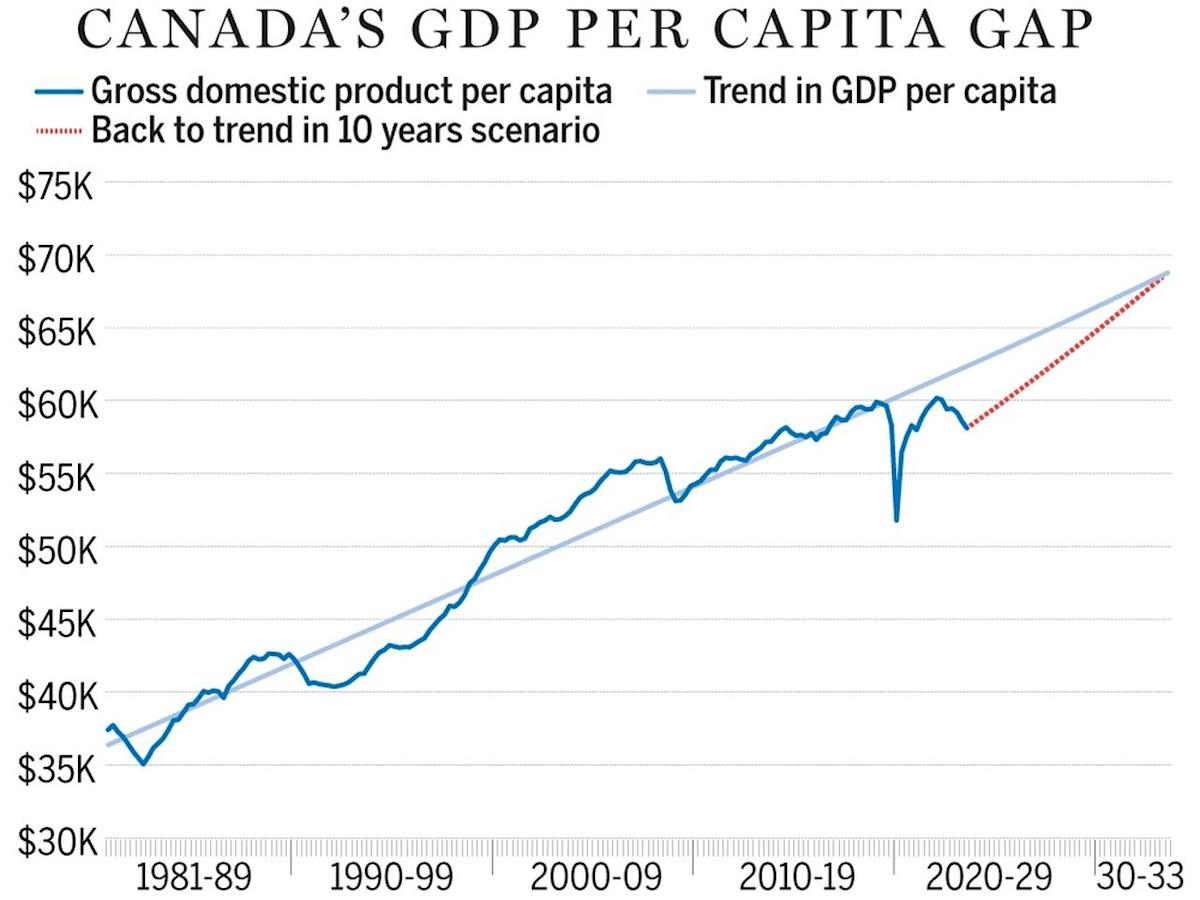

Source: Statistics Canada (Credit: Gigi Suhanic/Financial Post)

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, citizens of Canada and the world were advised not to be overly stressed by the short-term economic impacts. We were told that the governing authorities had the ability — through monetary policy, government spending and careful management of the pandemic — to overcome the unpleasant economic recession and social impacts to produce a swift return to normal growth and prosperity.

One example from the Canadian archive of such claims is former finance minister Chrystia Freeland’s 2022 budget speech, a rousing presentation that claimed the Canadian economy had sailed through the economic crisis. “Canada has come roaring back,” she said. The economy “is booming” and has “largely recovered.”

Today, five years after the 2020 COVID lockdowns, the great recovery from the excesses of the lockdown has yet to materialize in Canada, nor has much of the global economy returned to previous levels of economic achievement.

A recent commentary in The Economist illustrated the world’s failure to rebound from the pandemic. “In the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic — when hospitals overflowed, schools and offices shut, and economies seized up — many asked when the world would recover. Five years later, the data show that the setback to living standards could endure.”

Evidence that the world economy is a long way from recovery included a graph that plotted the global average Human Development Index. The HDI measures life expectancy at a national level, along with years of schooling and gross national income per person. The data followed a familiar path, with a sharp decline in 2020 and staggering recovery over the next few years, with projections of more decline through to 2030.

For most wealthy regions such as Canada, Europe and the United States, HDI scores remain high even after the pandemic, although Canada has fallen to 16th place down from 10th. Among poor nations, however, scores declined and show no sign of recovery. As The Economist put it, “for decades it looked as though on average the world would reach very high levels of development before 2030. If today’s sluggish progress continues, it could take decades longer to reach that milestone.”

Because of Canada’s advanced state of economic development, index measures such as life expectancy and education levels are unlikely to have changed through an event like the pandemic. However, more volatile and important economic indicators show Canada to be falling behind.

A few months ago, a Statistics Canada economic report plotted a graph that demonstrated the sharp impact of the pandemic on growth in GDP per capita. From its pre-pandemic trend peak of $58,100, real GDP per capita has fallen seven per cent, for a loss of $4,200 per person — equal to about $160 billion in lost GDP per year.

Story Continues

Can this loss be recovered? The report warns that it will not be easy. To get back to trend by 2030, the Canadian economy would have to generate annual real GDP growth of 1.7 per cent (as shown in the nearby graph), a rate well above Canada’s experience in recent decades when growth rates averaged 1.1 per cent or lower.

The latest numbers paint an even more difficult struggle for Canada. In 2023, GDP per capita fell 1.3 per cent, followed by another decline of 1.4 per cent in 2024 — at a time when the country needs 1.7 per cent growth to get back to trend by 2030. In the current economic environment, filled with trade wrangles, massive government deficits and a trend toward greater government involvement in directing the economy, the odds of recovery from the 2020 pandemic lockdown are even slimmer than they were a year or two ago.

To rebound from the pandemic, Canada’s economy needs major injections of market-driven capital investment and a regulatory environment that encourages competition, along with government fiscal and interventionist discipline, none of which are on the horizon.

• Email: tcorcoran@postmedia.com