An ambitious project that will help determine the safety of biking in California for the rest of the decade and beyond is now complete.

Caltrans, the state transportation department, has completed its two-year public outreach to Oakland and other municipalities about improvements it plans to make on and around state highways, including such major local thoroughfares as International Boulevard. (In the eyes of the state, International is Highway 185). The final updates to the overall bike plan were uploaded to the state’s website on August 5.

But while engagement on the general bike plan is over, outreach for “individual projects will continue forward as projects are programmed,” according to Caltrans public information officer Hector Chinchilla.

The majority of Caltrans roads are highways people can’t bike on. But the agency also maintains legal control over intersections above and under those structures, such as where Grand Avenue passes under the I-880. The state also controls areas around highway on- and off-ramps.

Last month, The Oaklandside detailed how the loss of state funding for construction on Grand Avenue reduced the scope of a project to implement safety improvements in front of Grand Lake Theater.

In a meeting of the city’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Commission last month, Caltrans staffer Jasmine Stitt presented the agency’s latest analysis of the state’s bike networks and the agency’s near-term priorities. She said one of the state’s goals is to make sure more people know about this plan than the last one, which came out in 2018.

”We at Caltrans actually don’t engage as much as we should have, and we’re trying to fix some of that,” she said.

The plan is designed to connect bike transportation networks that many California communities are already developing. That’s why state transit engineers, as part of their analysis, reviewed Oakland’s bike plan and plans created by other cities, some of which are in the process of being updated. Oakland is a designated part of the state’s District 4, which includes the nine-county Bay Area.

“ We wanted to look at what we’ve done well for the past six years, maybe what we could be doing better, improve what we can do to build on our success and make more comfortable, low-stress bike facilities,” Stitt said at the July 18 meeting.

