At a pavement table outside Little Dom’s, an unfussy Italian a couple of miles down the hill from the Hollywood sign, Mark Hamill sits in a leather jacket despite the California sunshine and explains what it was like when he first saw the Beatles on television at the age of 12. For the whole summer of 1963 a girl on his street had From Me to You glued to her record player, so he was already familiar with their sound, but on February 9, 1964, the Fab Four appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. “The next day at school, there was nobody who hadn’t seen it,” he says. “Forget the space movies, it was — still is — the biggest revolution in showbusiness.”

Forget the space movies? For people of a certain age — my age — those space movies were as momentous as the Beatles had been for young Hamill. In the late Seventies and early Eighties we all had Star Wars-themed birthday parties and we all sunk our pocket money into Star Wars figurines. Playground conversation would turn invariably to Ewoks, lightsabers, stormtroopers and speeder bikes, and we all thought Jabba the Hutt was very lucky to have Princess Leia on a chain in her space bikini. Some of us got so absorbed in our Yoda impressions, talk normally we forgot how to.

Playing Luke Skywalker with his Jedi master, Yoda, in The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

ALAMY

To meet the man who was — is — Luke Skywalker, then, is quite the nostalgia trip. Unlike his co-star Harrison Ford, Hamill did not sustain a career as a Hollywood superstar. Although his film and television credits run to the several hundred, he has spent the post-Star Wars decades in the relative obscurity of bit parts, cameos, Broadway shows and voice work. When he tried to audition for the title role in the film adaptation of Amadeus, having played the part successfully on stage, its director, Milos Forman, told him bluntly: “Oh no no, the Luke Skywalker is not to be being the Mozart.” Tom Hulce was to be being Mozart instead. Like an ageing rock star still forced to play the hits from his debut album, Hamill remains trapped in a pop cultural moment of almost half a century ago. For a while in the 1990s he tried to downplay Star Wars in his Broadway credits — after a long list of theatre credits, his biography concluded with, “He’s also known for a series of popular space movies.” It took Carrie Fisher, lifelong friend and burster of bubbles, to put him straight — “Get over yourself,” he recently revealed she had told him. “You’re Luke Skywalker. I’m Princess Leia. Embrace it.”

Today, embracing it might be too strong, even if he did reprise the Skywalker role (and, spoiler alert, get to kill it off in the 2017 sequel The Last Jedi). “It wasn’t me that was the big star, it was the vehicle that is,” he says first before changing tack. “Harrison is a wonderful actor. When I tested with him and we didn’t have the whole [Star Wars] script, I just figured he was the leading man and I was the annoying sidekick. People would say, ‘Oh, you know Harrison got nominated for an Oscar for …’ whatever it was. I told them, ‘He deserves it.’ In other words, I can’t do what he does and nor would I try.”

