US physicists have shed light on a long-standing mystery after they captured rare experimental evidence that links the fleeting virtual “nothingness” of the quantum world to the formation of real, detectable matter.

The discovery was made by the STAR Collaboration at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory’s (BNL) Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC). RHIC is the world’s first heavy-ion collider.

For the study, the BNL researchers analyzed millions of proton-proton collisions. They specifically focused on pairs of particles known as lambda hyperons and their antimatter counterparts.

These short-lived particles are particularly useful to scientists, as the orientation of their quantum spin, a crucial property related to magnetism, can be reconstructed from how they decay. The team now realized that when lambdas and antilambdas are produced close together in a collision, their spins are perfectly aligned.

“This work gives us a unique window into the quantum vacuum that may open a new era in our understanding of how visible matter forms and how its fundamental properties emerge,” Zhoudunming (Kong) Tu, PhD, a STAR physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory and co-leader of the study, stated.

From vacuum to reality

The vacuum is not empty. It is in rather, filled with fluctuating energy fields that can create entangled particle–antiparticle pairs. These “virtual” and inherently linked particles, disappear before they can be observed and counter as real.

Yet when protons slam together at near-light speeds inside the RHIC they provide enough energy to promote some of these virtual quark-antiquark pairs into real particles. They can be tracked down by the STAR Collaboration detector.

For the research, the scientists searched for lambda hyperons and their antimatter counterparts, antilambdas. They sought to determine whether and to what extent, the particles’ spins aligned as they emerged from RHIC collisions.

