Multilateral global trading system on the altar of Davos 2026

Maaal, Saudi Arabia, January 26

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

What is my impression of the Davos 2026 Forum? It depends on where you look. The Saudi delegation, for example, was a beehive of activity, with an intensive agenda packed with bilateral meetings, dialogues, interviews, and engagements, all underpinned by an economy that continues to diversify and grow year after year, and by a vision that is being realized despite mounting challenges – and indeed, despite the expectation of even more challenges ahead.

If you look from another angle, however, you encounter what might be called “conditional cooperation,” as the Davos Forum revealed a noticeable shift toward the trend of cooperating only with friendly countries, and not with the rest of the world. In practice, this signals a sidelining of the rules-based system and the World Trade Organization, replaced by a fragmented global order in which flexibility takes precedence over efficiency.

From yet another perspective, the risk of geopolitical fragmentation loomed large: Davos 2026 confirmed in one of its own reports that geo-economic fragmentation is no longer merely a potential threat, but has become a framework enveloping global trade, finance, and security.

When listening to the speeches of Western leaders, one senses that the West has turned inward; tense exchanges over trade confrontations between the US, EU, and Canada dominated the atmosphere to the point that regional segmentation eclipsed – and effectively displaced – the official slogan of Davos 2026, the so-called “spirit of dialogue.”

The one relatively bright corner was artificial intelligence, which, despite the class divide it deepens between those who possess it and those who do not, still promises investment-driven prosperity and offers a glimmer of hope that there remains at least one axis capable of bringing countries together.

The overall conclusion, then, is that deep geopolitical and commercial fragmentation dominated the discussions at Davos.

In Davos 2026, the world also witnessed a new kind of friction among allies, particularly between the US and Europe, culminating in the cancellation of President Emmanuel Macron’s Group of Seven summit and President Donald Trump’s blunt declaration that Macron’s days were numbered. All of this unfolded while the Chinese dragon lay quietly in a nearby corner, observing calmly and waiting to reap gains, even before the dust settled.

There is a strong case to be made that China emerged as the biggest beneficiary. At Davos 2026, China presented itself as a calm and reliable leader amid President Trump’s controversial foreign policy. In contrast to the unilateralism and protectionism openly championed by the Trump administration, China emphasized multilateralism and free trade as core principles, insisted on adherence to rules, and emphasized the importance of globalization. From my perspective in the Gulf Cooperation Council region, I am not overly preoccupied with what Trump will ultimately do with Europe, because the US and the EU are not fundamentally different in how they view the rest of the world: as markets for exporting equipment, weapons, technologies, and services, and as destinations for tourism revenues.

Most likely, their current confrontation will end in a different kind of understanding because Trump, regardless of his rhetoric, cannot afford to abandon Europe and allow it to drift fully into China’s orbit. From the same perspective, the real concern lies in the geopolitical repercussions of President Trump’s policies and their potential to profoundly restructure the global economy, beginning with the redistribution of international trade and the rewriting of the rules governing its facilitation and operation, potentially declaring the death of the World Trade Organization or rendering it irrelevant.

Under such a framework, a country’s trade deficit or surplus with the US would become the measure of its proximity to peace and harmony, while the “stick” of tariffs would be ready for those who challenge Washington as we have seen throughout the first year of Trump’s second term with Canada and Mexico despite an existing free trade agreement he himself signed during his first term, with the EU, China, and most recently with France for French wines.

It is no secret that reshaping the rules of international trade will inevitably affect global stability, because restructuring entails the repositioning of global supply chains, the reprioritization of foreign direct investment flows, and ultimately a geo-economic redistribution of growth, prosperity, stagnation, and poverty across the world, leading to profound socioeconomic shocks. What makes this danger particularly ominous is the reality that the global economy is a single interconnected fabric, binding countries together and transmitting both negative and positive shocks alike, as evidenced by phenomena such as inflation driven by imports and the economic tremors caused by sudden price changes or supply disruptions – vividly experienced worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic.