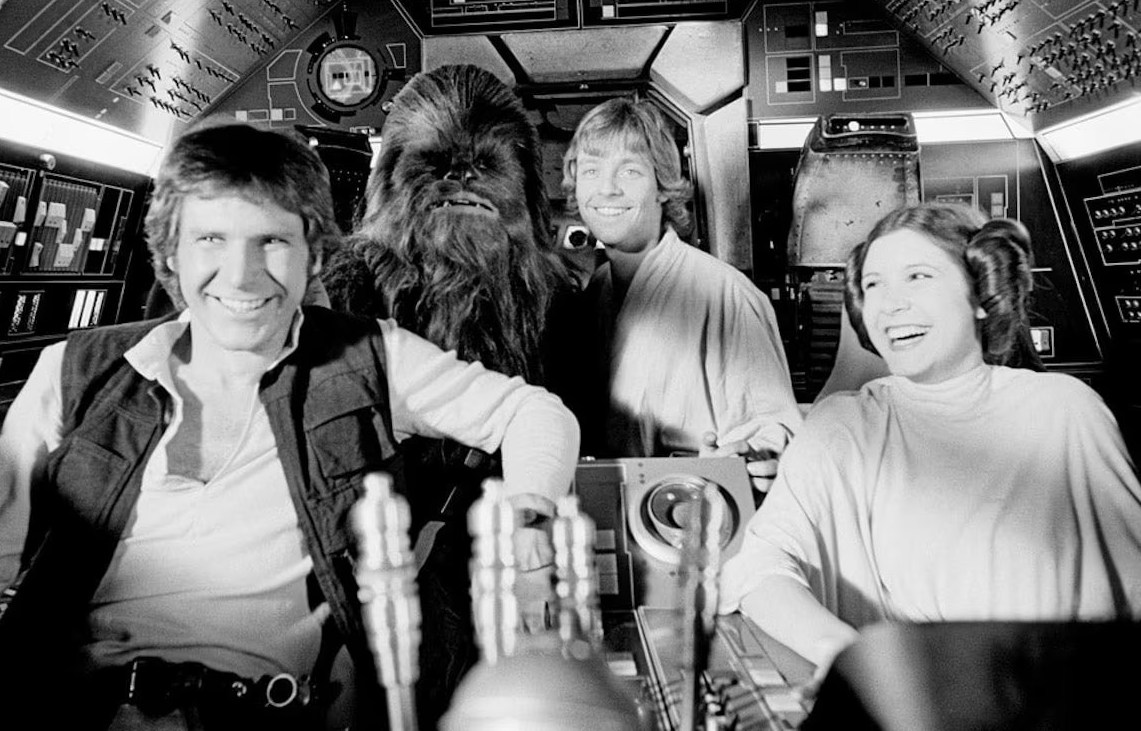

Filming Star Wars with Harrison Ford as Han Solo, Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca and Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia

LFL

Instead, Hamill claims, he is satisfied with life as “a working stiff … As a kid I’d see these character actors on The Twilight Zone and The Dick Van Dyke Show and I filed that away. ‘I love that guy. He’s always good. He shows up all the time in all these different things. What’s his name?’ It’s me!”

• The best Star Wars films and TV shows ranked — and the worst

This self-effacement is well rehearsed — he’s told other interviewers and, one suspects, himself many times in the mirror that he is happy with his lot. So much so that the 73-year-old says he was on the verge of retiring recently, the drive to get up and go to work having deserted him.“I was OK financially and really content with my family life,” he says. “My three kids live nearby so they can visit. I love the dogs [he has three]. I love my wife [he has one, Marilou, whom he married in 1978]. I love sitting out in the backyard with one of the two or three books I usually have on the go.”

Some other things happened instead. This summer Hamill is starring in not one but two big Stephen King adaptations. In The Life of Chuck, a feelgood movie about the end of the world, he plays a grieving, alcoholic grandfather trying to convince his grandson Chuck that accountancy is better than dance. In The Long Walk, a very, very brutal dystopian horror in which 100 boys must keep walking on pain of a bullet to the head until only one is left, he plays the Major, a fascist leader in postdemocratic, postapocalyptic America. Both are proper character parts in proper movies. Mark Hamill is having a renaissance.