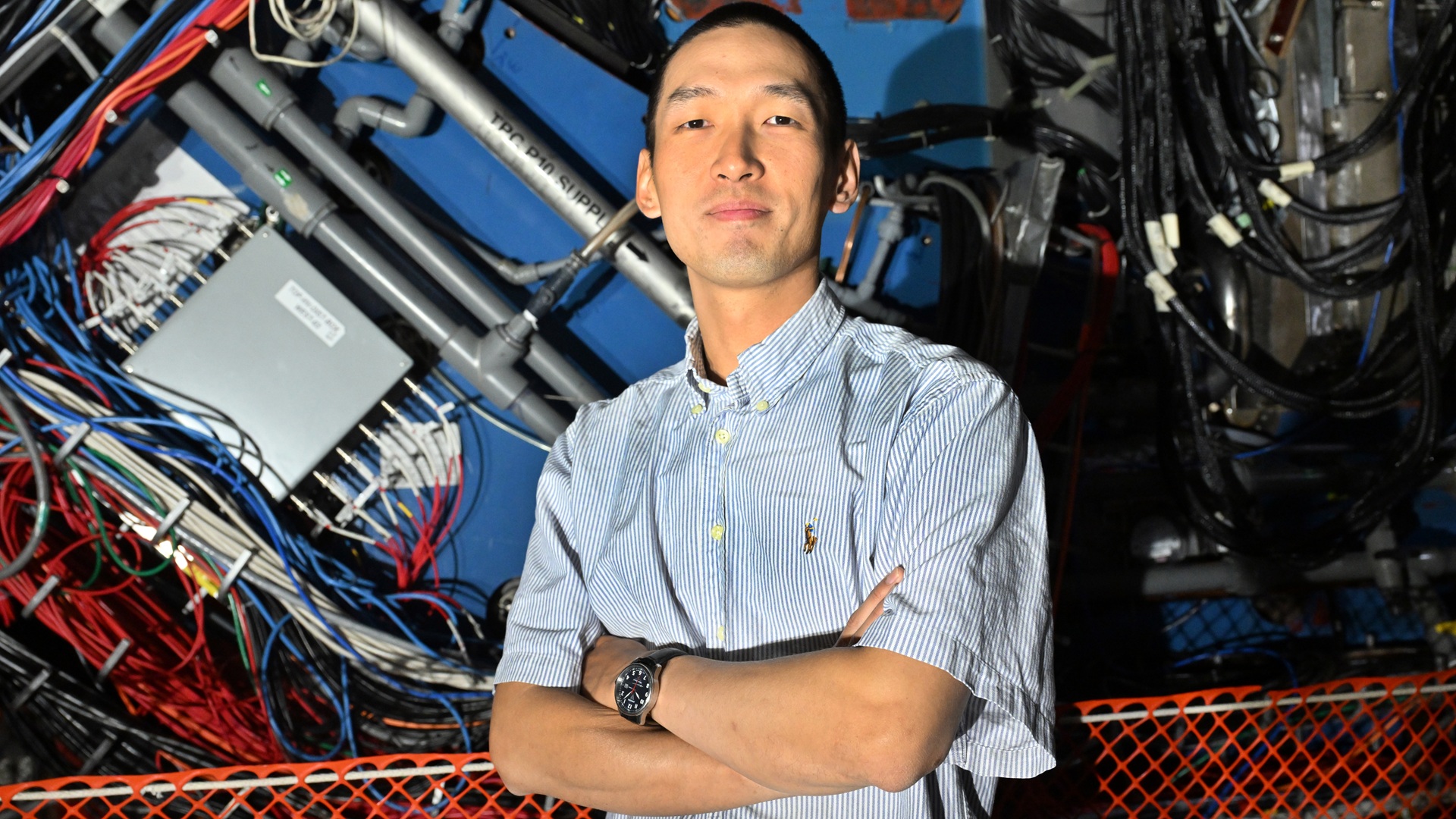

Zhoudunming Tu, PhD, a physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory, in front of the STAR experiment/detector.

Zhoudunming Tu, PhD, a physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory, in front of the STAR experiment/detector.

Credit: Kevin Coughlin/Brookhaven National Laboratory

Lambdas are ideal for spin research because the direction of a lambda’s spin can be inferred from the direction in which a proton or antiproton is emitted during its decay. Each lambda also contains a strange quark, or a strange antiquark in the case of an antilambda, which allows physicists to trace its origins.

Virtual strange quark–antiquark pairs are always spin aligned. Detecting the same alignment in the spins of lambda–antilambda pairs strongly suggests that the strange quarks inside them originated as a single entangled pair in the vacuum.

“Normally, in a RHIC collision, the spins of the vast majority of particles that come out are randomly oriented,” Jan Vanek, PhD, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire, said. “We are looking for a very tiny difference from all those other particles to find lambda/antilambdas where their spins are correlated.”

A quantum connection

The team analyzed millions of proton–proton collisions. They found that lambdas and antilambdas emerging close together are perfectly spin-aligned, similarly to the virtual quark/antiquark pairs in the vacuum.

“It’s as if these particle pairs start out as quantum twins,” Vanek explained. “When they’re generated close together, the lambdas retain the spin alignment of the virtual strange quarks from which they were born.”

Tu noted that this is the first direct evidence that these quarks originate from the quantum vacuum. “It’s amazing to see that the spin alignment of the entangled virtual quarks survives the process of transformation into real matter.”

The team believes that the effect could point to deeper quantum entanglement between lambda–antilambda pairs. Interestingly though, it disappears when the particles are produced farther apart in RHIC collisions.

