Artificial intelligence is changing how some educators plan their lessons and think about assignments for students.

They’re contending with how to use it appropriately and ethically in their classrooms ahead of the school year, at a time when the Manitoba government and many school divisions haven’t finalized guidelines and policies on AI use.

These are questions that came up at a conference for education officials and teachers in Winnipeg this week, hosted by the University of Winnipeg, the University of Manitoba, and the Canadian Assessment for Learning Network.

The event explored concerns over academic integrity, cognitive skills, along with copyright and privacy issues while using AI detectors. It also questioned the ethics of teachers using those detectors to catch and punish students who may have produced original work, or using AI to help brainstorm and write report card comments.

Ontario researcher and teacher Myke Healy, who presented at the event, says AI use in schools is evolving but inconsistent.

“There’s a spectrum” in opinions on how to use it, from “I don’t want to use it at all [and] it should be banned” to “we have an absolute responsibility … for students to be able to understand these tools, because they’re going to be using it in the workforce,” said Healy, the assistant head of teaching and learning at Trinity College School.

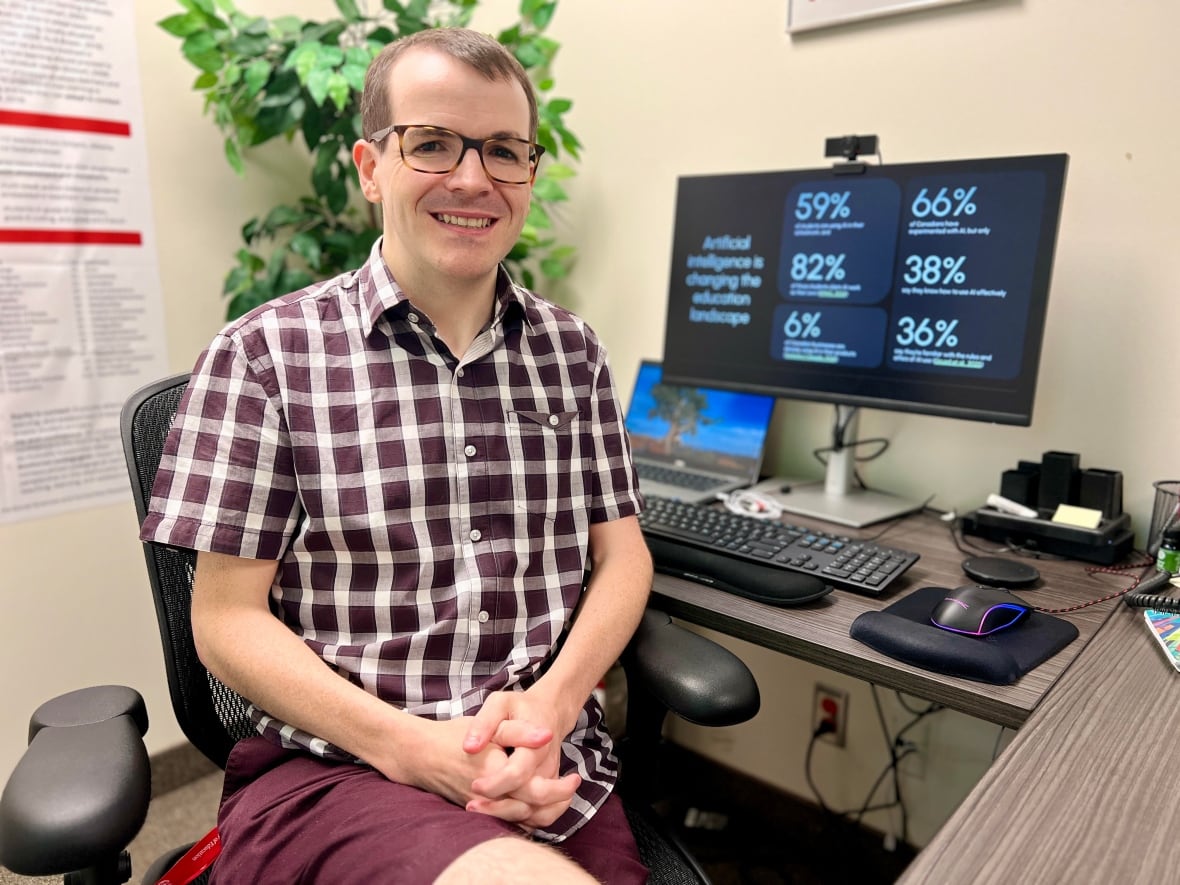

Educator and researcher Myke Healy of Ontario’s Trinity College School feels it’s important for educators to understand the power of AI tools. He says accurately distinguishing AI from authentic student work is as good as a ‘coin flip.’ (Jeff Stapleton/CBC)

As a doctoral student at the University of Calgary, he’s investigating how K-12 schools are adapting and fostering academic integrity in a reality, “where AI can do most, if not all student work.”

One of his concerns heading into the 2025-26 school year is the gap in how kids are already using generative AI platforms, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and how school systems are responding.

