Something I’ve noticed quite often is how people pay for internet speed that they never realistically experience. Most of the time, it’s not because the ISP is malicious, but because their setup is somehow working against itself. So, even though the network technically works — devices connect, pages load — they experience inconsistent latency, dropped calls, and random slowdowns.

It’s possible to tweak settings for marginal gains, but let me focus more on the foundational mistakes that determine how your home network behaves.

Treating the router as “the network”

Why all-in-one routers hide architectural problems instead of solving them

It’s not uncommon to think of the router as the network. This is why, as long as it’s powered on and the internet works, you assume everything behind it is okay. In reality, you may be placing too much responsibility on an underpowered device.

Most consumer routers, all at once, are doing the job of routing, NAT, firewalling, DHCP, DNS forwarding, and switching. On top of all this, they also act as a Wi-Fi access point. The problem is that every one of these tasks is constantly competing for memory and CPU. Under light use, there are no problems, but in the real world, you are probably connected to several devices, performing uploads, making video calls, and doing backups. These activities cause latency spikes, and your packet queues grow. Nothing alerts you, since the network doesn’t outright break.

Buying more expensive hardware may not automatically fix it. However, you can manage this problem better by recognizing roles. Your best bet to change how your network behaves under stress is to switch to a router with better queue management. A $70 router running OpenWrt with SQM will outperform a $300 consumer router in latency-sensitive tasks (gaming, video calls).

