Early 2026 has brought renewed scrutiny to how Earth-observing satellites register extreme ocean events. Widely circulated reports have pointed to satellite detections of unusually large Pacific Ocean waves, creating uncertainty about whether the observations reflect new hazards or improved measurement capability.

At the center of the attention is a single satellite mission whose measurements intersected with separate phenomena within a short timeframe. In one instance, the data recorded the faint signature of a major tsunami traveling across the open ocean. In another, similar instruments captured severe storm waves generated by powerful weather systems. The shared technology, rather than shared physics, has blurred the public narrative.

What the verified evidence shows is not an escalation of ocean risk, but a clearer window into processes that scientists have studied for decades. Advances in satellite altimetry have reached a level of resolution that reveals details once accessible only through sparse in-situ measurements, amplifying both understanding and misinterpretation.

A Rare Satellite View of a Major Pacific Tsunami

The most rigorously documented development comes from peer-reviewed research published in The Seismic Record, which analyzed the tsunami produced by the magnitude 8.8 earthquake off the Kamchatka Peninsula in 2025.

During the event, the Surface Water and Ocean Topography satellite crossed the North Pacific, capturing the tsunami wavefield in deep water. The full scientific analysis is detailed in the journal article examining SWOT satellite altimetry observations and tsunami source modeling published by the Seismological Society of America.

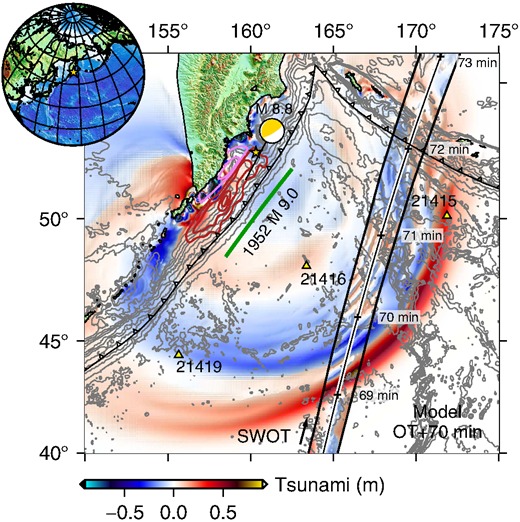

Propagation of the 2025 tsunami across the Pacific Basin with arrival times (in minutes) at DART buoys and the SWOT satellite’s overpass path. Credit: The Seismic Record

Propagation of the 2025 tsunami across the Pacific Basin with arrival times (in minutes) at DART buoys and the SWOT satellite’s overpass path. Credit: The Seismic Record

Researchers reported that SWOT detected coherent changes in sea surface height across a wide swath, with amplitudes ranging from centimeters to several tens of centimeters. These values align with established tsunami theory, which predicts low-amplitude, long-wavelength waves in deep ocean basins. Unlike conventional altimeters that observe only a narrow ground track, SWOT provided a two-dimensional snapshot of the propagating wavefield.

The satellite measurements matched independent observations from the DART, the deep-ocean network operated by NOAA to support tsunami detection and warning. DART buoys rely on seafloor pressure sensors to identify passing tsunamis in near real time, a system NOAA describes in detail through its Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis program. SWOT data were analyzed after the event and were not used operationally.

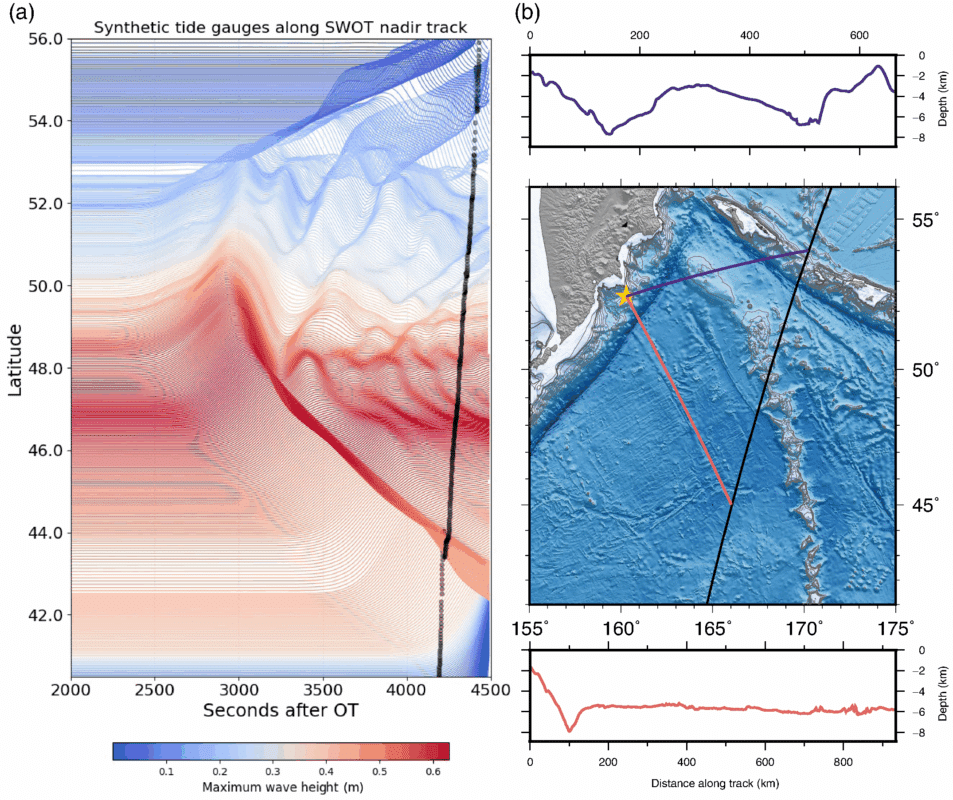

Synthetic tide gauge data simulated along the SWOT nadir track, showing the complexity and modulation of wave heights over time and space. Credit: The Seismic Record

