A UBC-led team of researchers has discovered two chemical compounds with potent and wide-ranging antiviral activity that protect mice from influenza A infection.

Their study, published in Emerging Microbes & Infections, provides a valuable starting point for developing new drugs to treat not only influenza but a larger family of viruses that work via the same mechanism.

“The discovery of novel, broad-spectrum antivirals that target existing and newly emerging human viruses is essential for pandemic preparedness,” said co-first author Lianne Presley, who conducted the research in the lab of Professor François Jean in UBC’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology. “Although the SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A viruses have caused global pandemics, there is no clinically approved broad-spectrum antiviral that is effective against both of these human pathogenic viruses.”

The Jean lab is a global leader in the development of host-directed antivirals, which target the factors in the host cell that the virus exploits to infect the cell rather than the virus itself. By shuttering a home’s entry points instead of disarming the invader, host-directed antivirals are effective against many different invaders, regardless of the specific tools they’re wielding.

In previous studies, Jean’s team identified compounds that inhibit human TMPRSS2, an enzyme in the host cell that viruses including SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A use to access the cell. One inhibitor called N-0385 prevented infection from Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta SARS-CoV-2 variants, while an optimized molecule called N-0920 blocked out Omicron variants when the drug was present at just picomolar concentrations.

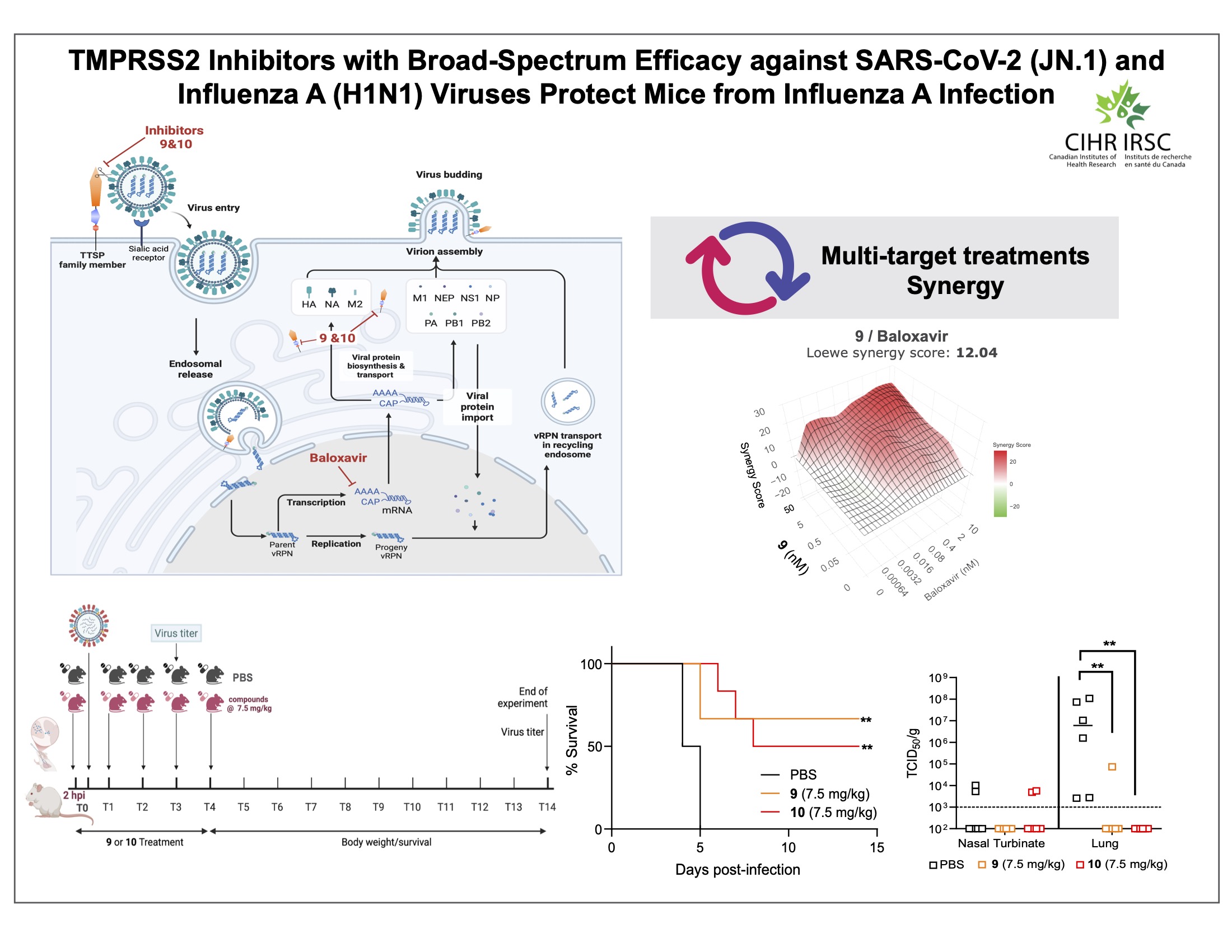

In the new study, the researchers further tweaked the compound’s structure to enhance its stability and ability to penetrate the cell membrane, creating 12 analogs. They tested this library in human lung cells and identified two molecules that effectively inhibited TMPRSS2 and stopped both a SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant and the H1N1 influenza A virus from infecting the cells. “These findings demonstrate that our TMPRSS2 inhibitors are strong candidates for preventative and therapeutic use against both of these viruses and reveal that TMPRSS2 is an attractive target for broad-spectrum antiviral therapies,” said Professor Jean.

