of 2.5 million light-years, hasn’t experienced hardly any perceptual changes in more than a century. This iconic image helped reveal the distant Universe and the Universe beyond our own cosmic backyard, teaching us both that spirals were common, and that they could in fact appear in any orientation relative to us.

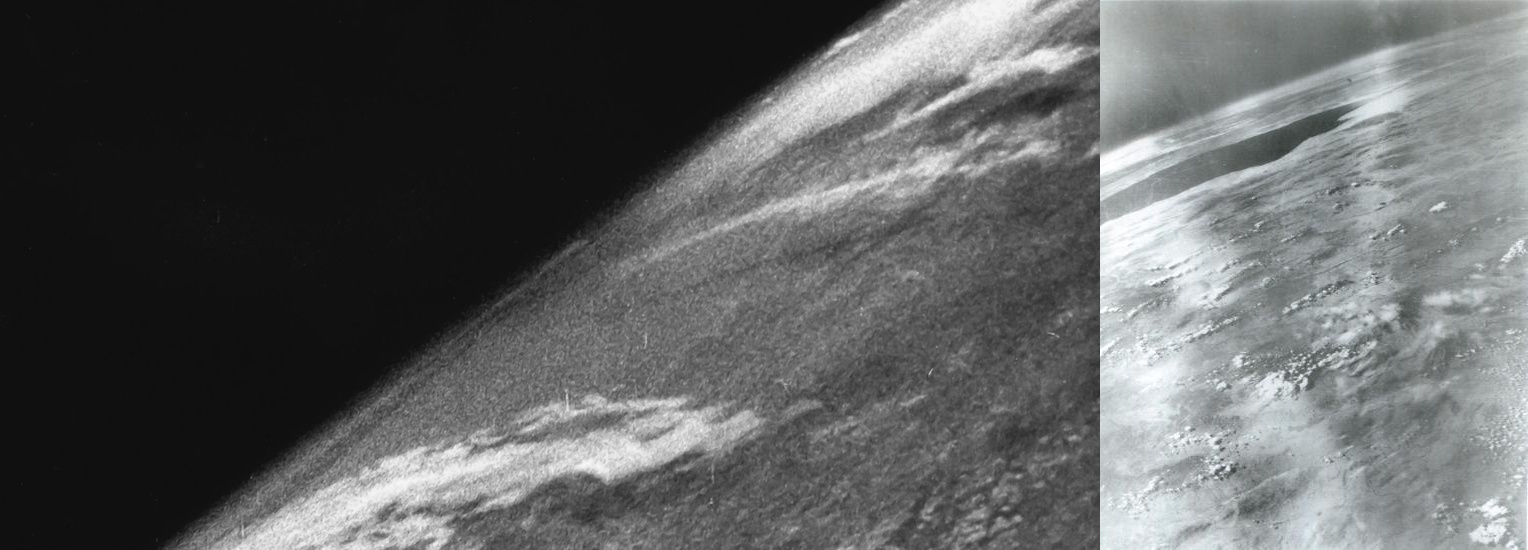

These two photos show the first direct images of the curvature of Earth as taken from high-altitude rockets. At left, an October, 1946 photogram shows the first image of the Earth’s curvature as seen from a human-launched rocket, which reached an altitude of approximately 65 miles. In March of 1947, a similar V-2 rocket saw a view in excess of 100 miles, showcasing Earth’s curvature even more strongly.

Credit: White Sands Missile Range/Naval Research Laboratory, 1946 (L) and 1947 (R)

The first photograph, taken from a rocket, to directly show the curvature of the Earth.

While scientifically, the roundness of the Earth was established more than 2000 years ago, there’s nothing quite like seeing it for yourself: with your own eyes. Conventional airplanes don’t fly high enough for that curvature to be visible, nor even do Earth’s highest mountain peaks. While evidence for the Earth’s curvature had been obtained photographically since the 1930s, those effects were subtle and required special tools (and a lot of math) to detect it.