So what is the solution? Despite the White House’s clear inclination to marginalize the existing world order, multilateral institutions – particularly those under the UN umbrella, including the World Trade Organization (WTO) – must be protected and reinforced to preserve global stability in general and the global economy in particular. Abandoning a rules-based multilateral trading system would mean sliding into a chaotic world marked by escalating trade disputes, heightened risks of conflict, and the squandering of nearly half a century of collective effort to regulate global trade. – Ihsan Buhulaiga

No better alternative to Trump’s Board of Peace

Al-Ittihad, UAE, January 27

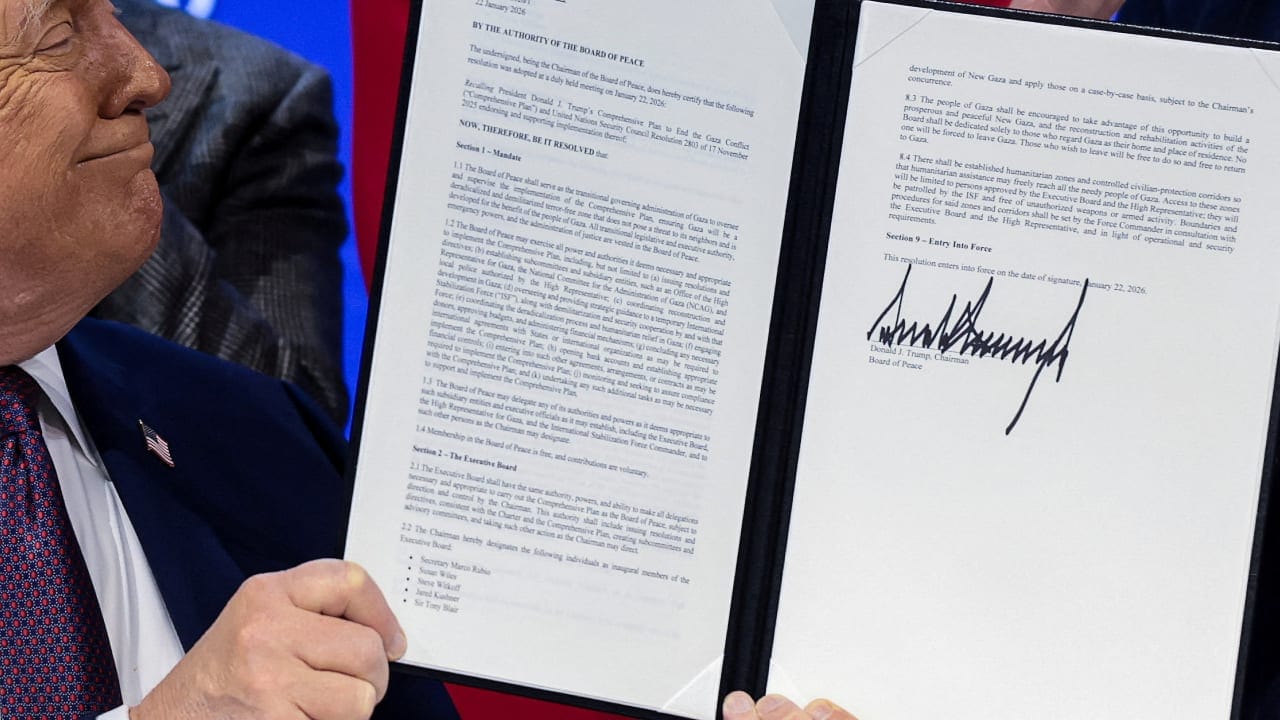

US President Donald Trump announced the formation of a Board of Peace and succeeded in attracting more than 30 countries to the idea before complaints and reservations began to escalate. He pointed out that a number of major European countries had not yet joined, as some viewed the initiative as vague and ill-defined.

Among the most prominent skeptics was the well-known American journalist Thomas Friedman, who wrote in The New York Times that under Trump, the US no longer takes into account the interests of its allies nor engages seriously in negotiating with its opponents.

Yet the central question remains: What possibilities and alternatives exist in light of the tragedy that has been unfolding for over two years in Gaza and the West Bank? It is evident that the UN and its various commissions have been unable to deliver results, just as the traditional mediating countries have failed, leaving little on the table other than Trump’s initiative.

Trump was able to impose a ceasefire through the Sharm El-Sheikh Peace Summit and secure the withdrawal of the IDF from half of the Gaza Strip, even if Israeli killing did not cease entirely. With the start of the second phase, two developments followed: First, the formation of a committee to manage civilian sectors in the Strip, the opening of land crossings, and the clearing of a path for the entry of international forces tasked with disarming Hamas and establishing security, allowing the Israeli army to gradually withdraw from the entire Strip, amid Israeli and American threats over what will happen if Hamas refuses to disarm.

The second development was Trump’s announcement of the Board of Peace, to be chaired by him, with the aim of rebuilding Gaza, thinking about its future, and reviving the two-state solution. Once again, Israel agreed to participate only reluctantly and is expected to hesitate and object at every step, however small; Netanyahu rejects the deployment of Turkish troops in Gaza and refuses any reference to a two-state solution within the project.

