The Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is a league of teams playing women’s basketball, the fastest-growing sport in 2024, according to Forbes. The WNBA is ranked the fifth most popular professional sport in the U.S. due to high-profile, talented players such as Angel Reese, A’ja Wilson, Napheesa Collier, Caitlin Clark, Paige Bueckers and others who were drafted from top-ranked National Collegiate Athletic Association teams. The sports teams ahead of the WNBA are the all male National Basketball Association, National Football League, Major League Baseball and the National Hockey League.

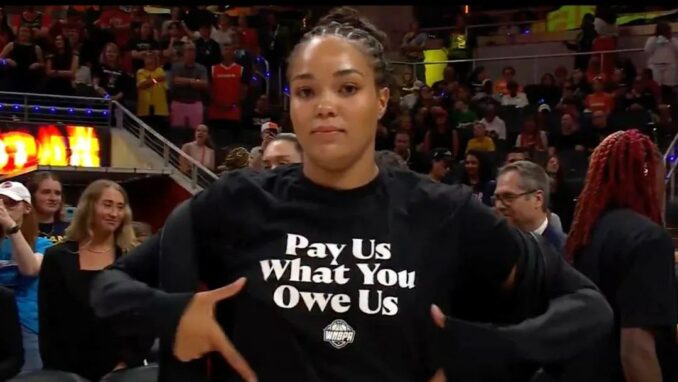

Minnesota Lynx player Napheesa Collier at All-Star Game, July 19, 2025.

WNBA regular season games are selling tickets to near capacity in arenas all over the country from New York to Indianapolis to Las Vegas making record-breaking profits for team owners.

Bloomberg News reported that the value of WNBA broadcast rights alone has mushroomed from zero in 2002 to roughly $60 million a year in the current deal, with that number set to jump upwards of $200 million as part of the combined deal with the NBA. The total league revenue jumped from $102 million in 2019 to over $200 million in 2023. (Feb. 14, 2025)

One would surmise that with the enormous jump in popularity of the WNBA that players’ salaries would be commensurate with the increased revenue. But that is far from being the case.

The overall salaries of WNBA players, despite filling arenas and broadcasting more games during prime time, remain extremely low. WNBA players are making less than 10% of team revenue, a rather tiny figure for any professional organization, especially if it is male dominated. Sexism undoubtedly plays a dominant role in this case.

According to Market Watch, under the current CBA (collective bargaining agreement), “WNBA players only split 9.3% of total league revenue, which is much less than what athletes in other major sports leagues earn. NBA players in aggregate receive between 49% and 51% of basketball-related income, NFL players get 48% of all revenue and NHL players get 50% of revenue. Those revenue splits encapsulate money generated from broadcast TV deals, tickets, merchandise sales and licensing.” (Oct. 22, 2024)

The highest paid WNBA players make close to $242,000, while the lowest paid make under $70,000 annually. Compare this to the NBA, with the highest paid players averaging between $40-$50 million and the lowest paid making close to $2 million annually. Many WNBA players feel compelled to play for teams in Europe and elsewhere during their off season to generate more income for themselves and their families.

Players demand better pay and benefits

WNBA players are not seeking salaries that even come close to their NBA counterparts but are demanding what they see as their fair share in the form of higher pay and more benefits.

For this reason, WNBA players opted out of their current CBA agreement which expires at the end of the 2025 season, once contract negotiations broke down on July 17. The players have threatened to organize a walkout in October if they don’t get a bigger share of the revenue that their popularity, skills and talents bring to the game.

During this year’s WNBA All-Star Game (ASG) in Indianapolis on July 19, all of the players wore pre-game warmup shirts that bore the slogan “Pay Us What You Owe Us.” It was a splendid display of unity from all the players, no matter what team they were representing.

And when the WNBA commissioner, Cathy Engelbert (whose position represents the interest of the owners), began to announce the winner of the most valuable trophy to Napheesa Collier following the game, fans began to chant, “Pay them! Pay them!” to the point that Engelbert could hardly be heard. A great majority of WNBA fans are women, gender oppressed and working class and therefore are well aware of which side they are on.

WNBPA (Women’s National Basketball Players Association) president Nneka Ogwumike said after the ASG: “I’m just so inspired by the amount of players that showed up, the engagement that was there. That’s really what it’s all about. Because the more that happens, the more that we’re going to be able to get things done. I think today we’re going to be able to use this conversation to start rolling the ball on things.” (The Guardian, July 19)

The writer’s father, Isaac T. Moorehead, was head basketball coach for the Norfolk State University women’s basketball team in Norfolk, Virginia, that won a Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) championship during the 1980s.