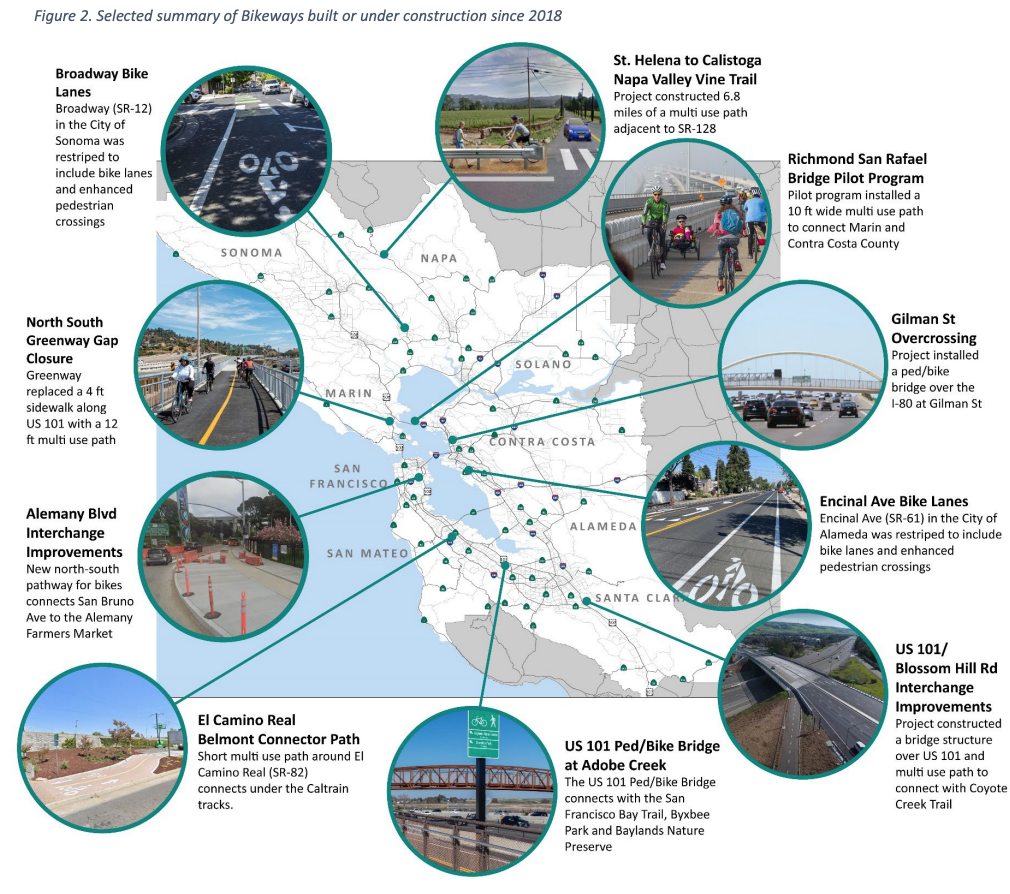

The last state cycling plan, issued in 2018, produced significant projects across the Bay Area. Credit: Caltrans

The last state cycling plan, issued in 2018, produced significant projects across the Bay Area. Credit: Caltrans

Caltrans is already working with the Oakland Department of Transportation on the East Bay Greenway, which runs alongside San Leandro Street and will eventually connect from San Leandro to downtown Oakland. Stitt said that through big projects like these — which could make a big difference in safety through a cycle track (a dedicated, multiple-lane track for cyclists), lighting, and a road diet (the reduction of a traffic lane to slow down cars) —Caltrans has learned it needs to streamline the permitting process to expedite completion.

Safe streets advocates in Oakland, such as Traffic Violence Rapid Response, have consistently raised the point that each time a road design project is postponed because of permitting, funding, or other administrative issues, deadly accidents continue apace. On trafficked roads like International and San Leandro, where people are killed and maimed every year, they insist that maintaining dangerous conditions is tantamount to negligence.

Stitt noted at the BPAC meeting that the state has often delegated maintenance of the right of way for bike paths to local jurisdictions that don’t have the capacity to perform this task, which has sometimes led to worsening conditions.

“The contents and maintenance agreements aren’t well known to even local jurisdictions,” she said.

As part of the plan, Caltrans engineers identified locations that need the most infrastructure help based on “safety, mobility, and equity.” Using Oakland’s Bike Plan and its High Injury Network map, the state determined that some major thoroughfares, including San Pablo Avenue and International Boulevard, need significant corridor improvements, as do the I-880 and I-24 ramps.

“For safety, we used crash density,” she said. “In Oakland, it’s high on safety, high on equity, high on mobility. International Boulevard is high on all three of these metrics.”