In light of all this, the obstacles are significant, yet no one has put forward a viable alternative that Palestinians and Arabs could reasonably reject, since the core elements of the proposal align with the vision they have presented to the Trump is a leader with a distinctive personality, and what he has done with Venezuela and is doing with Greenland raises serious objections in terms of international law, state sovereignty, and the norms governing international relations since the end of World War II. Still, his proposal for Gaza, despite its many gaps and unanswered questions, remains the only concrete plan on the ground, offering a measure of stability and the possibility of progress toward certain human and political rights for the Palestinian people.

In wars of domination, it is an illusion to demand peace and justice simultaneously from the strong. The ceasefire is on the verge of being consolidated, the management committee is stepping in to stabilize it, and the Board of Peace promises a different future for Gaza. This is the opportunity that Arab and international participants in both the steering committee and the Board of Peace must seize. Let us begin speaking about justice under American guarantees, for there are no others available. – Radwan al-Sayed

Feminism: Addressing root causes, not just visible outcomes

Al Rai, Kuwait, January 27

The question of prioritizing feminism over human rights is often a nuanced and multifaceted issue, shaped by multiple perspectives. At first glance, it may appear that human rights should take precedence, since they encompass the rights and dignity of all human beings regardless of gender, race, class, or any other characteristic. However, feminism is a movement specifically concerned with women’s rights and empowerment, addressing a group that has historically faced marginalization, discrimination, and persecution.

To understand why feminism is sometimes treated as a distinct priority within the broader human rights framework, it is necessary to examine the history of the women’s rights movement and the ways in which women were frequently excluded from mainstream human rights discourse. Although human rights are intended to be universal and inclusive, women’s lived experiences and perspectives have often been ignored, minimized, or sidelined.

Feminism emerged, in part, as a response to that exclusion, seeking to highlight and confront the particular struggles and challenges women face. One of the primary reasons feminism is emphasized within human rights is that women’s experiences and perspectives are both unique and indispensable.

Under patriarchal systems, women have long been subjected to discrimination, violence, and structural inequality, and their realities have too often been treated as secondary within broader rights-based conversations. Feminism argues that women’s experiences are not merely a subset of “human experience” in the abstract, but a distinct and essential dimension of it, shaped by gender-based harm layered on top of injustices that may also affect other groups for different reasons.

Moreover, feminism is not limited to advocating for women’s legal rights; it also seeks to challenge the underlying societal norms and power structures that perpetuate inequality. Feminism aims to dismantle patriarchal systems that have historically marginalized women and to build a more just and equitable society – an effort that requires centering women’s perspectives, questioning entrenched hierarchies, and, at times, pursuing far-reaching structural change rather than incremental reform.

Another reason feminism is sometimes foregrounded is that human rights organizations have, in practice, often failed to account for the specific ways in which gender shapes women’s experiences. Many human rights approaches emphasize individual rights and freedoms, while paying less attention to collective, structural, and social forces that constrain women’s lives. For instance, an organization may affirm the right to education, yet overlook how gender-based violence, discrimination, or restrictive social norms systematically deprive girls and women of educational opportunities, even when that right exists on paper.

By contrast, feminism emphasizes that women’s lives are shaped by the interaction of multiple forces, including gender, race, social class, and other forms of identity and power. Feminist analysis, therefore, seeks to address root causes, not only visible outcomes, and to do so through an integrated approach that recognizes overlapping and intersecting forms of oppression.

In parallel, critics argue that prioritizing feminism can sometimes risk overlooking the suffering of other marginalized groups or failing to represent the full diversity of women’s experiences. Some contend that certain strands of feminism have been exclusionary, marginalizing the realities of women of color, women with disabilities, and other groups. Intersectional feminism, however – an intellectual framework developed in response to such gaps – holds that women’s experiences are shaped by multiple, simultaneous forms of oppression, including racism, ableism, class discrimination, and more.

In that sense, intersectional feminism seeks to broaden feminism’s scope by amplifying the voices of women who face layered forms of marginalization, including women of color, women with disabilities, and women from low-income backgrounds. Others argue that feminism can at times become overly narrow, focusing heavily on individual rights claims rather than the deeper systemic reforms needed to confront entrenched inequality and injustice.

Yet these criticisms do not necessarily mean feminism is incompatible with human rights. Instead, they highlight the need for a more precise, inclusive, and holistic feminist approach – one that recognizes the complexity of women’s realities and the multiple, overlapping forms of injustice they face. When these complexities are taken seriously, feminism can function as a powerful tool for advancing human rights, challenging the norms and structures that sustain inequality, and pushing societies toward greater justice and equity.