Synthetic tide gauge data simulated along the SWOT nadir track, showing the complexity and modulation of wave heights over time and space. Credit: The Seismic Record

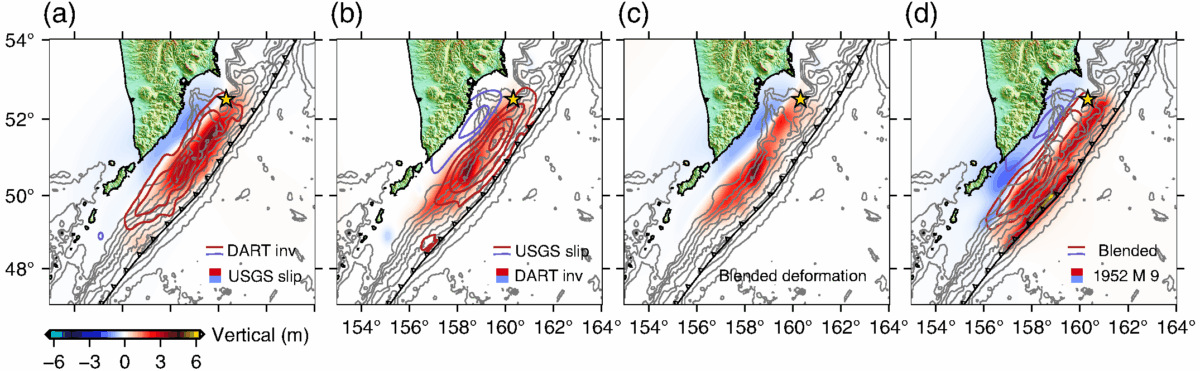

By integrating satellite altimetry with seismic and geodetic datasets, the researchers refined estimates of the earthquake’s rupture characteristics, including fault slip distribution. The study characterized this as an advance in post-event scientific reconstruction. Mission documentation from NASA underscores that SWOT was designed as a research platform to map ocean topography and surface water rather than as a real-time hazard warning system.

How Storm Waves Entered the Discussion

Parallel reporting focused on claims that satellites had identified waves approaching 35 meters in height in the Pacific Ocean. These claims trace back to altimetry measurements collected during an intense North Pacific storm in late 2025. The relevant parameter was significant wave height, a standard oceanographic metric describing the average height of the highest third of waves within a sea state.

During the storm, satellite instruments recorded significant wave heights near 20 meters. Established wave statistics show that individual waves can occasionally exceed the significant wave height by a substantial margin under such conditions. Some coverage extrapolated this relationship to estimate the possible presence of waves exceeding 30 meters.

Comparison of vertical deformation and slip models derived from USGS, DART inversion, and blended datasets. The final blended model extends farther south than initial estimates. Credit: The Seismic Record

Comparison of vertical deformation and slip models derived from USGS, DART inversion, and blended datasets. The final blended model extends farther south than initial estimates. Credit: The Seismic Record

Ocean scientists emphasize that these figures do not describe tsunami behavior and do not represent a direct observation of a single extreme crest by satellite. Storm-generated waves are driven by wind energy, have short periods, and decay as atmospheric conditions change. Tsunamis arise from sudden seafloor displacement, travel across ocean basins as long-period waves, and exhibit fundamentally different dynamics.

The storm-wave values fall within ranges documented by earlier satellite missions and shipborne measurements. What has changed is the spatial detail available from modern altimetry, which now allows researchers to resolve wave fields with greater precision across wide ocean areas.

What Satellite Altimetry Adds to Ocean Monitoring

Satellite radar altimetry has supported global ocean observation since the early 1990s, contributing to weather prediction, climate analysis, and marine operations. Earlier missions sampled sea surface height along narrow tracks, leaving gaps between passes. SWOT’s interferometric design allows it to map a broad corridor, revealing spatial patterns that were previously inferred indirectly. NASA and its partners describe this capability as central to the mission’s scientific objectives.

That capability comes with constraints. SWOT revisits the same locations on multi-day cycles, and its data require careful calibration and processing. These factors limit its role to research and post-event analysis rather than immediate hazard response. Operational tsunami alerts continue to rely on in-situ sensor networks such as the DART buoy system, and storm wave warnings depend on meteorological observations and numerical models.

The tsunami study explicitly documented sources of uncertainty, including background ocean variability that can mask small signals and the rarity of favorable satellite geometry. These limitations were presented as inherent characteristics of the measurement approach rather than deficiencies of the mission.