A near tripling of the electrical power available to drivers in F1 2026 has introduced an all-new element to driving, with drivers having to manage their speed through corners to conserve the available battery boost.

For this season, cars boast 350kW of electrical energy per lap, up from 120kW last year, creating a unique and counter-intuitive style of racing: to go fast, drivers must, at points, go slow.

Bahrain data reveals how energy strategy is reshaping performance

Want more PlanetF1.com coverage? Add us as a preferred source on Google for news you can trust.

Fernando Alonso, never one to shy away from a dry quip, offered a characteristically sharp assessment, suggesting that even Aston Martin’s head chef could drive the car in its current state.

What Fernando sought to spotlight is the sheer level of electrical system intervention in the racing. This became the dominant talking point during the first official test in Bahrain.

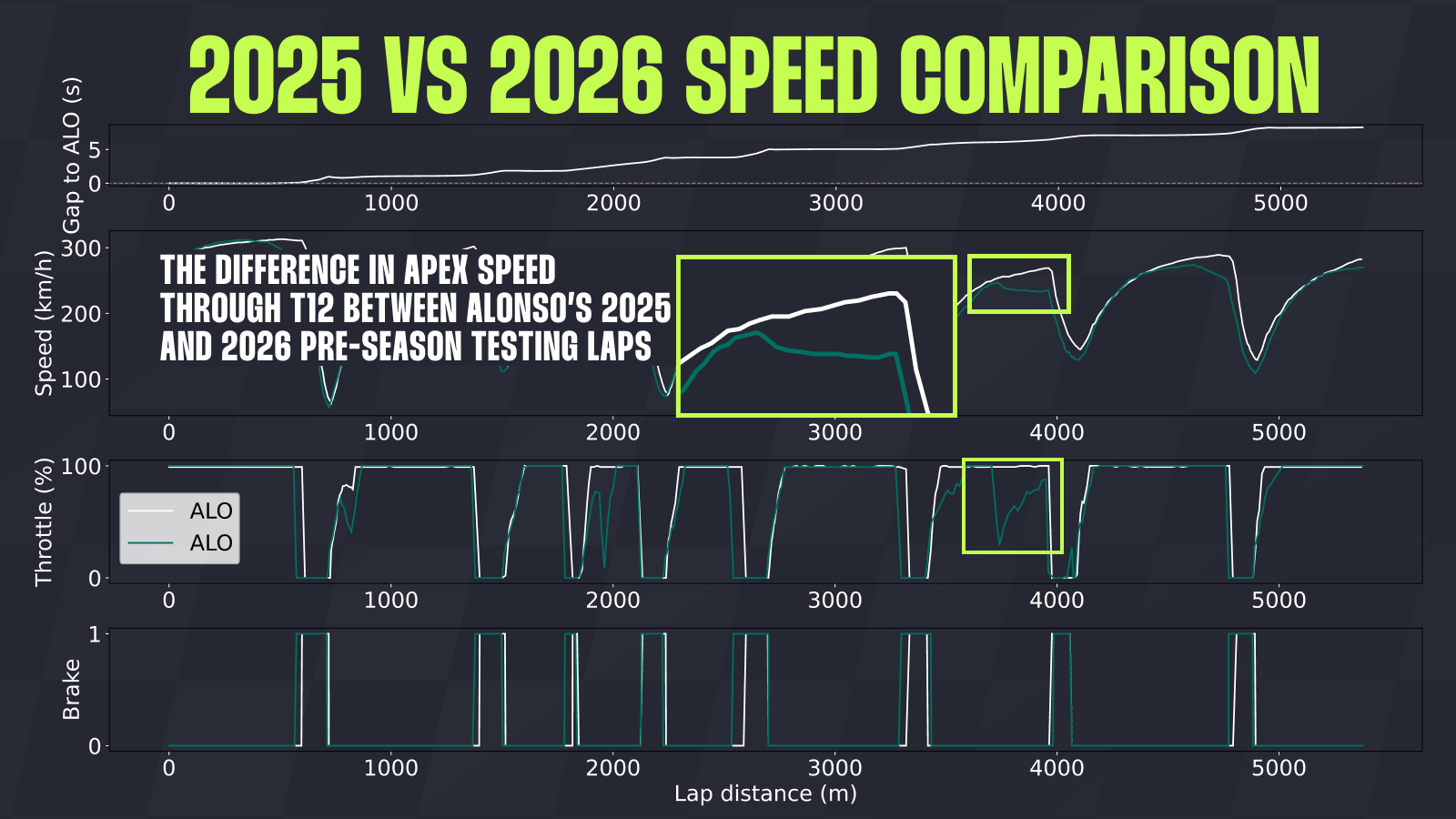

The Aston Martin veteran drew specific attention to Turn 12 in Bahrain, claiming that his apex speed through this corner during these tests is a staggering 50 km/h lower than what he has been used to in previous years.

And this figure is absolutely spot on with the graph below revealing the sheer scale of the speed deficit. In this example, we have compared his fastest lap from the 2025 pre-season test against this year’s running in Bahrain.

In this year’s lap, he wasn’t “flat out” through the apex of Turn 12 as he was able to be last year. Judging by his comments, the Aston Martin team opted not to deploy maximum engine power in this specific corner, so as not to squander precious energy that could be better utilised elsewhere on the circuit.