Letting ISP defaults define your network’s behavior

The network you didn’t design is the one you keep debugging

Credit: Gavin Phillips / MakeUseOf

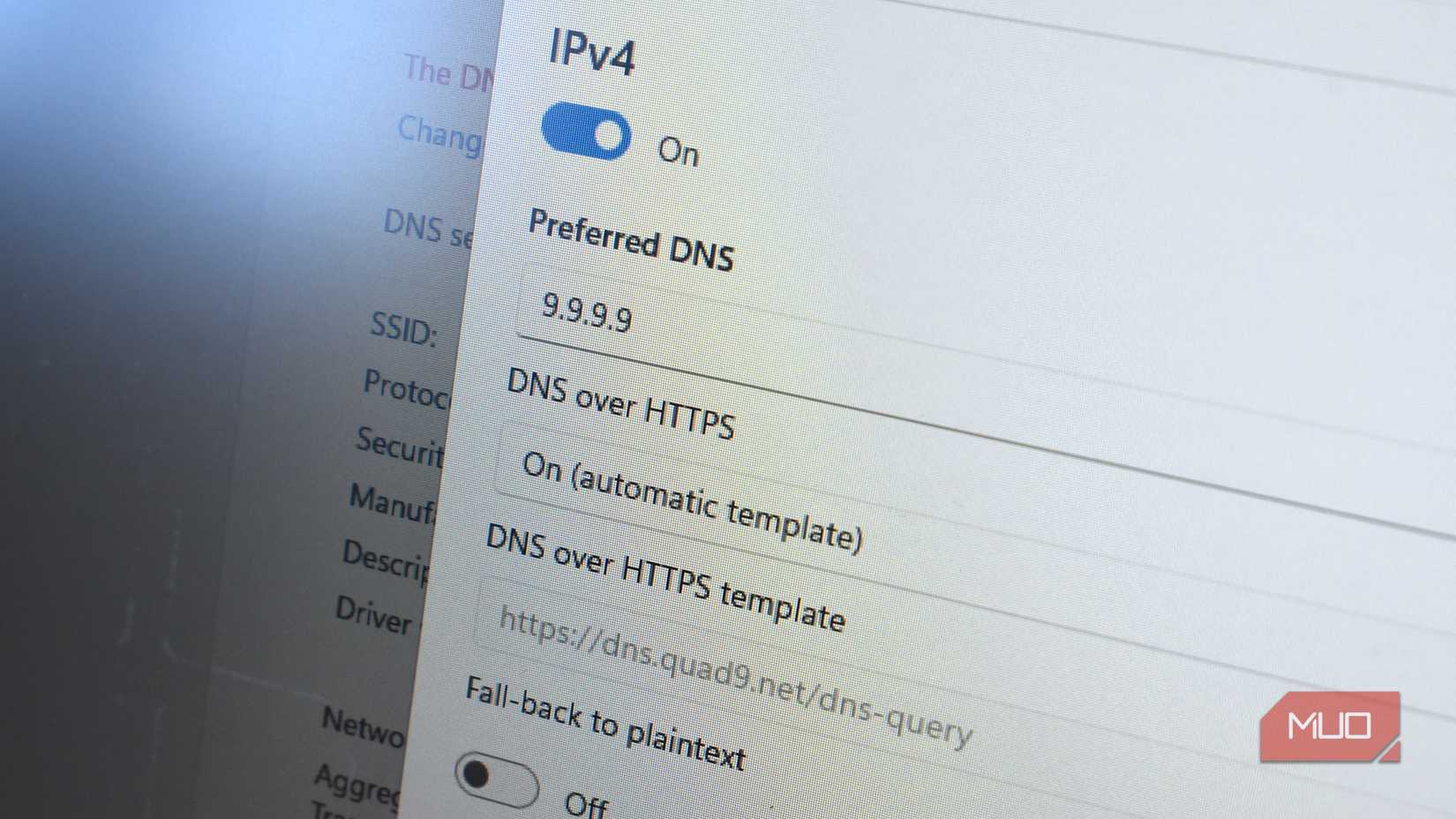

If you use ISP-provided gateways, you should understand that their design aims at reducing support calls, not necessarily delivering the best possible network behavior. For them, the goal is to prioritize compatibility, aggressive buffering, and locked-down configurations. In some cases, this is done at the expense of latency and control.

I’ve often seen people add a router behind the ISP gateway. They even do this without disabling routing on the gateway itself. This eventually leads to routing decisions that are hard to understand, unpredictable port behavior, and double NAT. You may not notice any problems, but something slightly complex, like introducing a VPN, remote access, or gaming servers, will cause real network problems.

This is where bridge mode, as misunderstood as it may be, makes sense. If you use it correctly, it shifts the firewall responsibility to your router and eliminates an extra layer of buffering/NAT. Your network doesn’t automatically become faster because you reclaim control from the ISP, but it’s predictable enough to allow you to diagnose network problems.

Obsessing over download speed while ignoring how networks actually move data

Gigabit plans don’t fail, expectations do

Afam Onyimadu / MUO

I’ve seen people upgrade from 300Mbps to gigabit internet and end up complaining about how slow everything still feels. What they don’t realize is that raw download speed is only one metric for observing how data moves. In fact, in most modern homes, latency, packet loss, and upload capacity are more important factors.

Your downloads depend on uploads. Various elements, including TCP acknowledgments, video call audio, cloud backups, and smart devices, compete for upstream bandwidth. If it becomes saturated, even your downloads start to stutter. Since most speed tests are short and optimized for a single connection, they may not pick this up.

Protocol overhead is another factor. Your devices may have to take turns transmitting because a single TCP flow on a 1Gbps wired link often achieves about 940Mbps, while Wi‑Fi is effectively half‑duplex (cannot transmit and receive simultaneously). Here, faster download speeds aren’t the fix. The real upgrade is proper queue management and, when applicable, eliminating the upload problem with a symmetrical fiber connection.

Treating Wi-Fi coverage as a signal-strength problem

More bars often mean a worse network

It’s common to see people naively chasing signal strength. So, if a room has weak Wi-Fi, they start seeking better placement or more power.

The reality is that airtime and signal quality affect Wi-Fi performance, maybe even more than raw strength. Even though wide channels are appealing, they stand a higher chance of overlapping with neighboring networks, making them more vulnerable to interference. This forces repeated re-transmissions and dilutes airtime efficiency.

In some homes, mesh systems are helpful, but they come with their own tradeoffs, which are more pronounced if they rely on wireless backhaul. Using a wired access point typically outperforms an expensive mesh setup. So, rather than asking how strong a signal is, ask how clean the airtime is. I mapped 2.4GHz vs 5GHz Wi-Fi, and the results proved how a strong signal can be misleading.

Building a flat network in the name of simplicity

One subnet feels easy until everything starts misbehaving

A flat network may feel intuitive since every device can directly communicate with every other device, with no elements needing special configuration. The real problem is that this simplicity doesn’t scale, not even in a small home with several smart devices.

The constant background traffic, broadcasts, and discovery chatter that IoT devices generate is enough to affect the entire network in a flat setup. If a device is compromised or misconfigured, it spreads to everything else. In the end, what you end up with is a performance and stability issue.

In practice, segmentation shouldn’t be complex. You can reduce broadcast noise and limit blast radius with basic VLAN separation for IoT and guest devices. You should, however, not wait until there is a problem before you introduce structure, because it’s far harder to retrofit segmentation into a messy network than to plan for it early.

Running a network with no visibility and no history

Rebooting isn’t troubleshooting

Credit: Brady Snyder / MakeUseOf

Rebooting is the default response when there’s a network problem. It’s effective for certain issues, but you really never learn much from a reboot. As long as you don’t have visibility, problems will continue to feel random.

Most issues like latency spikes, packet loss, and roaming failures leave behind traces if your router supports adequate logging, and you’ve enabled it. But if you’re not looking, you won’t find them. You learn to approach problems differently when you do basic logging, simple monitoring, or review historical graphs. This way, rather than guessing, you’re correlating events and seeing patterns.

I learned much more from observing my network than from buying new gear. Observation equipped me with context and made fixes more deliberate.

Your home network works. That’s why it keeps failing you.

Bad hardware or slow internet doesn’t account for most of the home networking problems you face. These problems come from assumptions you made early and never revisited.

Setting up the perfect network for your home devices means making a deliberate effort to ensure it’s built well from scratch. This way, performance is predictable, and even problems are explainable.