Listen to this article

Estimated 4 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by AI-based technology. Mispronunciations can occur. We are working with our partners to continually review and improve the results.

Some palliative care staff at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver found patient transfers for medical assistance in dying (MAID) to be distressing, a B.C. court heard Thursday.

The procedure is not allowed at the Catholic hospital because it conflicts with church teachings. The legality of transferring patients off-site is being tested in the case, being heard by B.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald Skolrood.

Social worker Chelle Van Dyke was on day three of her job as MAID response lead for Providence Health Care, the Catholic non-profit that runs St. Paul’s, when she heard from another social worker that the transfer of Samantha O’Neill, who had terminal cervical cancer and had requested MAID, was likely to be difficult for both O’Neill and her care team.

Samantha’s mother, Gaye O’Neill, is a plaintiff in the case.

“It was made known to us about the distress of the care team and we reported it,” Van Dyke testified.

Earlier this week, court heard from the person she reported these concerns to: Francis Maza, the vice-president of mission, ethics and spirituality at Providence. In this role, Maza is responsible for ensuring Providence’s operations adhere to Catholic values and ethical directives.

Providence, along with the B.C. Ministry of Health and Vancouver Coastal Health, is a defendant in the case.

WATCH | Why this B.C. case could have national implications:

How a B.C. court case could change medical assistance in dying across Canada

Hundreds of Canadians are transferred between health facilities each year, during their final hours, in order to access medical assistance in dying (MAID). Some health-care facilities don’t allow MAID for religious reasons. CBC’s Tara Carman reports on how that plays out in different provinces.

Maza said he came to the palliative care ward at St. Paul’s just before O’Neill was transferred.

Gaye O’Neill previously testified about the pain and suffering she says her family endured as a result of her daughter’s transfer in her final hours to receive MAID.

Under cross examination by Robin Gage, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, Maza confirmed he was there to support the care team in light of the concerns expressed by some Providence staff.

His recollection of the transfer itself was in marked contrast to that of Gaye O’Neill.

Gaye O’Neill, mother of Samantha O’Neill, is pictured outside of the B.C. Supreme Court, with Sam’s father, Jim, at her side. (Ben Nelms/CBC)

Gaye O’Neill, mother of Samantha O’Neill, is pictured outside of the B.C. Supreme Court, with Sam’s father, Jim, at her side. (Ben Nelms/CBC)

“What I saw was a lot of hugs, a lot of thank yous and appreciation,” he recalled, adding that O’Neill was sedated and calm upon leaving her room on a stretcher.

“I saw a team that was really working together.”

Gage also questioned Maza about a briefing note prepared for Providence leadership in February 2025.

The note discussed the risks and benefits of allowing Providence nurses at St. Paul’s to accompany patients to Shoreline, a dedicated space for MAID provision operated by Vancouver Coastal Health. It is located next to St. Paul’s and opened in January 2025.

Nurses are sometimes needed if there is an intravenous line that needs to be maintained during the transfer.

Banning Providence nurses from accompanying patients was described in the briefing note as having a moral benefit and value as “scandal mitigation,” as it would provide more clarity that MAID is not permitted at St. Paul’s.

“We wouldn’t want anybody to watch this and say, they are doing this for everybody now,” Maza said in court.

Reputational harm to Providence stemming from negative media attention associated with transferring patients off-site for MAID was identified in the briefing note as a risk associated with this approach.

Providence now approves nurses to accompany patients to Shoreline on a case-by-case basis, when the patient needs an IV and Vancouver Coastal Health is not able to provide a nurse. So far, this has only happened twice, Maza testified.

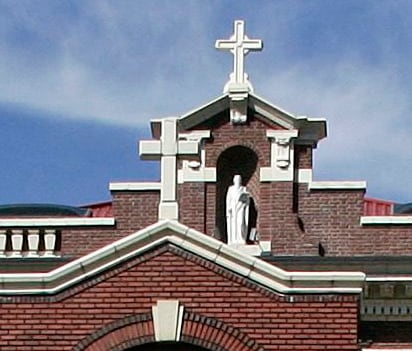

St. Paul’s Hospital in downtown Vancouver is operated by Providence Health Care using public funds. (Richard Lam/The Canadian Press)

St. Paul’s Hospital in downtown Vancouver is operated by Providence Health Care using public funds. (Richard Lam/The Canadian Press)

Scandal associated with the optics of allowing MAID in a Catholic hospital was among the concerns of Vancouver’s former archbishop when he was considering with other bishops how to respond to Canada’s legalization of MAID in 2016.

“We agreed that Third-Party Provision at PHC in any circumstance would violate the Church’s moral teachings on the sanctity of life and the dignity of the human person,” retired Archbishop J. Michael Miller wrote in an affidavit.

“Furthermore, I was concerned that public scandal would result from Third-Party Provision at PHC: that it could confuse some Catholics and lead them to believe that the Church viewed euthanasia as morally acceptable.

“Catholic doctrine is unambiguous that euthanasia and MAID are not permissible. As such, the decision on Third-Party Provision at PHC was ultimately a clear no.”

The trial continues.