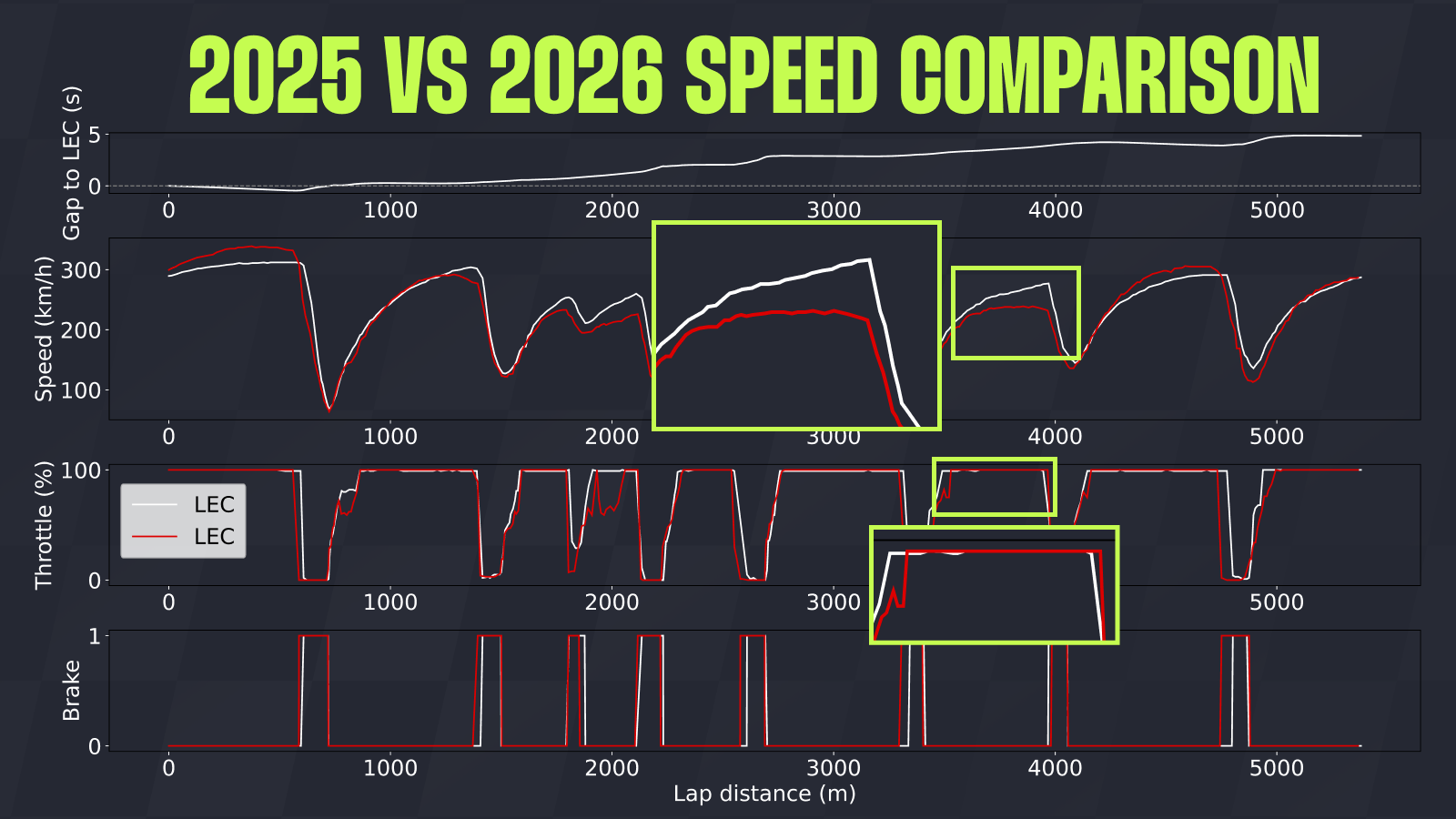

However, an even more drastic example can be found elsewhere. The graph below compares Charles Leclerc’s fastest laps from the 2025 and 2026 tests. In his case, he was flat out through Turn 12 in both scenarios, yet the difference in apex speed remains just as significant as it was for Alonso.

The new F1 2026 technical regulations allow for a “boost” of 8.5MJ of electrical energy per lap, usable anywhere on the track. The catch lies in the fact that the battery has a delivery capacity of only 4MJ per cycle, meaning it must be recharged thereafter.

This rule has prompted teams to test various strategies where everyone, Aston Martin included, is trying to find the optimal place, time, and, most importantly, method to actually recharge their batteries.

One such method is “clipping” or limiting the power the system delivers even when the driver is at full throttle.

The regulations allow for a negative ERS usage of up to -250kW at full throttle. Given the internal combustion engine produces around 400kW, the car can “steal” up to 250kW of that power to charge the battery. This leaves the driver with only a 150kW engine – a power figure quite easily found in a standard road car.

The graph below explains this phenomenon even more clearly:

