I don’t really feel fear, I’m slightly immune to it now,” says Jung Chang. The author of Wild Swans, the bestselling chronicle of her own, her grandmother’s and mother’s lives in 20th-century China, is referring specifically to the morning in 2006 when she entered her study to find the large plants that had adorned her balcony had vanished. Someone had meticulously untangled and cut them away from the trellis and removed them, while she and her husband, historian Jon Halliday, had been sleeping in the room just above.

“It was a warning shot from Beijing,” she says. “It reminded me of the scene in The Godfather in which the mafia sent a message by putting a horse’s head in a man’s bed while he slept. The intrusion was a coded message saying, ‘We can get you.’ But I’ve made up my mind: I’ll say what’s true and say exactly what I want to say.”

It’s impossible to understate the impact of Wild Swans, which was published in 1991 and became one of the bestselling non-fiction works of all time, selling more than 15 million copies and translated into 40 languages. Beginning with the unforgettable line, “At the age of 15 my grandmother became the concubine of a warlord general,” it documented Chang’s family’s harrowing experiences during Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution – when her father was tortured, paraded in the street and sent to a labour camp where he went insane.

Her mother was made to kneel on broken glass while a mob berated her, while the teenage Chang was banished from her home to be “reformed” by working as a peasant on the edge of the Himalayas.

The book attracted ecstatic reviews; everyone was talking about Chang’s insights into a country that had been virtually completely closed off to the rest of the world. Like many, I couldn’t put it down and I passed my battered copy to my daughters as soon as they were old enough.

For millions of admirers like me, it’s thrilling to learn that 34 years on, aged 73, Chang is finally publishing a sequel Fly, Wild Swans – reprising where Wild Swans ended. We left her leaving her hometown of Chengdu in southern China in 1978, as one of a group of 13 students allowed to study in London, dressed in identical baggy “Mao suits”, under strict instruction from the Chinese embassy, only to leave their hostel with permission and in pairs. “It was like landing on Mars,” she now recalls.

Today, sitting in a swanky restaurant near her home in Notting Hill, west London, Chang is friendly, fun and extremely chic in stripy trousers, a crisp crossover blouse, with perfect manicure and pedicure. Her lust for life is palpable: as a 26-year-old new to London, she seized every opportunity to enjoy her new environment. As a schoolgirl, she’d had to pull grass from the ground because Mao regarded lawns as bourgeois, so when she first visited Hyde Park, she was “overcome with joy”.

Gradually, she found the nerve to defy the embassy, join in college discos with other foreign students, wear make-up and colourful outfits found in jumble sales and visit pubs. She won a scholarship from York University, where in 1982 she gained a PhD in linguistics, the first woman from Communist China to be awarded a doctorate from a British university.

open image in gallery

Chang and her mother stand next to a portrait of her late father (Harper Collins)

As a child, she’d dreamed of becoming an author, but in Mao’s China, “writing was the most dangerous profession. Books were burned. I wrote my first poem on my 16th birthday and then flushed it down the toilet. But I was always writing in my head.” Starting afresh in the UK, she declined to write about – or even discuss China at first. “I wanted a new life, I didn’t want to think about the past.”

It was 1988, by which time – as she smilingly puts it – she was working as a lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies and “living in sin” with Halliday, now 86, when her mother visited her in London.

She didn’t share Chang’s passion for shopping in Oxford Street, so instead they went to Hyde Park. “She pointed at those round, flat stones on the ground and said, ‘That’s just the kind of stone they used to break the bones of baby girls’ feet.’ I began thinking about my grandmother’s bound feet and was absolutely flabbergasted, realising you had to break all four little toes, so they bent under the foot, but the nails continued growing, digging into the sole. I remembered how my grandmother would sigh with relief [when] soaking her feet, she’d say, ‘They say you get over the pain, but you never do.’”

Her mother began recording stories – 60 hours in total – which Chang listened to spellbound. She learned how her teenage grandmother ran away on those bound feet from her warlord master, so her baby daughter wouldn’t be brought up by his wife; how her mother was made to kneel in the snow for hours by the occupying Japanese military, who shot her schoolfriend dead in front of her.

open image in gallery

The best-selling book chronicling three generations of women has sold millions of copies (Harper Collins)

She was told of her grandmother’s gruelling 1000-mile walk across China during which she suffered a miscarriage, but her Communist official husband wouldn’t allow her to ride with him in his chauffeured Jeep, because it showed insufficient commitment to the revolution.

Chang turned these tales, and her own memories, into Wild Swans. After publication, she toured the world with her mother, who’d returned to China but had been allowed to leave, addressing rapturous audiences. Wild Swans has never been published in China, yet as the country briefly opened up and grew more prosperous under Jiang Zemin, black-market copies circulated relatively openly – something “unthinkable” in today’s increasingly repressive climate.

Mainly because the book was a family saga, rather than a direct criticism of the regime, Chang was then still allowed to visit China whenever she wished. Chang remembers a woman winding down her car window yelling, “I love your book”, another time finding her restaurant bill had been settled by another diner who was a fan.

Yet Chang couldn’t fully relish her success. The breast cancer she’d been diagnosed with and recovered from in 1990, which had been treated with surgery and radiotherapy, returned this time, necessitating a nine-hour mastectomy and breast reconstruction that took place just after publication.