WATCH | Majority of students surveyed say AI use detrimental:

Are students leaning too much on AI in their work? Surveys say yes

Surveys suggest many students are using generative artificial intelligence in their work, with KPMG in Canada finding that nearly 70 per cent of students who use AI say they are not learning as much as a result.

Last October, a KPMG poll suggested 59 per cent of Canadian students surveyed used generative AI in their schoolwork, a 13 per cent increase over the year before. Of those students, 82 per cent admitted to claiming it as their own work.

“The fundamental challenge in education right now is that we need to assess student learning in a different way,” Healy said.

Schools may need to adapt to more conversation or demonstration models of assessment, so students can show what they’ve learned directly with an educator, he said.

University of Winnipeg assistant professor of education Michael Holden is looking into that, as well as how generative AI can play a role in learning while educators ensure learning remains at the heart of the process.

“We have to think about, ‘OK, are there ways that we can use AI to help the work that we’re doing with our students, and are there things that we need to be careful about?'” said Holden, who specializes in classroom assessment.

Michael Holden, an assistant professor of education at the University of Winnipeg, investigates how artificial intelligence can play a role in learning, while educators ensure learning remains at the heart of teaching. (Travis Golby/CBC)

Michael Holden, an assistant professor of education at the University of Winnipeg, investigates how artificial intelligence can play a role in learning, while educators ensure learning remains at the heart of teaching. (Travis Golby/CBC)

He says educators will need to identify the skill they’re targeting, whether it’s brainstorming or editing an essay, and make sure the assignment they’ve created still challenges the student and encourages them to do the learning.

“If an assignment is vulnerable to a student using an AI tool and just plugging the question in, getting an answer out, copying and pasting, that probably was never a particularly good assessment task.”

One way a high school English teacher could explore generative AI in their classroom is having students critique the output it produces, Holden said.

“You know that tool can write an essay for you. Can it write a good essay?… Does it make a good line of argument, or does it cite real examples?”

Healy’s advice is to have kids grasp the skills before guiding them through interactions with generative AI platforms that could take their work further.

New teacher Chloe Heidinger says she doesn’t plan on shying away from conversations about appropriate AI use with her students and using it to teach critical thinking skills. (Jeff Stapleton/CBC)

One of Holden’s former students, Chloe Heidinger, is heading into her first year of teaching in Winnipeg. She views generative AI platforms as mentorship tools.

She doesn’t plan on shying away from conversations with her students on how to use it appropriately and ethically, or using it to teach critical thinking skills.

Heidinger says the challenge will be having students interact with it rather than using it to produce content.

“For example, instead of saying, ‘Write me an essay on Romeo and Juliet,’ or say, ‘Edit my essay for me’ … saying, ‘I want to edit this for commas,'” or asking “‘how and why did you change it?’ And then that way they’re reading and they’re reflecting.”

Heidinger said she thinks English language arts classes will be especially challenged in the AI era and may need to lean on crafting assignments that are meaningful and personal to students.

“How can we encourage students to actually want to write and want to put in their own experiences and their own life experiences, rather than just have an AI generative tool produce content for them?”

AI guidelines, policies

Holden says in the meantime, many educators feel they’re being left to decide how to use AI on their own. He urges the province and its school divisions to develop policies and resources to support them.

CBC News contacted a number of Manitoba school divisions about whether they’re developing AI guidelines and policies. Most said they are, but some will not be finalized in time for the school year.

The Louis Riel School Division says it’s in the early stages of developing internal guidelines. River East Transcona School Division expects to develop guidelines too, to support AI use as an “educational and productivity tool.”

The Winnipeg School Division said it’s working with a consultant to understand how AI can be used responsibly to enhance teaching and support learning. It plans to present a draft of its policy to its board of trustees in early 2026, a WSD spokesperson said.

WATCH | Teachers, divisions mulling policies for AI in classrooms:

Educators consider appropriate, ethical AI use as policies develop

Artificial intelligence is changing how some educators plan their lessons and think about assignments for students. They’re contending with how to use generative AI appropriately and ethically in their classrooms ahead of the school year. Manitoba’s education minister says the province is developing “clear guidelines” on AI use.

The St. James-Assiniboia School Division developed an AI strategy last year that was shared with staff in May, the division’s director of information technology, Al Stechishin, told CBC News in an emailed statement.

Its guidelines detailed how it could be applied to brainstorming, feedback and tutoring, among others, while emphasizing its use should complement, but not replace students’ work.

In a written statement, Education Minister Tracy Schmidt said the province is also developing “clear guidelines about the use of artificial intelligence in schools,” and says resources for teachers are available through some educational institutions.

Holden says without policies, there’s a risk educators and students won’t be supported equally.

“Either that will mean that a teacher or a student uses a tool inappropriately to do something they shouldn’t have done, or it might mean they avoid using it at all, and they end up putting themselves or their peers at a disadvantage,” he said.

“Students have access to these tools, so we have to teach them how to use them well, when it’s appropriate to use them, when it’s not appropriate to use them.”