However, in the post-World War II years, several German V-2 ballistic missiles were captured by various Allied powers, and on October 24, 1946, a 35 mm motion picture camera was attached to one that was launched at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The result can be seen above, at left: where the curvature of the Earth is clearly visible from a single photograph near the rocket’s maximum altitude of 65 miles. Six months later, a second rocket was launched to an altitude of 101 miles, clearly above the Kármán line that delineates the boundary between Earth and space, and saw the curvature even more severely. This was more than a full decade before the launch of Sputnik 1 and the dawn of the space age, but it clearly showed us Earth as it hadn’t been seen before: without national or geographic borders, where only land masses, water features, mountains, cities, farmland, and clouds divided one part of Earth from another.

This photograph shows the first view, with human eyes, of the Earth rising over the limb of the Moon, taken mere minutes after the original Earthrise photo (in black-and-white) was snapped. The discovery of the Earth from space, with human eyes, remains one of the most iconic achievements in our species’ history. Apollo 8, which occurred during December of 1968, was one of the essential precursor missions to a successful Moon landing. This photo is arguably the most environmentally impactful one ever taken.

Credit: NASA/Apollo 8

Earthrise: the first photo of Earth seen rising over the limb of the Moon.

What is it like to see your own planet from so far away? Where you can see the whole sphere of our world, or at least the portion that faces you and is illuminated by the Sun, from a great distance? It’s many things: awe-inspiring, humbling, and makes you feel a sense of care for the fragility of our planet and the life on it. Out of all of the worlds that we’ve ever glimpsed, up close or from afar, Earth is the only known one with life on it, containing more than 8 billion human beings at present.

And yet, from far away, all of the wars we wage, all of the divisions we impose on one another, all of the ways that we contrast ourselves with one another fall by the wayside. All that you feel is a unity, and a need to protect this tiny little blue dot in space: the only hospitable place, and the only home, that we’ve ever known. There’s a name for the feeling that astronauts get when they gaze upon planet Earth from afar: the Overview Effect. In fact, two of the three astronauts aboard that Apollo 8 mission, Frank Borman and Bill Anders (the latter of whom took this now-iconic photo), had extremely memorable quotes about this experience:

“We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.” –Bill Anders

“When you’re finally up at the moon looking back on earth, all those differences and nationalistic traits are pretty well going to blend, and you’re going to get a concept that maybe this really is one world and why the hell can’t we learn to live together like decent people.” –Frank Borman

This image is, even today, arguably the most environmentally and existentially impactful photo ever taken.

On Feb. 12, 1984, astronaut Bruce McCandless ventured farther away from the confines and safety of his ship than any previous astronaut had ever been. This space first was made possible by a nitrogen jet propelled backpack. The contrast between the safety and the life-giving nature of Earth and the lifeless abyss of deep space appears in stark relief in this image. While Earth’s curvature can be seen easily, the fragility of humanity and the hostility of the environment of space are both apparent in this iconic photo, taken during a Space Shuttle Challenger mission.

Credit: NASA/STS-41B

The first photo of an untethered spacewalk: of Bruce McCandless hovering in the distance.

Up until 1984, humans in space had never been free-floating; they had only ever performed tethered spacewalks. That changed with the development and invention of a jetpack, the Manned Maneuvering Unit, suitable for space: a device that would allow astronauts to travel arbitrarily far away from their home station, with the ability to return so long as they didn’t use too much of their nitrogen propellant in the process. The first such untethered spacewalks came during the Space Shuttle mission STS-41B, which used the Challenger shuttle two years before its ill-fated flight. As Bruce McCandless, the astronaut in the photo, later said, “It may have been one small step for Neil, but it’s a heck of a big leap for me.”

