Researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) are studying neptunium, a rare radioactive element.

It serves as the primary building block for the plutonium-238 used to power long-range spacecraft.

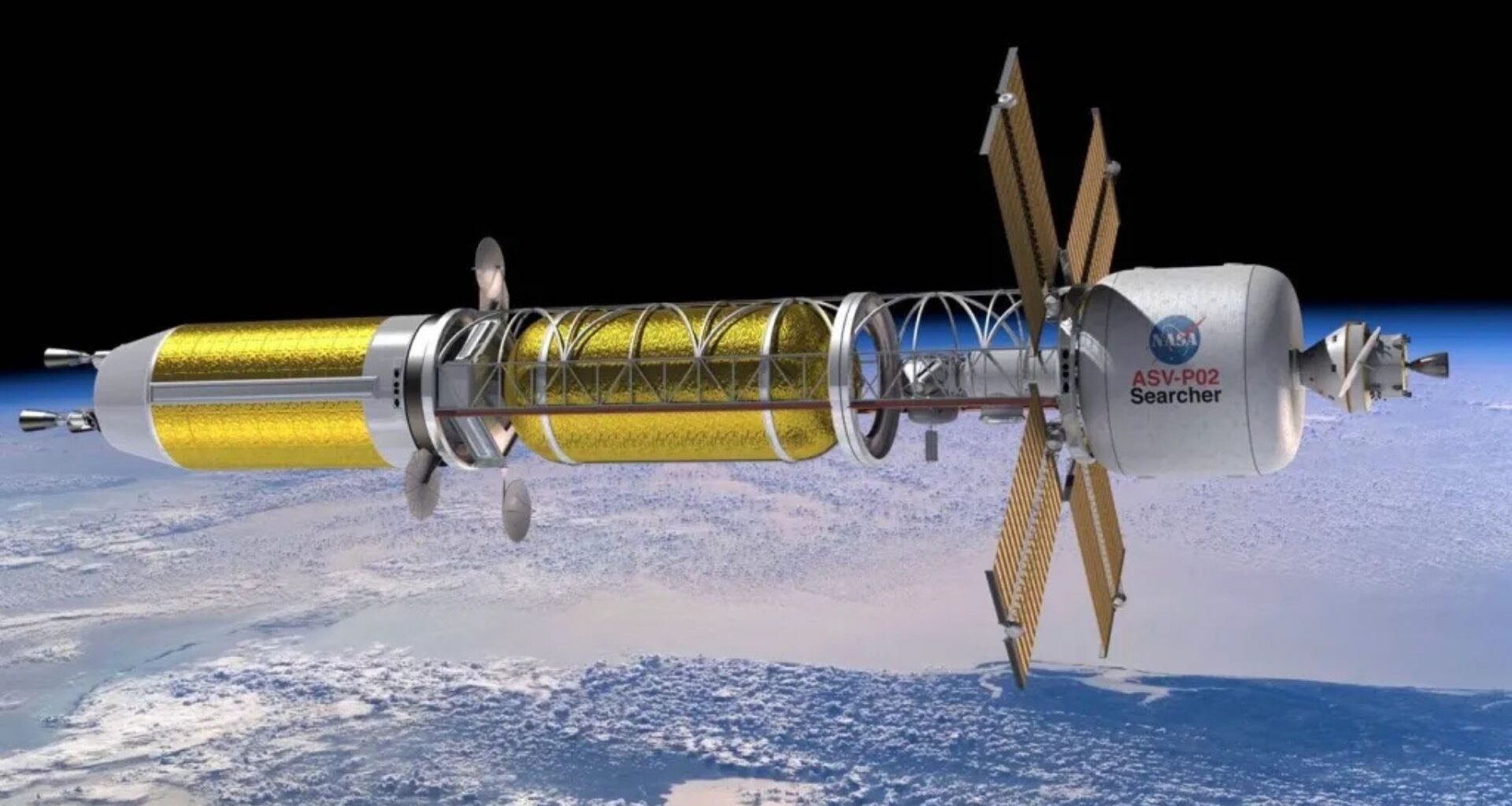

This work is vital for deep-space exploration, as Pu-238 powers the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) used in missions such as NASA’s Perseverance Rover.

RTGs transform the heat from decaying matter into electrical power for spacecraft.

Unlocking neptunium’s secrets

Standard solar panels and lithium-ion batteries are often insufficient for the extreme conditions of deep space.

Hence, plutonium-powered batteries are the only viable solution for sustaining scientific instruments on long-range missions.

As NASA’s ambition for complex space exploration grows, so does the demand for these nuclear power sources, making efficient production a necessity for future discovery.

To maximize the potential, the researchers are working to master the materials science behind RTGs. This involves a rigorous dual focus on both chemical reactions and structural characterization — areas in which ORNL specializes.

“The demand always exceeds our supply. Hence, we need to have a great understanding of neptunium chemistry to support the production of Pu-238,” said Kathryn Lawson, radiochemist in ORNL’s Fuel Cycle Chemical Technology Group.

The team is using a process called thermal decomposition to unlock the chemical secrets of neptunium. The process involves systematically breaking down neptunium using controlled heat between 150°C and 600°C (302 to 1,112°F).

Through this, the ORNL researchers have pinpointed the material’s “intermediate phases,” or the hidden stages it passes through during transformation.

Chemical fingerprint of the element

In this work, the team merged physical data from Raman spectroscopy — which uses lasers to map molecular vibrations — with advanced computational modeling.

It led to an analysis of the internal mechanics of neptunium. This hybrid approach led to the first-ever “structural fingerprint” of a vital neptunium oxide, providing a mathematical and visual roadmap for its behavior.

“Essentially what we do is use Raman spectroscopy to shoot lasers at the sample and excite different vibrations in the structure of the material,” said nuclear security scientist Tyler Spano.

“What comes out is a series of peaks, a spectrum. That tells us something about the current material structure, but what we did was follow the heating pathway that Kathryn [Lawson] uses for the material,” said Spano.

The team performed these measurements under active heating, which provided a step-by-step view of how the material’s bonding environment responded to thermal stress.

Having proven their measurement capabilities, the ORNL team is now moving on to study other poorly understood neptunium compounds.

They aim to uncover new chemical pathways that could further streamline the creation of deep-space fuel.

This research marks a “resurgence” in neptunium study, driven by a tight-knit group of early-career scientists.

Their ultimate goal is to “make the best and the most batteries for space” to ensure that future instruments have the power necessary to explore the furthest reaches of our solar system.