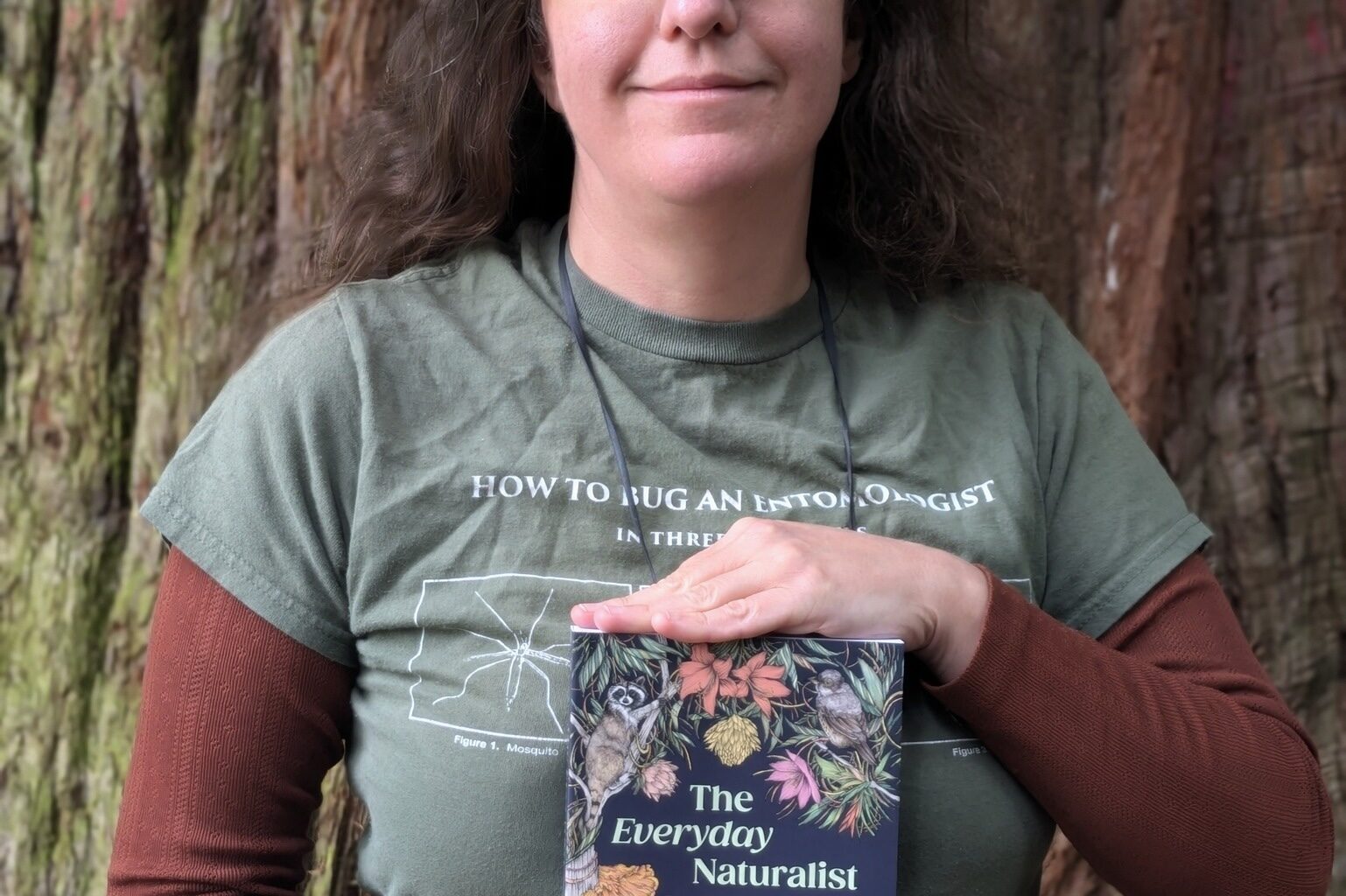

Editor’s note: Coast Weekend outdoors columnist Rebecca Lexa has published a book, “The Everyday Naturalist,” which was written while she was living on the Long Beach Peninsula. To accompany our book columnist Barbara Lloyd McMichael’s review, we asked Lexa to describe the joys and angst of the writing-publishing process.

“The Everyday Naturalist” is not only about the wildlife of the Columbia-Pacific — but it is very much a book informed by the nature I experienced in my eight years living there. It’s been a year since I had to move back to Portland for work, but every time I look at those pages I’m reminded of how this place shaped me as a writer.

Writers are a restless sort, words brimming just beneath the boundary of our skins, a wave that breaks and roils out over the page. No wonder so many of us escape to the outdoors to temper that restlessness. This book was called into being by the songs of coyotes, storm winds in Sitka spruce, the scent of cold brine and cloud-veiled sun.