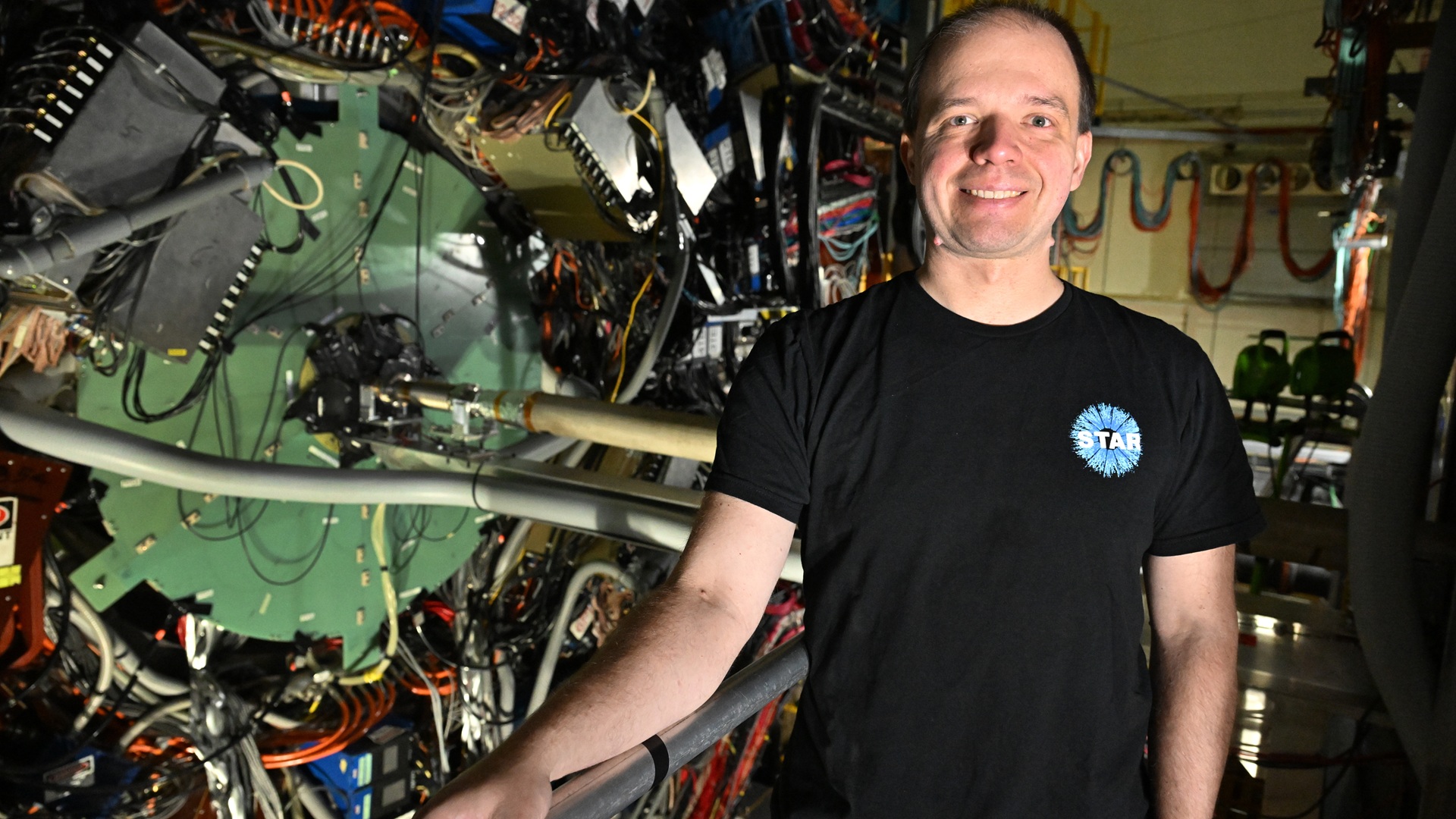

Jan Vanek, PhD, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire, in front of the STAR experiment/detector.

Jan Vanek, PhD, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire, in front of the STAR experiment/detector.

Credit: Kevin Coughlin/Brookhaven National Laboratory

“It could be that these twins sent farther away from each other are more affected by other things in their environment, interactions with other quarks, for example, that cause them to behave differently and lose their connection,” Vanek said.

According to the researchers, the transition from quantum-connected behavior to ordinary classical physics, is one of the most important open questions in science, with implications for quantum computing and information technologies.

The findings open a novel way to probe how quarks become bound into protons, neutrons, and other particles. “How something – the visible matter of the universe – connects to the ‘nothingness’ of the vacuum,” Tu concluded in a press release.

The technique could also be extended to collisions involving atomic nuclei and to experiments at the future Electron-Ion Collider. The study has been published in the journal Nature.

Based in Skopje, North Macedonia. Her work has appeared in Daily Mail, Mirror, Daily Star, Yahoo, NationalWorld, Newsweek, Press Gazette and others. She covers stories on batteries, wind energy, sustainable shipping and new discoveries. When she’s not chasing the next big science story, she’s traveling, exploring new cultures, or enjoying good food with even better wine.