Although this image is now more than 40 years old, its impact still resonates today. Up above the Earth, recognizable with its thin atmosphere, wispy clouds, and deep blue oceans, the black abyss of space is joined by a distant human figure: astronaut Bruce McCandless. Floating freely for about an hour and 22 minutes, McCandless’s untethered spacewalk, the very first one, brought him more than 300 feet (91 meters) away from the space shuttle that launched him. Planet Earth, although it looks like it’s just below him, is actually a full 274 kilometers “down” from his perspective. Again, it’s our perspective of humanity, and our place in the Universe, that evolved further with the advent of this photo.

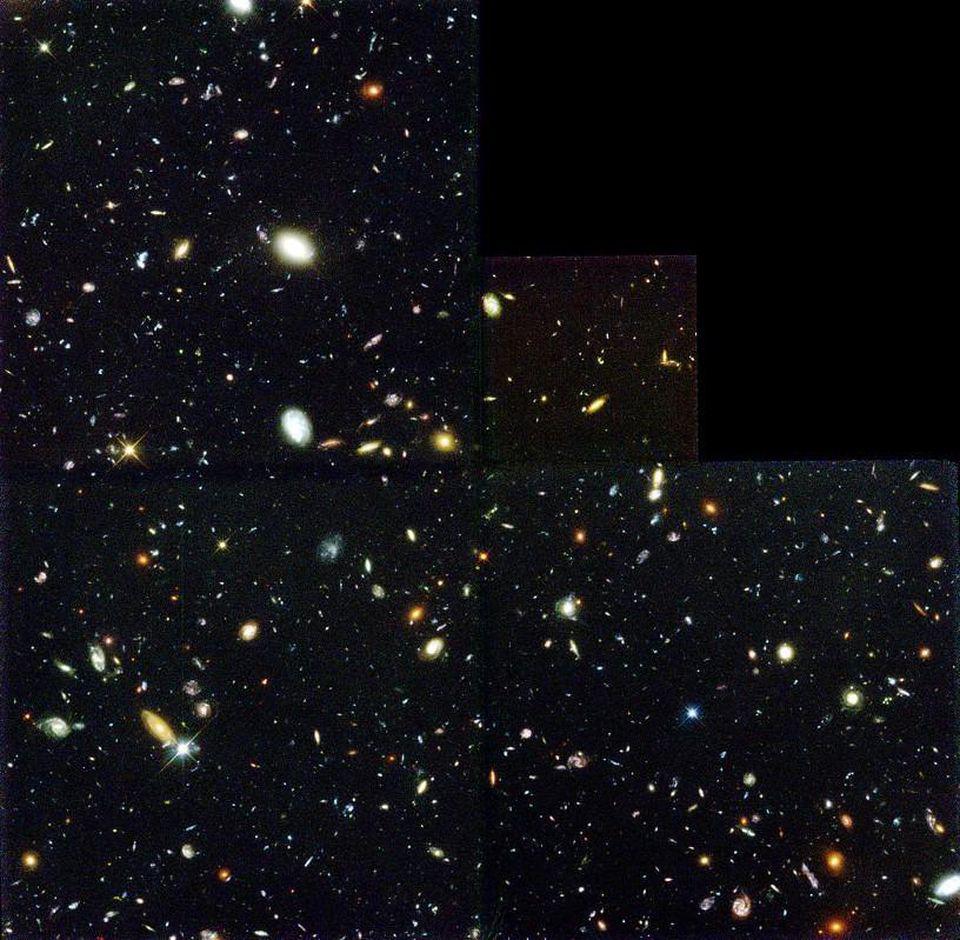

The original Hubble Deep Field image, for the first time, revealed some of the faintest, most distant galaxies ever seen. Only with a multiwavelength, long-exposure view of the ultra-distant Universe could we hope to reveal these never-before-seen objects.

Credit: R. Williams (STScI), Hubble Deep Field Team/NASA

The Hubble Space Telescope’s first-ever deep-field, long-exposure image of… nothing.

