It is a story of persecution and migration, the conflicting impulses of religion, politics and humanity. Above all, it is a tragedy in which identities are made and unmade, brutally and violently, over and over again.

Keeru bears the scars of a history that is all too familiar to anyone living in India or Pakistan, though it never allows history to become a scaffolding. Rafique’s brilliance shines through the characters she creates, as well as the deft control with which she reveals and holds back information about their lives.

The novel opens in the town of Surrey, near Vancouver, in Canada, but detours into Pakistan, where Keeru spent his early years. Told from five different perspectives, the action moves nimbly, braiding the past with the present so seamlessly that all time appears to be subsumed into the novel’s tragi-comic consciousness.

Keeru is a musalli, the equivalent of a Dalit, born to a poor couple in Pakistan. His mother is Christian and father Muslim, doomed as a couple from the start. Haleema Alice Bibi makes a living as a domestic worker. Her husband, Muhammad Hussain, who routinely assaulted and abused her, is dead. Their son Keeru is a bright boy, but ridiculed by his peers for his name, which means “a lowly insect, a bug, a pest.”

It seems only natural that Keeru should remind the reader of the most famous “vermin” in all of literature—Franz Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, in the story The Metamorphosis, who wakes up one morning to find himself literally transformed into a giant wriggling insect. But Keeru’s name has more metaphorical dignity and his metamorphosis is radically different from Gregor’s.

“I wanted to give my son a name that was all his own,” as Haleema tells the reader. “Every name I knew was related to a religion, a belief.” Having survived the horrors of Partition and the Shia-Sunni riots, followed by a spate of atrocities against religious minorities, she could scarcely be blamed for wanting to free her son of all divine baggage. But, more importantly, for Haleema, insects are not to be scoffed at. She finds them remarkably resilient, ancient creatures, which are able to overcome almost any adversity and find their way around the world.