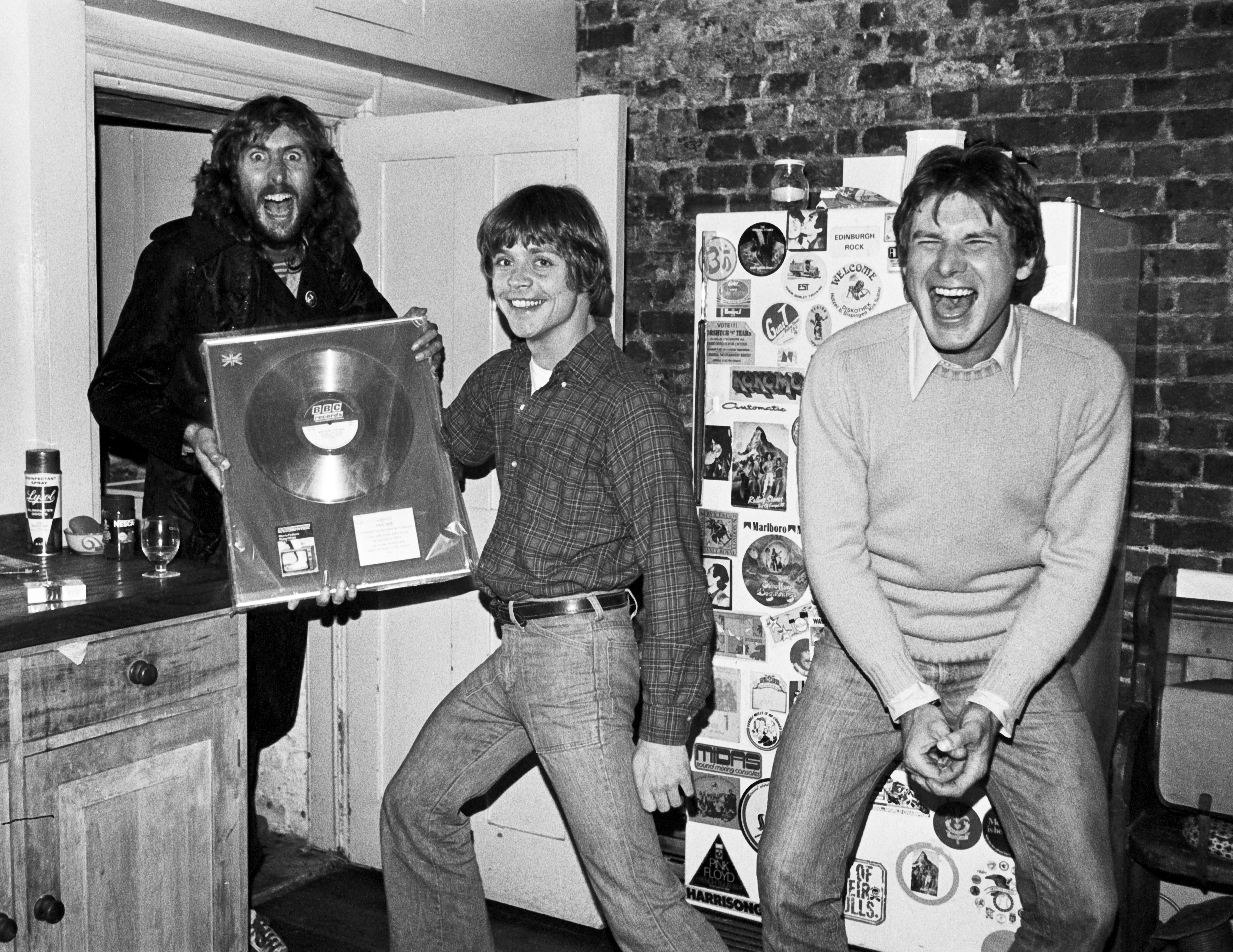

With Eric Idle, left, and Ford at Carrie Fisher’s rented flat in London, 1978. The gold record is by Monty Python

CAMERA PRESS

With his wife, Marilou, and their children, Nathan, Chelsea and Griffin, 2018

ALAMY

King wrote The Long Walk, his first novel, to impress a girl when he was a 19-year-old sophomore in the mid-Sixties as the US was embroiling itself in the Vietnam War. It’s hard now to imagine what it must have been like to live with the threat of conscription. Both King and Hamill were the perfect age for the draft — Hamill remembers it as “the most ghoulish game show ever where they drew birthdays — my birthday was only called at about 300 out of 365 but I had friends who got called within the first ten”.

At the height of the conflict Hamill was enrolled as a theatre student at Los Angeles City College. If he had dropped out to take acting jobs he would have been at risk — students could be exempted from the draft, waiters trying to get auditions could not. “And I would have been hopeless [in Vietnam],” he says. “I didn’t understand the war or why we were in the war. The idea of taking a gun and shooting another person — not for me. I would have had to have fled to Canada. I didn’t have the money to get to Australia or England.”

Such is his dislike of US gun culture, Hamill was reluctant to take the role of the Major — firing space lasers is one thing, executing boys for entertainment is another. “Francis Lawrence, the director, understood what was troubling me,” he says. “American society is gun violence and it’s hard to get past that, but as I spoke to him I realised this is just the guy. He said he would have been surprised if I wasn’t troubled by it.”

What was written as an allegory for Vietnam now becomes an allegory for modern America, something that Hamill, a lifelong and ardent Democrat, has long despaired of. “A few weeks ago ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] agents were pulling people out of their cars,” he says, pointing down the hill to LA, which has become a frontline city in President Trump’s clampdown on undocumented immigrants. “They wore masks and had no identification to show they were law enforcement. They were just brutalising people, kneeling on their necks. When I made the movie I wasn’t thinking in terms of it being timely but it’s proven to be just that.”

In a pivotal scene in The Life of Chuck Hamill’s character — old man, spectacles, white hair, whisky, about as far from cherubic Skywalker as you can imagine — gives a speech on the realities of life culminating in his belief that “the world loves dancers but it needs accountants”. Father figures — good ones and bad ones — are key to understanding Hamill and perhaps how a “working stiff” played those iconic “I am your father” scenes in The Empire Strikes Back with such vulnerability.