These and more offered focus and encouragement in the months it took me to write the initial manuscript. I’d gotten my contract with Ten Speed Press in the summer of 2022, receiving the good news as I drove down U.S. Highway 101 in Oregon on my way to teach at the Sitka Center in Otis. I knew I wanted to be able to give the project as much undivided attention as possible, so I spent the next few months clearing the decks in preparation for my winter break.

The setting

I was fortunate enough to be living on my friends’ farm at the south end of Loomis Lake, tucked into a little “barndominium” by pasture and wetland, with a well-lit art studio in the upper floor. Across the road I could chat with the sheep and the llama and the chickens, and walk amid rows and rows of potted native plants awaiting their new homes. A large section of forest with old Sitka spruce near the lake became an easily accessible quiet oasis. It was the perfect place to be in this moment.

But no matter how perfect the setting, there’s still the challenge of pulling together enough words. I live by my outlines, always have. From their structure I’ve crafted articles, PowerPoints, curricula — and now an especially long one that was supposed to be the skeleton of a book. A few hundred seeds to produce 50,000 words, give or take, and you hope that the soil is fertile.

So after my daily farm chores and whatever other tasks needed immediate attention, I sat down at my computer each day. Sometimes I barely squeaked out two hours of work; on a few memorable occasions I managed to sequester myself for 12 or more hours, interrupted only by the insistent needs of my body. My single-day word-count record still stands at 6,777 words (not including those that fell before the backspace button), but there were many days where a tenth of that or less would have to suffice.

No block

You’re probably familiar with writer’s block, and my fellow wordsmiths likely have firsthand knowledge of it. I’ve never had an especially significant run-in with it, only finding myself unable to make the words flow on occasions when I am overall too fatigued or distracted to do much of anything but sleep, or escape to a friendly trail for a while (Black Lake got a lot of visits from me during my writing marathon). I once had the opportunity to ask one of my favorite authors, Peter S. Beagle, what his solution to writer’s block was. His response: “Remember that the bills are due next week.” We are of a similar drive, I think, though for me an impending deadline is also a primary motivator.

And there were times when I really had to push through exhaustion and the “I don’t wannas”. But I balanced that with remembering that rest is crucial to good work, and I took days off to allow my brain and body time to recover. I always rebounded with better words and higher word-counts, and what was contracted to be a 50,000 word manuscript came in at well over 70,000 — turned in weeks before deadline, even.

Tough

If you want to know the toughest part of the whole process, I have to say it was the editing. Not my editing, mind you. I’m fortunate enough to be what a friend calls a “third-draft writer”, where I can produce a pretty polished piece in the first go-round. My editor even said it was the cleanest manuscript she’d ever received in her long and tenured career, but that didn’t mean she didn’t work it over thoroughly. I didn’t have to “kill my darlings” as much as I had feared, but there were a lot of pointed questions and requests for clarification that made me seriously tighten up some of the material I’d taken for granted. The proofreaders and fact checkers also found some embarrassing oopses and errors that I’m glad never made it to the printed page. And my poor, beloved, lengthy bibliography ended up banished to a page on my website at https://rebeccalexa.com to keep the page count reasonable, with merely a link in the book’s introduction to mark its existence.

This decision allowed us to keep the bulk of the material intact, something that any book writer would appreciate. And that included anecdotes and studies of animals, plants and fungi that I encountered in my years on the peninsula. In fact, I had to consciously work to add variety to my examples, since this is supposed to be a book that can be used anywhere. I found myself constantly thinking of the beings in the conifer forests and the dunes, though, and many of them made it into these pages.

The two-year gestation was worth it, though, and I can confidently say that I have a book I am proud of having written. Was it really me who wrote it, though? I remember the process and the effort, but sequestered in a little apartment in northeast Portland, the barking of dogs outside the window is a pale imitation of coyote songs. A singular moment in my life has come and gone, as have many others. But at least this one left something lovely to remember it

• • •

About the illustrations

“You may have noticed the brilliant cover and interior illustrations by Colombian artist Ricardo Macía Lalinde. When the time came to choose the art for ‘The Everyday Naturalist,’ the art department at Penguin Random House (which owns Ten Speed Press) gathered sample works from more than a dozen talented artists, and arranged them in a PDF from most realistic to most stylized. Then they asked me to rank my favorites.

“Ricardo’s was the clear stand-out, even among such incredible works, and while PRH did the direct communication with him during the entire process, he was always very responsive to my feedback along the way. His amazing, eye-catching illustrations have made it incredibly easy to get people interested in the book, and I am honored to have our work featured together in this project.”

— Rebecca Lexa

• • •

“The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Animals, Plants, and Fungi Wherever You Go”

By Rebecca Lexa

Amazon.com, Time Enough Books, Ilwaco, $18.99