₹499

₹499

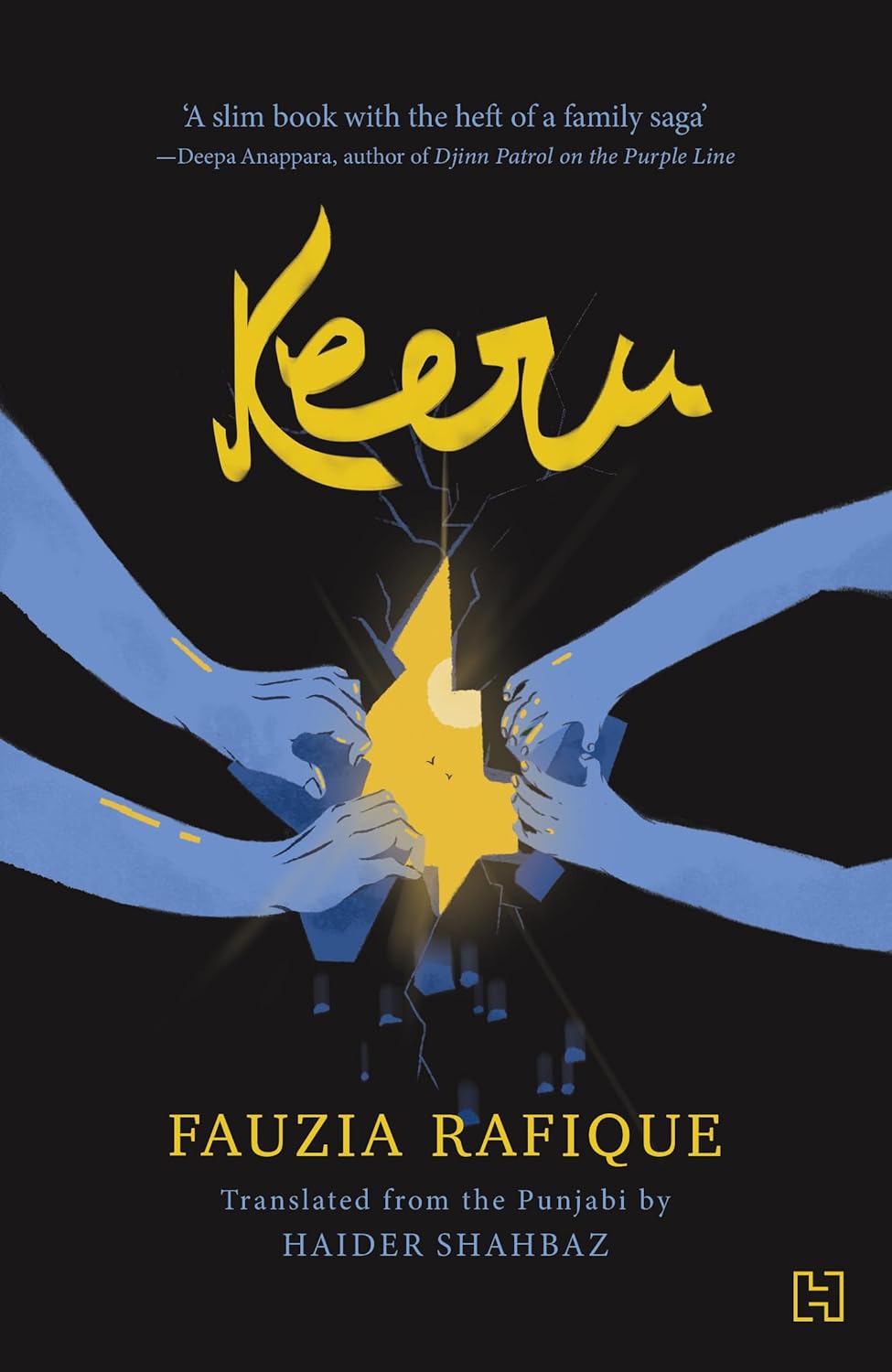

” title=”By Fauzia Rafique, Translated by Haider Shahbaz.

Hachette India, 168 pages, ₹499

“>

View Full Image

By Fauzia Rafique, Translated by Haider Shahbaz.

Hachette India, 168 pages, ₹499

As though to prove her right, Keeru lives up to the name his mother lovingly bestows on him. As a teenager, he gets falsely embroiled in a case of blasphemy, which is as good as a death sentence in Pakistan. It doesn’t take much to start a fire. Even something as trivial as a Christian boy drinking water during Ramzan sets off his Muslim classmates against him. As the local goons bay for Keeru’s blood, he is grievously injured, left for dead, but manages to live, like an insect impossible to destroy, and escapes the country.

He makes his way to Canada as a refugee, starts from scratch, overcomes all the hardships of immigrant life, does odd jobs, scrounges and saves, until he buys his own home and a garment business to boot. After years of living in exile, he manages to bring his beloved mother over.

For Haleema, her arrival in Canada becomes one of the many rebirths she has had in her tumultuous life: converting from Sikhism to Christianity to Islam, pushed around by predatory men, bloody politics and petty squabbles. Hers is the story of every immigrant who arrives at the promised land of hope and peace, before the sheen begins to fade from her eyes and the old world with its familiar troubles begins to rear its head again.

The past, in the form of internalised and inherited traumas, persists in the other characters, too, who surround Keeru. Naila, his business manager, struggles against the oppressive hold of her disabled husband Raheem, Keeru’s mentor. Isabella, a troubled girl born to British and South Asian parents, finds an anchor in Haleema after her anarchic and rudderless life. And finally, there is Daljit, another aspiring immigrant like Keeru, who starts off as his business partner, before he becomes his life partner.

This romantic twist in the tale—a subplot Rafique never quite prepares the reader for—gives the novel a unique frisson. The final hurdle Keeru must overcome in a life that has always been a brutal obstacle course is that of his sexuality. Even after years of living away from the society he grew up in, without the spectre of religion hovering over his head, Keeru finds it hard to live as he is meant to.

The moment of acceptance, when it arrives, is unexpected yet deeply satisfying. It is a gift that comes from the human heart—and from Rafique’s refusal to abide by the conventions of doomed love that queer narratives have historically been encumbered with. Sceptics may find the conclusion too neat, even idyllic. But what good is a story if it doesn’t inspire the reader to hope for better endings?