Hamill’s own father, William, was a navy captain in the US military at the height of the Cold War. The family moved from port to port, Hamill attending nine schools in 12 years in America and Japan. Good versus evil was his daily bread at a time when the generational gap between parents and kids was growing. Add in a good dose of strict Catholicism and it’s hard to resist concluding that Star Wars, or at least the moral absolutism of it, was not entirely science fiction for Hamill.

His father, William, a US navy captain

MARK HAMILL/X

When his father was on shore leave, he and his two brothers and four sisters — “Bill, Terry, Jan, me, Jeanie, Kim and Patrick,” he rattles off — were subjected to routine inspections “to make sure our beds were tucked right and all that stuff”. When his father was away, his mother — who snuck a vote for Kennedy rather than Nixon in 1960 (“don’t tell your father”) — relaxed and so did the children. TV dinners were allowed and TV, for Hamill, was everything. While his siblings fell into line — his older brother became a doctor, “so he was the big success in the family” — Hamill escaped into a world of comic books, superheroes and King Kong.

The Hamill family c 1959. Back row: Jan, Bill, William, Virginia, Terry. Front row: Mark, Jeanie, Kim

His father, of course, disapproved. “One time,” Hamill recalls, “after I’d left the house, I put my ear up to the door and I actually heard the words, ‘Sue, where did we go wrong?’ ” He laughs as he tells me this so I ask why. “Because I knew I was right,” he says, without hesitation.

As with so many origin stories there was a teacher, Mr Burrill, who taught Hamill drama at Yokohama High School in Japan and told him that if he applied himself he could make it as an actor. In some senseshe already was making it. Hamill had to be chameleon-like. “I’ll give you a perfect example,” he says. “I had a pair of powder-blue Levi’s — very cool in San Diego — but I made the mistake of wearing them when we moved to Annandale, Virginia. ‘Hey, look at Surfer Joe here,’ ” he mimics the other schoolkids. “I never wore those pants again but the nickname stuck. I hated it but I didn’t show it.”

His boyish good looks and perpetual new-kid status made Hamill an easy target for the jocks and bullies, but he would act his way out of trouble. “I’d perform scenes from Batman,” he says and gives me a burst of vintage Adam West and Burt Ward. “The people who would ordinarily be beating you up — I’d make them laugh.”

AUSTIN HARGRAVE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

The traditional route for wannabe actors with no connections was to move to New York and try for theatre auditions. At the risk of finding himself drafted to a faraway jungle, Hamill couldn’t do that. Instead he moved to Los Angeles and got a part in a 99 cent theatre called the Zephyr. Somehow, through luck and determination, he had an agent within four months. Jobs followed — five or six guest spots, a main part on the critically acclaimed but quickly cancelled comedy Tobacco Road and a recurring role on the daytime soap General Hospital. “I’d only ever watched soaps to openly mock them but it was great for learning technique.”

Proud of his early foothold in the industry, he invited his father to visit him on the lot at 20th Century Fox. They watched the screening of a legal drama together and Hamill asked what his father thought. “He thought it was a quite remarkable depiction of young law students and that if I ever considered going to law school, he would match me dollar for dollar,” he tells me. “I thought I could level this guy right now by telling him I had been paid three times what he earned for my last sitcom but I thought better of it. I just nodded and promised to think about it.”

Captain Hamill must have come around after the success of Star Wars, I suggest hopefully. “He didn’t really get it,” he says. “He was excited when Bob Hope asked me to be on his Christmas special.”

An early TV role in the US sitcom The Partridge Family, as Jerry, the boyfriend of Laurie Partridge, played by Susan Dey, 1971

I wonder if Hamill’s perspective changed when he became a father himself. “I tried to be the father I wanted but in retrospect I might have gone too far the other way,” he admits. “Only one of my kids went to college. She received all these accolades but both the boys didn’t go to college and I think what I should have done was give them an incentive…”

At which point his daughter, Chelsea, 37, who has driven him to the restaurant, looks at her watch three tables along. She’s caught between two roles today — that of an entertainment marketeer determined to keep to the schedule and that of a daughter who’s heard all her dad’s stories before. Yes, fine, we are here to talk about Hamill’s new roles but it’s almost impossible to suppress my inner nine-year-old and I find myself asking yet another question about a galaxy far, far away. Hamill is momentarily grumpy — he’s said everything he’s ever going to say about that.

Minutes later he’s talking about it anyway — as an unknown 25-year-old cast by George Lucas, he remembers how few people thought this strange space opera would be a hit. The studio couldn’t even decide how to market it. Was it a film about a voyage beyond our imagination or was it a comedy about some rascals in space? It premiered without proper posters.