Back in the 1990s, after it was serviced and its optics were corrected, the Hubble Space Telescope began taking the deepest, sharpest images of the distant Universe that had ever been obtained. The December 1993 servicing mission saw the corrective optics of COSTAR installed, and also the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2, an upgraded, wide-field camera that enabled superior imaging of the Universe in a variety of ways. But it was the courage of the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, Bob Williams, that would lead to the most iconic space telescope image in history: the original Hubble Deep Field.

Williams put his name, his reputation, and arguably, even his job on the line by devoting his “director’s discretionary time” to a radical idea: that the Hubble Space Telescope would point its eyes at nothing, over and over, across four separate wavelengths, and see what appeared. Many detractors thought it was a waste of the most valuable telescope time ever, but Williams devoted 342 Hubble orbits to the endeavor, all in a patch of sky smaller than a ten-millionth of a square degree.

The result?

Thousands and thousands of galaxies, including many of (at the time) the most distant ones ever detected. It showed us, for the first time, what the faint, ultra-distant universe looked like, leading to our modern picture of the cosmos, where the total number of observable galaxies rises into the trillions.

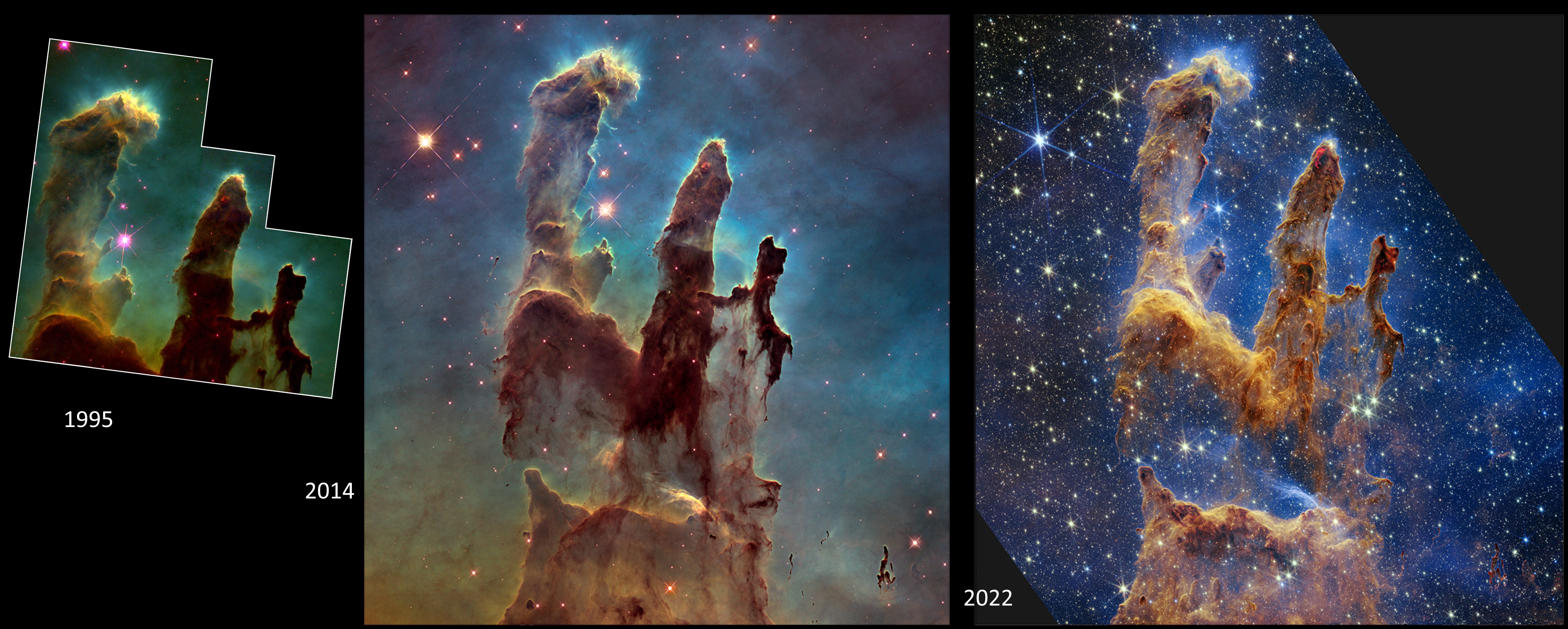

This remarkable three-panel image showcases the same region of space: the Pillars of Creation. On the left, the 1995 Hubble view is shown. At center, the follow-up 2014 Hubble image, with an upgraded instrument suite, is presented. At right, the 2022 view, taken with JWST’s NIRCam imager, is displayed. The variety of features showcases the power of multiwavelength astronomy, but also subtly shows the Pillars shrinking, as external radiation evaporates them away.

Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; the Hubble Heritage Team; J. Hester and P. Scowen; compilation by E. Siegel

Ever-improving views of the Pillars of Creation: a hotbed of star birth right here in the Milky Way.

It may seem hard to believe, but when the original, iconic Pillars of Creation image was snapped by the Hubble Space Telescope back in 1995, it represented a generational leap in showing us the Universe. It showed, for the first time, the precise location, within a star-forming nebula, where new protostars were still assembling and forming, while the outsides of these dust-rich pillars are being slowly photoevaporated by the radiation from the young stars surrounding them.

Then the region was re-observed again: by Hubble with a new camera, by the Chandra X-ray observatory (which found many young stars inside the pillars, as well as more distant background sources), and eventually, by JWST. The pillars aren’t being destroyed by supernova blasts, but rather are only evaporating away extremely slowly: on timescales of 100,000 years or more. The deeper we look:

with higher resolution,

with greater wavelength coverage,

and with the ability to focus on stars, gas, dust, or other unique features,

the better we come to understand where Sun-like stars — and opportunities for living planets — come from. These profound lessons apply not just here in our own backyard, mind you, but all throughout the Universe and all across cosmic history.