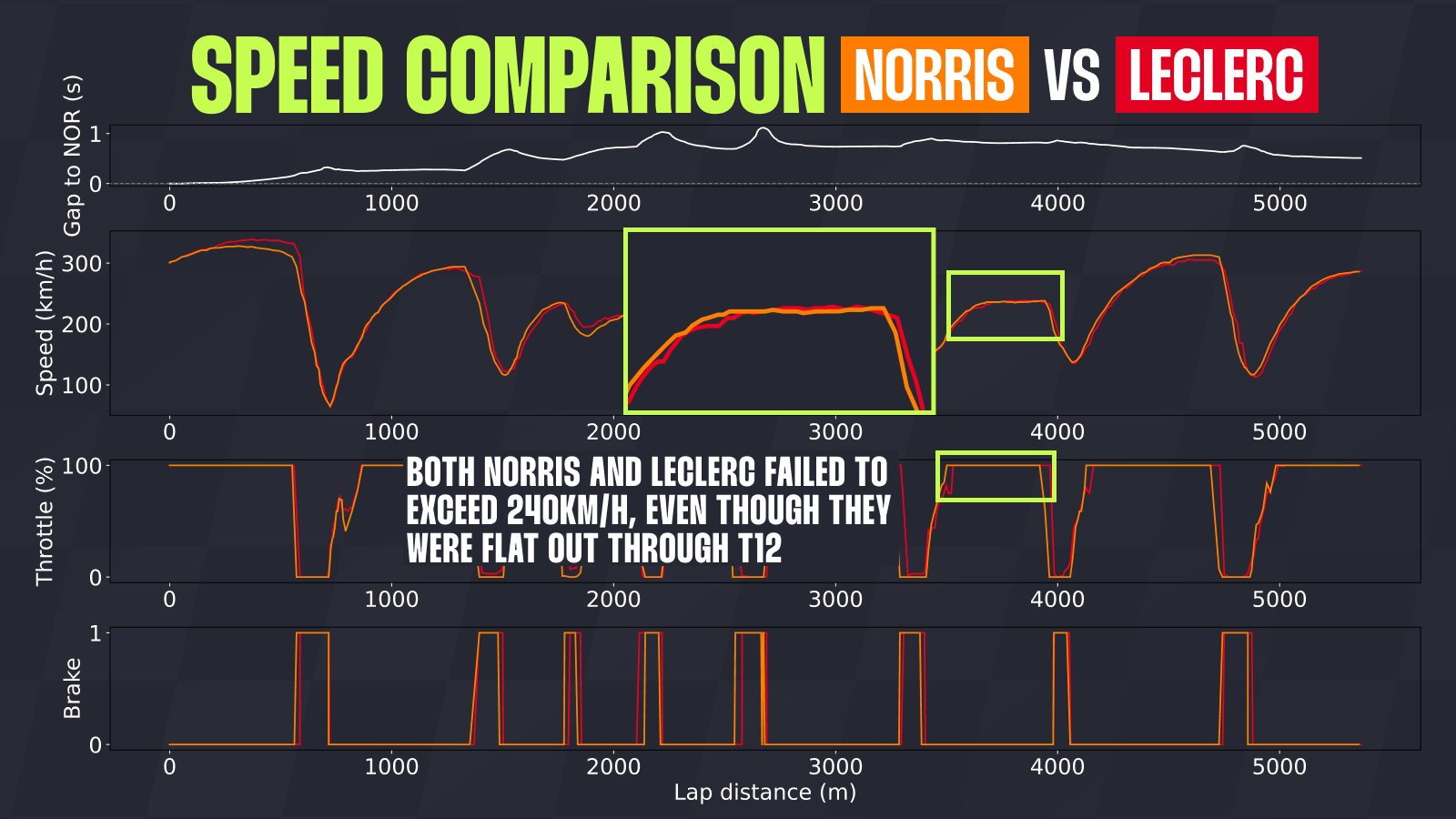

Leclerc and Lando Norris were the two fastest drivers during the second day of testing and, during their flying laps, had an identical data trace. Both were “flat” through a 300-metre section of T12, yet neither managed to exceed 240 km/h. It is crystal clear: even though they are at full throttle, their car speed remains constant throughout this entire period.

With the exception of Leclerc’s slightly higher speed on the start/finish straight and greater confidence through T6 and T7, their laps are remarkably similar.

Max Verstappen, the four-time champion, hasn’t hidden his dissatisfaction on the matter either, stating that while he loves driving “flat out,” this is not, in his view, the correct way to race.

As things currently stand, it’s hard not to agree with that sentiment. While technological advancement has brought much to the sport – notably, greater safety than ever before – the general consensus is that tech should never replace the driver and their raw ability behind the wheel.

The current feeling is that the new technical regulations, at times, push driver skill into the background, allowing the team and a pre-set system to do the heavy lifting instead. Turn 12 in Bahrain is the perfect case in point: we can have three different drivers flat-out through this section, but their speed will actually be dictated by a program the team mapped out beforehand – all for the sake of charging the battery as efficiently as possible.

What we can expect in the upcoming testing periods, and as the 2026 season progresses, are even more examples where the 2026 cars are either painfully slow or incredibly fast compared to the 2025 generation. It remains to be seen whether such a system will truly deliver better and more engaging racing on the track.

Want to be the first to know exclusive information from the F1 paddock? Join our broadcast channel on WhatsApp to get the scoop on the latest developments from our team of accredited journalists.

You can also subscribe to the PlanetF1 YouTube channel for exclusive features, hear from our paddock journalists with stories from the heart of Formula 1 and much more!

Read Next: Bahrain telemetry suggests Red Bull engine edge after Wolff claim