“The first tip-off that it was something special was when I asked a driver to go by Grauman’s Chinese Theater because I wanted to see what it looked like up on the marquee,” he says. “It was the very first showing on the very first day but there were lines in both directions around the block. I’d assumed it would have a following of hardcore sci-fi fans, people like me, but I never expected it to be that big.”

Of the sudden and intense celebrity that came with it, Hamill reverts to his default ambivalence. “It was a lot,” he says, “but I knew that I hadn’t changed. Everybody else was going nuts but you try to reassure yourself that nothing’s really changed at all.”

As an alcoholic grandad in the Stephen King adaptation The Life of Chuck

ALAMY

Playing the evil Major in The Long Walk, another Stephen King adaptation

AVALON.RED

As a child he’d watched the Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night with a degree of envy. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be chased down the street by a pack of screaming girls,” he’d thought. “When I watched it again as an adult, it was a horror film! They couldn’t go anywhere. They had no life.”

Not that he didn’t try to enjoy his own fame. “At the height of it all I was in Vegas going out with the showgirls and enjoying the good life,” he says. “It was before STDs and it was, you know, recreational but it wasn’t me. Girls coming to the stage door asking me to come to their hotel — the sex will only take 15 minutes, they’d say, before listing all the other people they’d done.” He looks distressed at the memory but relaxes when I ask about his wife, Marilou.

“She was a dental hygienist and I went to get my teeth cleaned and I was just enamoured from the get-go,” he says. “I asked her out and I thought she better have a sense of humour. We went to see Annie Hall and she got it. She was an oasis in all the madness.”

• Star Wars top 50: the best moments, greatest characters, finest quotes and worst missteps

They married in December 1978 at the home they had just bought in Malibu. They had their first child, Nathan, in St John’s Wood, north London — they rented there while Hamill worked on the Star Wars films — but they have lived happily back in California almost ever since. In January the Palisades fire swept across the valley. The house survived but the whole area is still uninhabitable. Hamill doesn’t know how long it will be before they can return.

Hamill’s house narrowly avoided destruction in the LA wildfires in January

BACKGRID

In an industry powered by ego, it’s hard not to be suspicious of Hamill’s apparent lack of it but by the end of our conversation I’m sold. Typecast as a Jedi but still desperate to play character parts, he is at his most animated when talking about voiceover work (and its creative anonymity). His Joker in DC Comics’ Batman: The Animated Series is revered by fans just as much as his Skywalker. He is just as happy to do the Joker’s maniacal laugh on request in the grocery store as he is to show off his Jedi powers (he likes to wave his hand in time with motion sensors on electric doors). And despite talk of his retirement, he is clearly delighted with his chance to flex his full acting abilities in this Stephen King double-billing of a summer.

Today he fights not with a lightsaber but with a keyboard, using that wit honed through all those high schools. Having left Facebook because he was mad at Zuckerberg and Twitter because he was mad at Musk, he now expresses his horror at the state of America via Bluesky. I avoid mentioning Trump until the end of our conversation because it’s a subject that risks hijacking an entire afternoon. Sure enough, my late request for Hamill’s state of the union results in a lengthy monologue. “The bullying, the incompetence, the people in place… The only way I can deal with it without going crazy and wanting to open my veins in a warm tub is to look at it like a thick, sprawling political novel,” he says. “It’s entertaining in a way because this could actually be the end. Our status in the world has been crippled and that will reverberate for decades. Making Canada a 51st state? Do you know how offensive that is? And then taking over Greenland and renaming the Gulf of Mexico. The distractions are hilarious.”

With Harrison Ford at a concert in California, 2015

GETTY IMAGES

Hamill continues exasperating himself and then he tries to cheer himself up. “I still believe there are more honest, decent people than there are the Maga crowd,” he says. “If I didn’t, I’d move back to England.”

He could do an Ellen DeGeneres, I suggest, and try the Cotswolds. He nods and says that when Trump was re-elected, he gave his wife a choice: London or Ireland. “She’s very clever,” he says. “She didn’t respond right away but a week later she said, ‘I’m surprised you would allow him to force you out of your own country.’ That son of a bitch, I thought. I’m not leaving.”

I laugh and he laughs. Then I shake the hand that Darth Vader cut off and ask him to sign my Luke Skywalker figurine. It’s for my youngest, I lie, and he obliges. Hamill might be Skywalker and Skywalker might be Hamill but on the whole they both seem fine with it.

The Life of Chuck is in cinemas from Wednesday