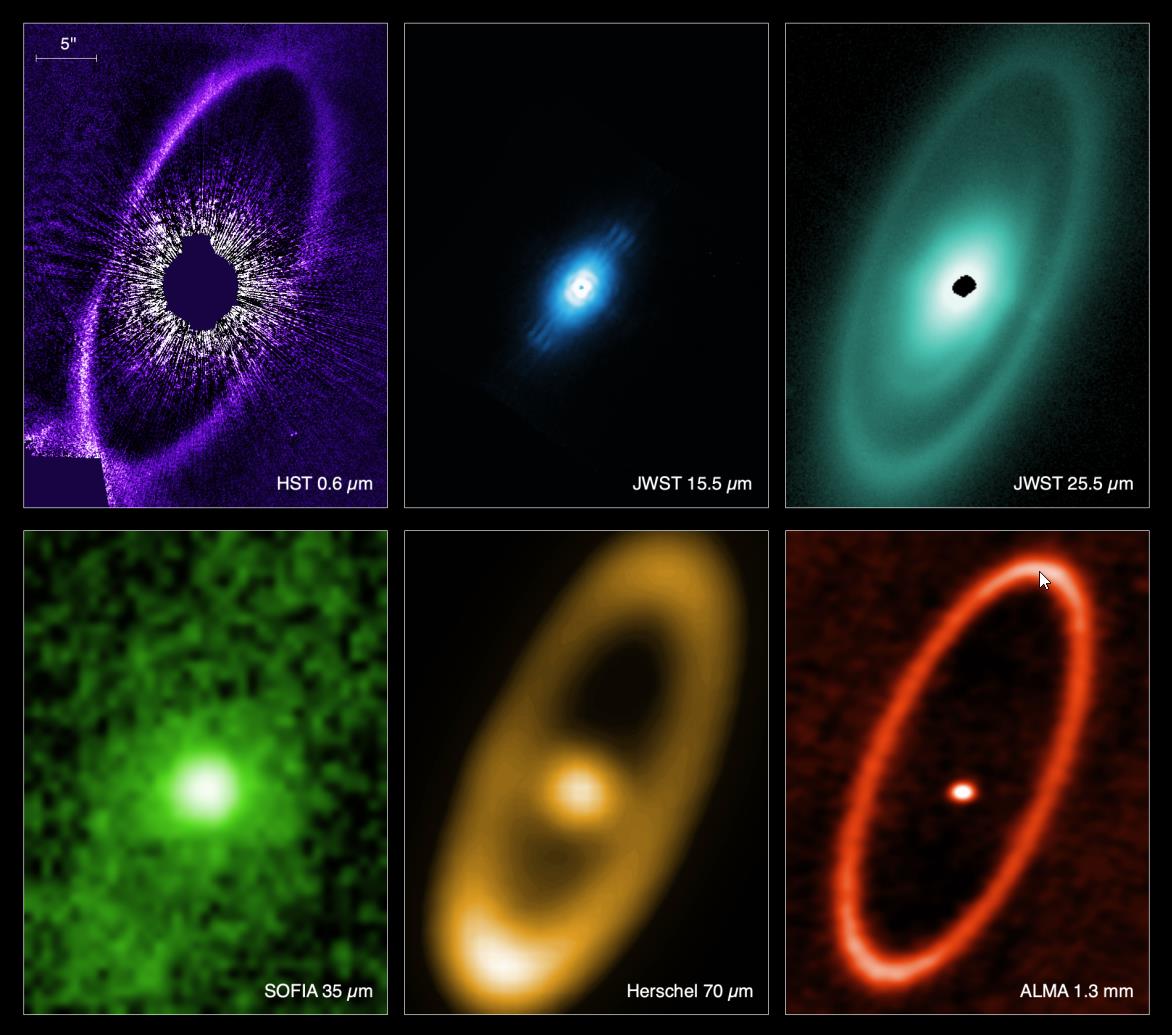

A wide variety of telescopes have looked at the Fomalhaut system in a variety of wavelengths from both the ground and in space. Only JWST, so far, has been able to resolve the inner regions of the dusty debris present in the Fomalhaut system. Whereas Herschel, Hubble, and ALMA data all point to a picture with an inner disk and an outer belt, JWST’s capabilities reveal an “intermediate” belt in between the two. Unlike our Solar System, which has only the asteroid and Kuiper belts, this find was a total surprise.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, A. Gáspár (University of Arizona) et al., Nature Astronomy, 2023

A shocking find from JWST: its view of disks and rings around Fomalhaut, upending our view of our Solar System as typical.

It was only a few years ago, back in 2022, that we had no direct, high-resolution images of debris disks, or asteroid/Kuiper belt analogues, in any stellar system other than our own. We assumed, as would be natural, that the way things unfolded in our Solar System would be the norm. We expected:

inner planets,

an asteroid-like belt, where ices formed/didn’t form early on in the system’s history,

outer planets,

and then a Kuiper-like belt, out beyond the last massive planet.

With the advent of JWST, we finally progressed to the point, technologically, where we could test our expectations directly, by imaging known debris disk systems around nearby stars, like Fomalhaut and Vega.

Fomalhaut went first, and to everyone’s surprise, there weren’t two belts in the system, but three. In addition to an asteroid-like belt and a Kuiper-like belt, there was also an intermediate belt: a property that no one anticipated, and that astronomers are still struggling to explain. But yet, it’s real. Meanwhile, Vega, the second such system to be imaged, shows no evidence for belts of any type, and instead shows a smooth, relatively featureless disk, with no planets as massive as even half of Neptune or Uranus. We used to think that two belts were normal; now we don’t even know if that’s the most common or typical configuration out there.

There’s no doubt that, at some point in the future, there will be another image of space that again upends and enhances our knowledge of the Universe — or our view of our place in it — so profoundly that there will be yet another revolution in how we perceive reality. The key, as always, is to keep looking outward, and based on what we find, to then look inward as well.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.