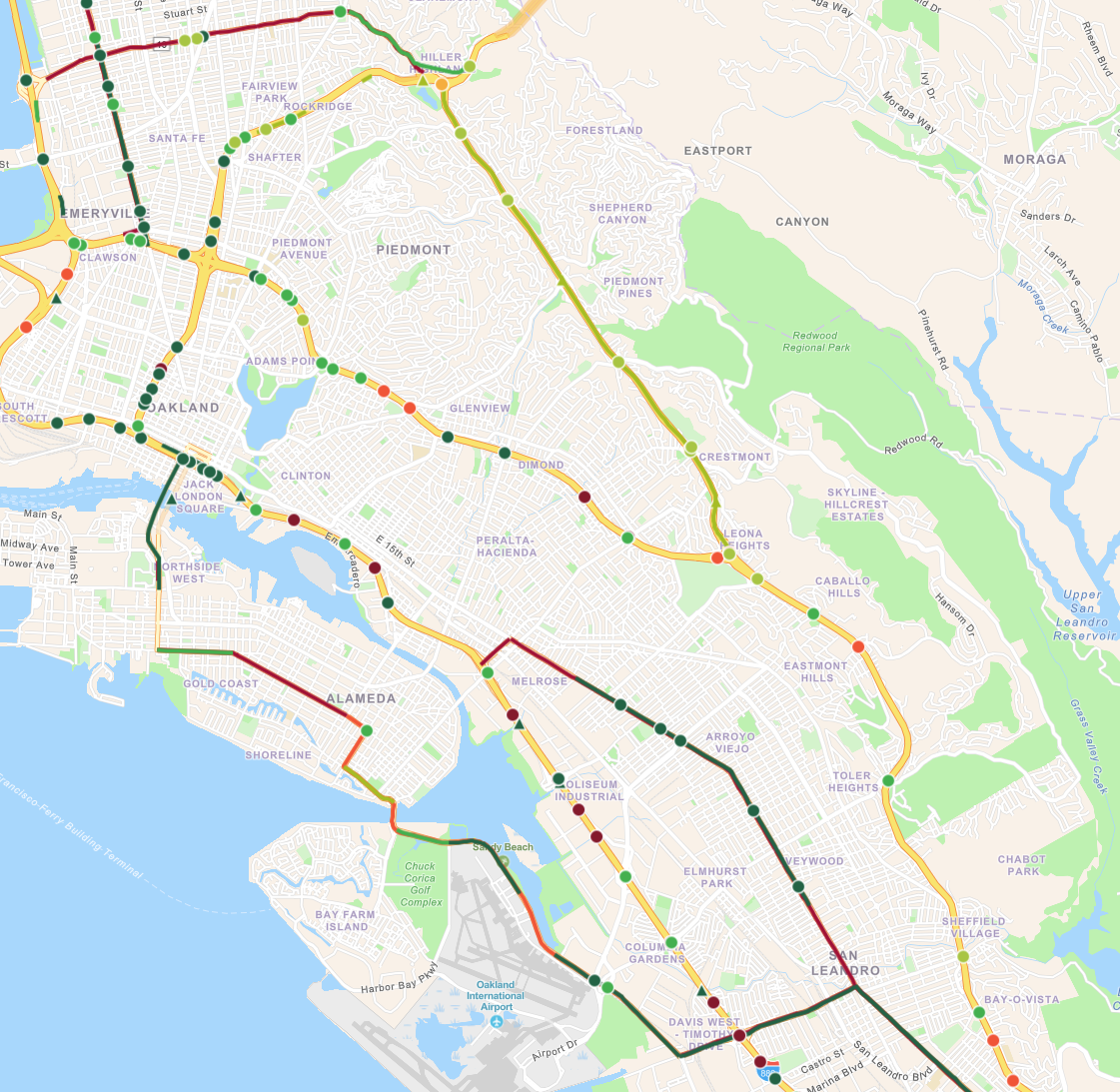

The map from Caltrans’ new pedestrian and bicycle plan for the Oakland area, finalized on August 5, includes improvements to intersections, ramps, and highway segments, demarcated by the highlighted roads and dots. Credit: Caltrans

The map from Caltrans’ new pedestrian and bicycle plan for the Oakland area, finalized on August 5, includes improvements to intersections, ramps, and highway segments, demarcated by the highlighted roads and dots. Credit: Caltrans

Improvements to other state-controlled Oakland roads have been highlighted as priorities in the plan, according to Caltrans’ updated needs map, which offers residents a way to better understand which locations may be improved in the future. They include protected bike lanes at several locations, including where Lake Park Avenue crosses over the I-580, where Broadway passes under I-580, and the 14th Street overpass above the I-980. They also include the creation of a separated bike lane parallel to Highway 13 and the removal of the slip lane at the northbound exit from the highway onto Joaquin Miller Road.

In all, Caltrans has identified 86 Oakland locations where the agency has jurisdiction that need improvements.

After a round of feedback from local transit agencies, the state has also updated its Bicycle Best Practices document.

One new recommendation is to design more “diamond”-type highway interchanges, where on and off ramps intersect with local roads at 90 degrees instead of through slip lanes, where drivers often fail to make a stop. An intersection at 90 degrees forces drivers to slow down and makes it easier for them to see a pedestrian or cyclist entering a crosswalk. Diamond interchanges, in the new Caltrans recommendation plans, appear with Class I or Class IV bike lanes on nearby roads.

Stitt invited the BPAC commissioners and locals to review the agency’s project analysis online.

According to Caltrans public officer Chinchilla, the official public comment period closed in June 2025 after two years of community workshops and an online survey that received over 1,500 responses. Chichilla said people can provide feedback on individual projects, such as the Doolittle Drive Preventive Maintenance Project, to improve bike mobility. Questions or feedback can be sent to Caltrans staff at d4bikeplan@dot.ca.gov.

“*” indicates required fields