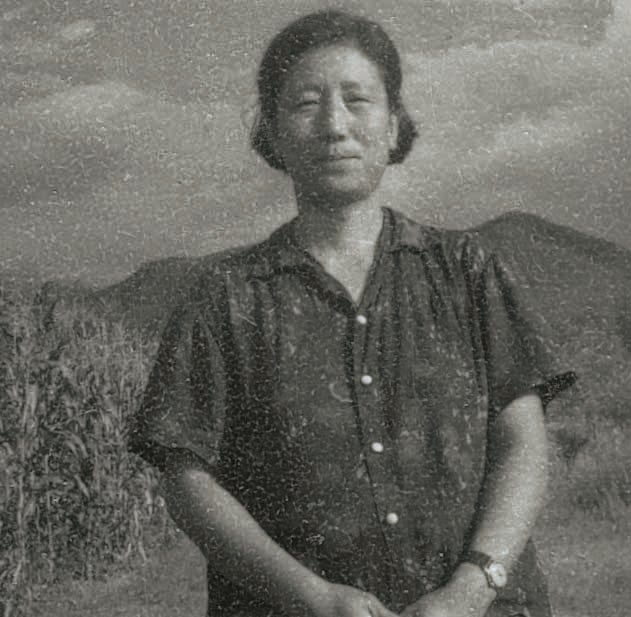

open image in gallery

‘She wanted me to write truthfully’: Jung Chang’s mother pictured in a labour camp (Harper Collins)

“The general anaesthetic left me permanently exhausted for years, so that took away some of the joy, as often I was just dying to collapse in bed. But of course I was very moved and excited by readers’ reactions.” Her illness meant she and Halliday couldn’t have a family – a source of regret, but to which she’s long since reconciled, “Our books are our children,” she says with a smile.

Chang and Halliday next collaborated on writing their biography Mao: The Unknown Story, spending 12 years interviewing 150 people all over the world, including Henry Kissinger, the Dalai Lama, George W Bush and Imelda Marcos. Their findings shook her. “I [became] conscious I was writing about true evil.”

They discovered that the leader, who died in 1976, had deliberately planned China’s Great Famine of 1958-61, by deciding to export food the population depended on to the Soviets to fund military expansion. In total, they calculated Mao was responsible for 70 million deaths during peacetime, yet to this day, some western historians continue to defend his legacy.

Yet in China, Mao still had godlike status, and Chang knew its rulers wouldn’t forgive her. Her visa application was revoked, so foreign secretary David Miliband had to negotiate her return for 15 days each year to see her mother. But after Xi Jinping took over in 2013, China became increasingly authoritarian. The last time she visited her adored mother was in 2018, just before Xi made himself permanent supreme leader.

open image in gallery

Chang and husband Jon Halliday ‘with Henry Kissinger (Harper Collins)

“One of the very first orders he gave after he came to this position was to make insulting revolutionary heroes a crime punishable by imprisonment. I’d documented Mao’s misrule, so I was ripe for the accusation.

“After years fighting to see my mother, I decided, agonisingly, I couldn’t try any more. I probably would still be let into China, but I might not be let out.”

Today, Chang dedicates Fly, Wild Swans to “My mother, whose deathbed I am unable to visit.” Now 94, she’s in a nursing home in Chengdu. Two of her brothers, one of whom lives in London and one in Canada, are also forbidden to re-enter China, having upset the regime in other ways, but her youngest brother and older sister still live nearby.

“Several times, my sister has been told to prepare for my mother’s death, but then she pulls through. Her mind is still there and until quite recently, I could have meaningful conversations with her, but in the past few weeks, she no longer has the energy to talk. “My brother brings her her favourite foods, when she sees him, her face breaks into a great smile.” Chang shows me a photo on her phone of the two beaming at each other. “I can’t tell you how much comfort that gives me.”

She continues, “It’s very sad I can never see her again, but that’s the professional hazard of being a writer and that’s what my mother encouraged me to do.

open image in gallery

Fly, Wild Swans picks up immediately from the first best-selling book (Harper Collins)

“She knew that’s where my heart and my gift lay. She wanted me to write truthfully and she knew from way back that there was a price to pay.”

The terror of the Mao years is still omnipresent. “Outside North Korea, the country that most determinedly asserts its communist nature is China. It has many capitalist features, but it’s a tightly controlled dictatorship that absolutely does not allow anyone to challenge it. Fear has come back in a big way amongst the population.”

Does she believe that it’s China, not Russia, that poses the West’s biggest threat? “Yes, in the sense that it asserts an ideology that’s specific goal is to destroy the capitalist world.” If Chang were living in Taiwan, would she be worried? “I would.”

Yet Chang will never be cowed. “We have to take some risks in order to enjoy our lives. I don’t write out of a desire to fight the Chinese government, but I’m in the unfortunate position where I want to write what I want to write and that’s subject to the tightest, nastiest control. But I can’t write about other things. So I can only carry on being as true to myself as I can be.”

And as she knows more than most, that comes with the biggest sacrifice.

Fly, Wild Swans: My Mother, Myself and China by Jung Chang (William Collins) is out 16 September