Ultimately, the question of why feminism is sometimes given priority at the expense of human rights is itself complex, with multiple valid perspectives.

Human rights frameworks remain essential for defending the dignity and rights of all people, but feminism persists as a focused movement because women’s experiences were historically excluded or treated as peripheral, and because gender-based oppression operates through specific mechanisms that require dedicated attention. By centering women’s distinctive experiences and perspectives, while also confronting the broader social systems that perpetuate inequality, feminism can strengthen rather than undermine the human rights project and contribute to building a more just and equitable society. – Sahar Bn Ali

Saudi Arabia’s approach to Yemen

Asharq Al-Awsat, London, January 25

The recent transformations in the Yemeni arena place us before a revealing moment that cannot be read merely as a temporary tactical divergence among the actors involved in Yemen, especially those without direct border contact, but must instead be understood transparently as a structural clash between two competing geopolitical visions.

On one side stands a logic that bets on acquiring territory along the coasts and ports as gateways to influence and power; a logic inspired by the literature of “naval power” formulated by the American admiral and historian Alfred Mahan.

On the other side, a vision more closely grounded in geography, history, and identity has crystallized, drawing on Halford Mackinder’s concept of “land power,” through which Yemen is viewed as a deep and integral extension of the Arabian Peninsula – and its unique history, identity, and culture that have been shaped over decades and reflected in its population, regional composition, and organic relationship with its neighbors, as foremost among them Saudi Arabia.

Accordingly, the outcome between the two logics is clear: Those who wager solely on ports lose, while those who invest in land, identity, and development ultimately prevail, no matter how long it takes.

Historically, Yemen’s coasts along the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea have tempted regional powers seeking rapid maritime influence by controlling corridors and chokepoints, yet this approach has repeatedly collided with a stubborn Yemeni reality – a complex society, deeply rooted tribes, a long political memory, and a resilient identity that cannot be hijacked by a minority, regardless of the resources poured into slogans, fallacies, or attempts to exploit moments of vacuum and external tutelage.

For Riyadh, the approach has been clear, open, and publicly articulated to the international community: Yemen constitutes a direct geographical and historical extension of Arabian Peninsula security, and the 1,200-kilometer border between the two countries is not merely a line on a map but a shared social and cultural space, making any internal turmoil in Yemen an immediate threat to Saudi national security.

Here, the regional logic of the “heartland” becomes evident: Those who seriously engage with the situation in Yemen must prioritize the interests of its people by invoking an inclusive national entity and by managing Yemen’s diversity through dialogue and fair representation. Whoever does so holds the keys to genuine stability, however long the process may take.

The past few years have shown that betting on armed local forces or externally driven separatist projects may deliver quick tactical gains but ultimately deepens fragmentation and entrenches lasting chaos, a reality Riyadh recognized early on, gradually redefining its intervention around supporting the national state rather than hybrid entities.

In this light, the recent Saudi shift toward directly engaging with the situation in Yemen and imposing the logic of “state vs agents” can be understood not as a mere adjustment of policy tools but as a restoration of a correct geographical reading. Yemen, in this vision, is not governed through islands and ports but through legitimacy capable of engaging the interior and representing it before international institutions.

The Saudi approach, by virtue of geography, positions the kingdom as a central actor with a development-oriented project that does not seek hegemony but rather aims to anchor stability in the region; refusing to treat Yemen as a narrow file or a collection of isolated points of influence, since such pragmatic yet unrealistic thinking would only generate further chaos.

Instead, it has chosen to approach Yemen as an integrated sovereign space requiring state reconstruction, institutional strengthening, opportunities for dialogue among its components, and an equal distance between them to prevent fragmentation into cantons.

Today, after events have unfolded as they have, Saudi Arabia has firmly recognized and addressed the “coast trap” in the Yemeni approach, a trap akin to privileging one sectarian component over another. Despite its deep wounds, Yemen retains the elements of genuine renewal whenever the logic of the state is reconsidered and liberated from the logic of partial wills and fragmented projects, and it is here that the Saudi vision of stability and unity gains significance. This vision does not view Yemen as a burden, an arena for influence, or an opportunity for exploitation, but as a partner capable of restoring its own well-being when its people, without discrimination, are given the chance to decide their future away from the chaos of weapons and the sin of division. – Youssef al Dini

Translated by Asaf Zilberfarb. All assertions, opinions, facts, and information presented in these articles are the sole responsibility of their respective authors and are not necessarily those of The Media Line, which assumes no responsibility for their content.