The team then treated the cells with one of these TMPRSS2 inhibitors along with an existing antiviral for influenza A and observed that the combination produced an effect greater than the sum of each part. This synergism enables a lower dose of each drug to be used, minimizing side effects, and helps to combat resistance to antivirals, which is more likely to emerge when one therapeutic is administered on its own.

The team then tested the TMPRSS2 inhibitors in mice infected with a lethal dose of the H1N1 virus. They found that treatment with either compound significantly reduced viral levels in the lungs, prevented signs of clinical disease including weight loss, and greatly improved survival outcomes. “With the first demonstration in mouse models, this work provides crucial preclinical validation for TMPRSS2 inhibitors as potential influenza therapeutics,” said Professor Jean.

TMPRSS2 inhibitors display broad-spectrum activity against SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A viruses and protect mice from influenza A infection. (Image courtesy of Jimena Pérez-Vargas, co-first author of the study)

The current flu season, touted as the worst in 25 years, is driven by subclade K, a variant of the H3N2 influenza A virus. Other researchers have shown that using gene editing tools to eliminate the TMPRSS2 enzyme in mice protects them against disease and death from H3N2, indicating that this virus also uses TMPRSS2 to enter the cell. “We therefore hypothesize that our TMPRSS2-directed inhibitors are effective against newly circulating H3N2 influenza A strains and are preparing to test this working hypothesis using infected patients’ respiratory samples,” said Professor Jean. The gene editing studies in mice have also shown that TMPRSS2 is non-essential for normal physiological function, suggesting that drugs inhibiting this enzyme will not yield adverse effects.

While their inhibitors have so far been formulated as an intranasal solution, the researchers are also working to adjust the compounds’ chemical structure to make them compatible with oral delivery. They hope that their efforts will expand access to antivirals, which have been underutilized in the fight against influenza, in order to reduce the burden of viral pathogens and bolster public health.

The development and testing of TMPRSS2-directed inhibitors is funded via a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant lead by Professor Jean at UBC. Lianne Presley was a recipient of a Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) Canada Graduate Scholarship – Master’s Award. The mouse studies were performed by Dr. Bryce Warner, Early-Career Investigator at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO), University of Saskatchewan. The TMPRSS2 inhibitors were developed by Drs. Pierre-Luc Boudreault and Richard Leduc and their team at Université de Sherbrooke.