We’re living in a moment where the news and information ecosystem is more fragmented than it has ever been. It’s entirely possible for three people living in the same household to be operating with three completely different perceived realities, simply because of where they get their information. One person is watching traditional news. Another is scrolling social media. A third is searching online or asking an AI tool. They’re all exposed to different facts, different frames, and different levels of credibility.

And nowhere is that fragmentation more consequential than when it comes to health.

Earlier today, I presented at an Empire Club event in Ottawa organized by the Canadian Medical Association.

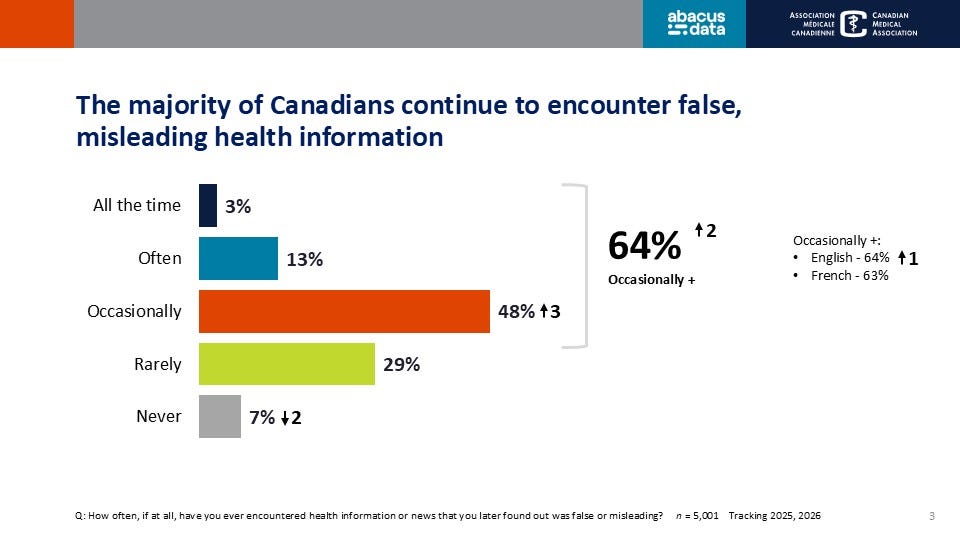

In our third annual wave of research exploring the health and health system information ecosystem with the CMA, we find that exposure to false or misleading health information has become a near-universal experience. Nearly two-thirds of Canadians say they encounter health information or news that they later learn is false or misleading at least occasionally. That level has barely moved since last year and is up meaningfully from 2024. This is no longer a fringe issue. It’s simply part of the background noise of modern life.

What’s striking is how consistent this is across age groups. Boomers are slightly less likely to report encountering misinformation, but among Gen Z, Millennials, and Gen X the numbers have remained remarkably stable. The noise is everywhere and most Canadians, regardless of age, are hearing it.

At the same time, trust is shifting. Trust in institutions that have traditionally been authoritative sources of health information is declining. Trust in social media is also declining. And yet trust in personal networks is holding, and in some cases increasing. Trust in physicians and family remains comparatively strong, while trust in news organizations, both Canadian and American, has dropped sharply over the past year.

This matters because Canadians are still actively searching for information. Nearly nine in ten go online for health and health care information, whether it’s symptoms, treatment options, chronic condition management, or how to access care.

And when we ask why they go online, the answer isn’t accuracy. It’s speed. It’s convenience. It’s availability when a professional isn’t accessible. The information ecosystem is filling gaps left by a strained health care system.

Artificial intelligence now sits right at the centre of this tension. Only about a quarter of Canadians trust AI to provide accurate health or health system information. And yet many are using it anyway, especially younger Canadians. AI tools are becoming a first stop for advice and guidance, even as trust remains low.

That gap between use and trust matters, because the consequences are real. People who follow health advice from AI are far more likely to report negative health impacts than those who do not.

Health misinformation isn’t just abstract. It creates confusion about how to take care of oneself. It increases anxiety. It delays people from seeking appropriate care. It strains relationships. And critically, it challenges trust in health professionals.

Over time, encountering inaccurate information pushes people away from the health care system itself, making them more skeptical not just of what they see online, but of advice from providers they should be able to rely on.

And yet the story doesn’t end there. Most Canadians say that having better access to good health information helps them be better patients. And an overwhelming majority continue to trust physicians to help them navigate this complex, often overwhelming information environment.

The challenge ahead isn’t just about fighting misinformation. It’s about rebuilding confidence in an environment defined by fragmentation, speed, and uncertainty.

Canadians are telling us they want guidance, not noise.

They want help navigating, not more information to sift through.

I ended my presentation with a thought about the bigger picture. I said,

The challenge ahead isn’t just about fighting misinformation. It’s about rebuilding confidence in an environment defined by fragmentation, speed, and uncertainty.

Canadians are telling us they want guidance, not noise.

They want help navigating, not more information to sift through.

In this world, trusted voices don’t just matter – they anchor people back to the health care system.

The opportunity here is to meet people where they are, acknowledge how they actually search for information, and reinforce trust at the moments when it matters most.

I hope you’ll review the research in more detail and share with those you think will find it useful.