This systematic review included twelve primary observational studies consisting of both cross-sectional studies (66.67%) and cohort studies (33.33%). These were included in the review and were published between 2014 to 2025. It includes participants in their late adolescence and adulthood. The review focused on the correlation between childhood abuse and the origin of psychiatric disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder, but overall, the studies also highlighted depression, anxiety, polydrug use, and suicide attempts as other concerning findings. Various ACEs were considered culprits for the precipitation and development of these mental health disorders. The ACEs included in the selected studies according to the criteria were: (a) Sexual abuse, (b) Emotional abuse, (c) Physical abuse, (d) Emotional neglect, (e) Physical neglect, (f) Witness to intimate partner violence, (g) household dysfunction, (h) perceived discrimination, (i) historical loss, (j) community violence, (k) maltreatment, (l) parent psychopathology, (m) low adversity.

The literature focuses on the association of individuals who experienced childhood maltreatment and later developed post-traumatic stress disorder. An epidemiological study conducted by WHO proved a positive association among physical, and sexual abuse, parent psychopathology, neglect, and the odds of developing PTSD (OR = 1.8) after experiencing trauma [13]. It concludes that parent psychopathology and child maltreatment emerged as a significant risk factors for PTSD and shines light on the age at which trauma is experienced, childhood-adolescence and early-middle adulthood were found to have a stronger effect on the development of PTSD than latter-middle age [13]. This finding reflects that the development of PTSD deteriorates with age which suggests the increase in protective incidents with age, this can also be explained by recall bias, that as age proceeds the memory of trauma fades [13]. Furthermore, inaccuracies may have occurred when PTSD was assessed using a standardized interview as opposed to a clinician-administered assessment [13]. It was observed that physical and sexual abuse were most likely related to PTSD, depression, and anxiety [14, 18, 24]. Adams et al. conclude that even though there is no significant correlation between the duration and severity of abuse with mental health, the onset in early adolescence predisposes more females to develop PTSD as compared to males [18]. Lee et al. specifically found that community violence and maltreatment increased the odds of PTSD as compared to low adversity [14]. Breslau studied the severity of maltreatment, especially in the first ten years of life, severe abuse increased the risk of posttraumatic stress by (OR = 2.64, 95% CI (1.16–6.0) concerning moderate neglect or no abuse [24].

A birth cohort of 1037 followed up to 38 years of age in New Zealand observed that the physical and sexual abuse recalled by the adults, which they faced as a child raised the possibility of bias as they are influenced by adult viewpoints and experiences related to trauma and PTSD later in life [24]. The sample’s geographic limitations and—more significantly—the range of ages of the adults during the years that data was examined place restrictions on the findings’ generalizability [24]. Mental health correlations after witnessing IPV can be a difficult event, and each child is affected differently; some develop anxiety, PTSD, and depression, and some resort to polydrug use or even suicidal attempts [20, 21]. Brockie et al. concluded that children who witnessed IPV developed PTSD (OR = 2.96, p = < 0.001), some used substances (OR = 5.3, p = < 0.001) in their adult life; children who were physically abused later were diagnosed with depressive symptoms (OR = 3.68, p = < 0.001), some of them also tried to attempt suicide (OR = 2.90, p = < 0.001) [34]. They also explored specific types of abuse (historical loss and discrimination) which showed a strong correlation with mental health. Still, the actual incidence of child abuse has likely been understated due to the use of judicially determined cases [20]. Kisely et al. is a prospective study where 3778 mothers and children were included, and 4.5% (n = 171) children suffered from maltreatment. The most prevalent one was emotional abuse (n = 91), other abuse included physical and emotional neglect, historical loss, and discrimination. [21] It conducted CIDI Auto (Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Auto version) to diagnose psychiatric disorders at 12 months and over a lifetime, PTSD was noted (4% (n = 111) and 6% (n = 161)) to have a strong association with childhood trauma [21].

