Too many young people are being signed off sick for struggling with hard work, the Government’s worklessness tsar has said.

Sir Charlie Mayfield said a mental health crisis among the young was being made worse by GPs writing sick notes for stress or anxiety caused by difficult tasks at work.

The former John Lewis boss, who is leading a government review into Britain’s growing worklessness crisis, said: “On the mental health issues among young people, the fact is your experiences at work are a very important contributor to that.

“Work can be tough. It’s meant to be tough. Sometimes you’re meant to find it hard. You’re not meant to ace everything or get everything right. And so there are times when it’s challenging.

“If you’re within a supportive environment and something that goes wrong, and you’re challenged … it can be a supportive and constructive process of improvement.

“If you’re in a situation where you don’t feel supported, you just feel criticised and you’re already feeling a bit vulnerable, it pushes you in the other direction. You may start to feel anxious, you may start to feel stressed.

“And of course, when you don’t have a system in place to support you, and you go to see your GP and you say, ‘I’m really anxious and I’m really stressed out at work,’ then what the GP may often say is, ‘Well, we better give you a fit note to sign you off work.’”

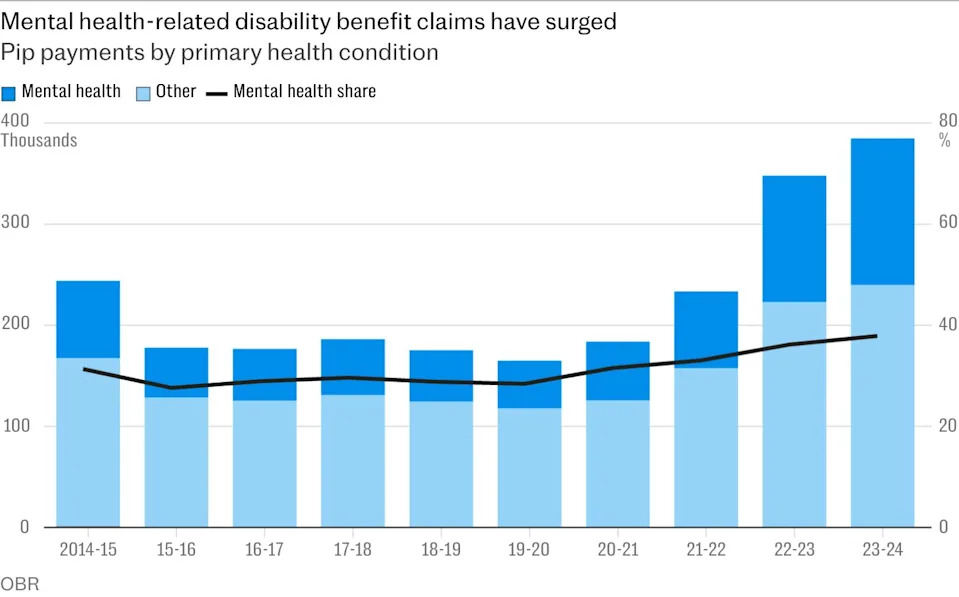

Climbing rates of anxiety and depression are a large factor behind the growing rates of economic inactivity in the UK, particularly among those aged under 35. Around a quarter of those who are economically inactive because of ill-health are younger than 35, and young people with mental health conditions are nearly five times more likely to be economically inactive than others in their age group.

Sir Charlie said mental health struggles should not be minimised but said problems were being “over-medicalised”. He argued that recommending people take time off for things like stress and anxiety risked making these problems worse, rather than treating them.

He said: “You go home, and you sit at home for a month, let’s say, with your anxiety or your stress, and then at the end of that month probably nothing’s happened other than the fact you haven’t been at work. But then the prospect of going back to work at that point may be even scarier than it was when you left it, because you’ve been away from it.

“The fact is workplaces are social environments. They’re communities, and it’s important to be a part of that community. A lot of mental health issues are made worse by not being engaged with some kind of community. You know, isolation is a bad thing for most mental health issues.”

Sir Charlie, who was chairman of John Lewis from 2007 to 2020, has been leading the government review into Britain’s growing worklessness crisis and is tasked with finding ways to keep ill and disabled people in the workforce. He is expected to report his policy recommendations in the autumn.

Soaring rates of illness and mental health problems since the pandemic have driven a sharp rise in the number of people falling out of the workforce.

There are now 2.8 million people classed as economically inactive because of long-term sickness, up from 2.1 million at the start of 2020, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Sir Charlie said businesses across the country were “heavily burdened”, with “a vanishingly small number” saying they had no issues with long-term sickness among their workforce.

The problem is placing a heavy burden on the public finances, too: Britain’s welfare bill is forecast to reach £70bn by the end of the decade as the number of people claiming disability and incapacity benefits rises.

“The scale of welfare benefits, and particularly the rate at which it’s increasing, is troubling,” Sir Charlie said. “I think any responsible government would be concerned about that.”

The Government has struggled to bring welfare spending down. Liz Kendall, the Work and Pensions Secretary, was forced to abandon several cost-saving changes to welfare policy this summer following a rebellion from Labour backbenchers.

Sir Charlie said the rise in worklessness since the pandemic had been fuelled by an increase in back and neck problems among older people and mental health problems among the young.

Many of his recommendations are expected to focus on how to address such health issues before they reach GPs.

“We have to really think seriously about how do we support people when they develop, or even before they develop, ill health issues at work … and if they do become acute, we can take steps to help people get back into work,” he said.

Sick note ‘force field’

Sir Charlie warned that fit notes, as sick notes are officially known, were too often leading people to drop out of the workforce.

While the fit note system is aimed at assessing a person’s ability to work, around 93pc declare that an employee should take time off.

Sir Charlie said businesses had told him fit notes were acting like “a force field”, creating a barrier between employers and their staff.

“What can often happen is that person becomes disengaged from the workplace very quickly, particularly when they have repeat fit notes … then an employer doesn’t really have any mechanisms to deal with that,” he said.

He added that employers told him they feared complaints, grievances or even industrial tribunals if they handled health issues incorrectly.

Sir Charlie said there was a “tremendous amount of fear in the workplace around health”, which was making it harder to both keep people in employment and get those suffering from conditions back into the workforce after time out.

On recruiting people with health conditions, he said: “Sometimes those people are fearful of disclosing conditions … because they find that if they do disclose things, they then don’t get jobs. Also, it’s fear from the employers who are saying if I have that person, is this going to lead to a problem down the track? I’d rather not take the risk.”

Sir Charlie said Britain could learn from Denmark and the Netherlands. Both nations emphasise the importance of participating in the labour force in any form, whether voluntary, part-time or full-time work.

“They make that point both from the economic benefits of it, but also the social and the integration benefits that come from working,” he said.

The former John Lewis boss said that a failure to address health at work would simply make the problem worse as more people seek medical treatment for issues that could be dealt with in other ways.

Sir Charlie said: “I think there’s an over-medicalisation of mental health issues, but it’s entirely predictable. If you go to see a medical practitioner, it’s highly likely that they will give you a medical diagnosis.

“Bringing more humanity back into the workplace is actually going to be a key part of what we need to do to address these issues.”