Compared to [17, 21] presented a retrospective study of PTSD with early developmental trauma (n = 17), and compared them with health control (n = 31). Although no statistically significant data was extracted, certain findings were essential to consider [21, 24]. Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse was between 6 and 11 years of age, emotional abuse was more seen in people who developed PTSD in their adulthood than in children who faced physical and sexual abuse [17, 21]. This study also evaluated the gender and the role of the physical, sexual, and emotional abuser which was found to be male caregiver, outsider male, and female caregiver respectively [17, 21]. Whereas [18] concluded that females when maltreated at an earlier age have a higher propensity to develop PTSD and anxiety. These results are eye-openers and can aid in changing the current preventive measures.

Macpherson et al. found a strong connection between childhood maltreatment and mental disorders, with PTSD being most closely correlated (HR 1.68, 95% CI: 1.27–2.20) [23]. Participants who frequently binge drank or made few social contacts were more likely to exhibit this connection [23]. The possible mental health effects of abuse were evaluated using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), and it was discovered that these effects persisted 20–70 years after the traumatic incident, even in people who had no prior history of mental problems in their early adult years [23]. In a separate study, Chen et al. included trauma-exposed adults who sought treatment at an emergency department following a traumatic event [16]. In each category of reported maltreatment, the participants, who were 33.1 years old on average, claimed varied degrees of abuse throughout their childhood [16]. Three months after their traumatic event, the criteria for PTSD diagnosis was met by 27.8% of participants based on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), and dispositional optimism was found to mediate the relation between PTSD and childhood maltreatment [16].

Adams J. et al. concluded that the initiation of physical abuse during childhood increased odds of all forms of psychopathology (β = 0.07 for anxiety, β = 0.19 for PTSD, and β = 0.13 for depression, all p < 0.05) and the commencement of physical abuse during childhood and teenage years was linked to a higher number of PTSD symptoms (β = 0.08 and β = 0.11, p < 0.05, respectively), without affecting other kinds of psychopathology [18]. Additionally, there was a clear correlation between the onset of sexual abuse in adolescence and childhood, and higher levels of symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD [18, 19].

Lee H. Et al. identified four heterogeneous ACE classes, of these, the “child maltreatment” class had a greater probability of adult PTSD, depression, and anxiety than the “low adversity” class [14]. A major toxic threat that can be associated with PTSD is community violence exposure, and the effects of various forms of ACEs on young adults’ mental health outcomes vary [14, 25]. Kim M. et al. used self-report questionnaires and organized clinical interviews to assess the severity of PTSD concluding that childhood abuse experiences were linked to heightened lifetime PTSD symptoms, with the influence of low resilience levels and the adoption of dysfunctional coping strategies mediating this association [15]. Rachel A. Maja, et al. assessed participants for ACEs and post-traumatic stress symptoms and presented that adverse PTSD symptoms and worse executive functions related to oneself were connected to an increased number of ACEs that were documented [18].

ACEs have a positive correlation to the development of PTSD after trauma exposure in adults, which was measured at 2 weeks (p < 0.01) and 3 months (p < 0.001) following a traumatic exposure [22]. This is a unique cohort study that compares and contrasts thalamic nuclei and their volume to the exposure to childhood trauma, the volume of 22 nuclei (n = 50 nuclei) in the PTSD group was found to be decreased as compared to the non-PTSD group [22]. Points out that the inverse proportionality is only seen in 3 months post-trauma and not in 2 weeks, which signifies several factors that influence and reduce the thalamic volume [22].

Limitations

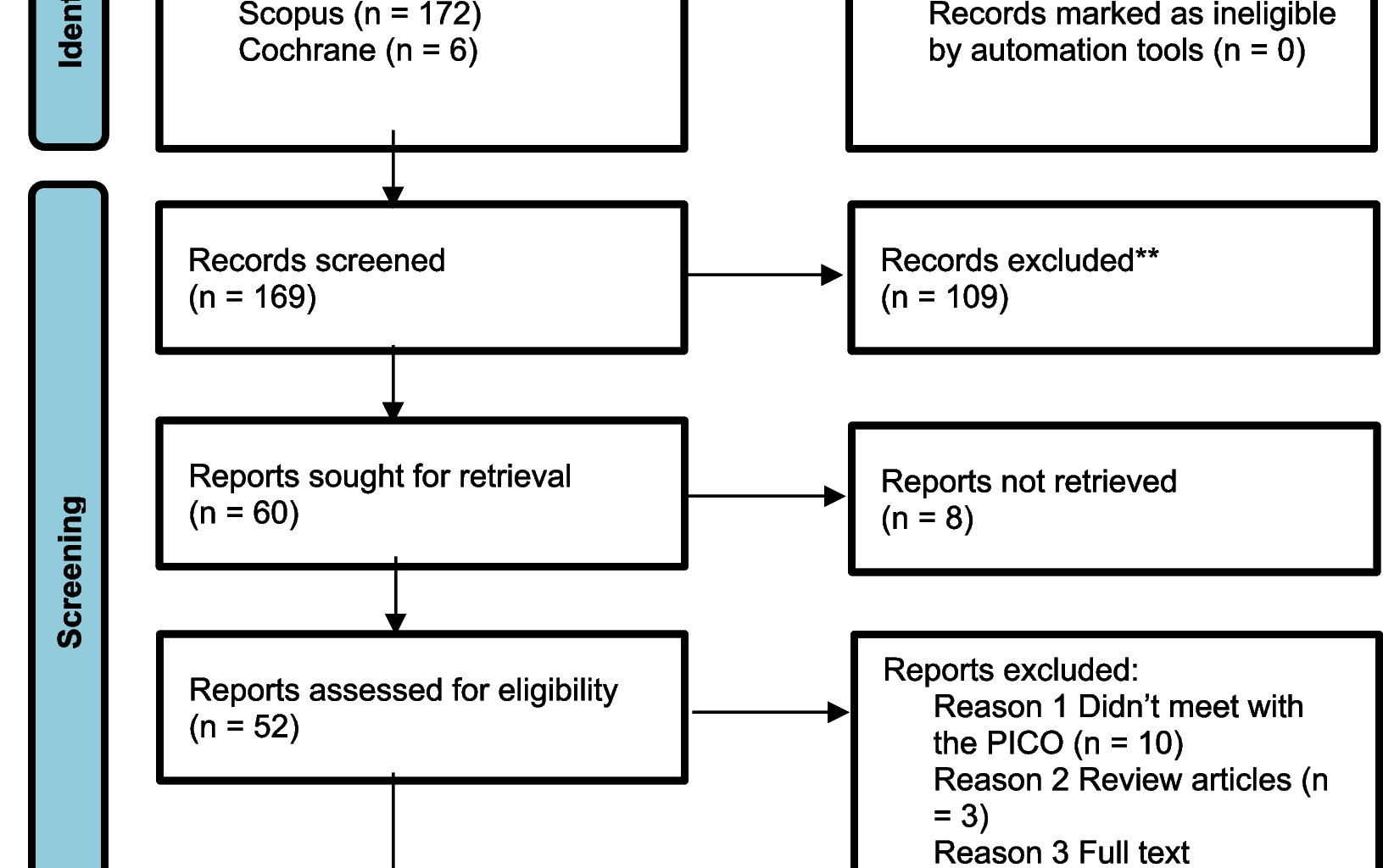

It is essential to recognize the limitations of these studies. Recall bias in people who do not develop PTSD symptoms is possible, as they might not remember the extent of trauma. Location restrictions and sample size limits also affect how broadly the results can be applied. Some articles were excluded because they were inaccessible or were written in languages other than English. Furthermore, biases should be carefully considered when interpreting data, as there were no randomized controlled trials in the finalized articles.

Subsequent investigations should address these constraints while examining innovative interventions and preventive measures. To lessen the long-term effects of ACEs on mental health, we may create more effective therapies using a holistic approach that considers both environmental and individual aspects.