In 2025, photography has never been faster or more automated. Cameras track eyes at 60 frames per second and send 45-megapixel raws to your phone in seconds. Yet thousands of photographers are loading Kodak and Ilford rolls, proving film isn’t dead—it’s thriving as a cultural counterpunch.

The Emotional Pull of Analog

Film photography is slow in the best way. It forces you to breathe with the shot. Loading a roll into a vintage Nikon F or a Rolleiflex isn’t just mechanical; it’s ritual. The weight of the camera, the tension in the film advance, the click of the shutter—each step roots you in the moment in a way a mirrorless burst never can.

The first time I loaded a roll of Ilford HP5+ into my Canon AE-1 Program, I was a complete novice—still clinging to the Auto mode on my Canon Rebel T2i. Yes, the AE-1 has a Program setting, but I was looking for something more advanced than just another point-and-shoot experience. Using the AE-1 alongside my digital camera forced me to slow down in a way that was both unfamiliar and utterly captivating. Escaping the ease of digital automation, I began to experience each exposure with more purpose. Thirty-six frames suddenly felt like a gift and a challenge; every click demanded intention, and in return, it offered anticipation.

That’s the heart of the analog draw: intention. With only 36 frames, or 12 if you’re on 120, you shoot less but see more. You compose carefully. You notice the light shift across someone’s face because you’re not chimping the LCD. You’re present.

The Look That Digital Can’t Replicate

Yes, digital can approximate film. Fuji’s simulations are excellent. Dehancer and VSCO can create convincing halation and grain, but approximations are still simulations. Film’s depth is born from its physicality, light carving into emulsion, silver halides dancing in a chemical bath. Those imperfections aren’t defects; they’re fingerprints.

Each stock carries its own fingerprint. Kodak Portra 400 has a soft pastel roll-off. Ektar 100 punches with bold saturation. Ektachrome E100 slide film demands perfection (highly unforgiving) but rewards you with color that leaps off a light table. Black-and-white stocks like Tri-X and HP5+ carry a grit and soul that digital often struggles to mimic without heavy post-processing.

Medium format takes it further. A 6×6 negative from a Rolleiflex or Hasselblad has a depth and tonal separation that digital still chases. Grain, halation, edge softness, these “imperfections” are the look. They’re why entire industries work to emulate film inside digital cameras.

Hybrid Workflow: Film Meets Digital

Modern film photography isn’t anti-digital; it’s inherently hybrid. Today’s analog shooters live in both worlds, loading rolls in a 40-year-old Nikon, then processing the results through high-resolution digital workflows. The process has become a conversation between mediums rather than a competition.

Flatbed scanners like the Epson V600 and V850 or dedicated 35mm scanners like the Plustek 8200i have made high-quality home scanning affordable. DSLR and mirrorless “scanning” rigs using a macro lens to photograph negatives have pushed quality even further, especially for medium format. Once digitized, software like Negative Lab Pro turns Lightroom into a color-managed darkroom, allowing precise inversion and color balancing that rivals traditional optical printing.

A typical modern workflow can look like this: load Kodak Gold in a Canon AE-1, meter and shoot intentionally, then develop the roll at home with Cinestill CS41 in your kitchen. Dry the negatives, scan with a DSLR rig or flatbed, process the files in Lightroom or Capture One, and post the images online—all within a day. The tactile analog beginning and digital finish create a workflow that feels rooted yet current.

For professionals, this hybrid approach is essential. Clients rarely want contact sheets or physical prints as deliverables—they want digital files. Shooting film for mood, grain, and tonal depth, then scanning at high resolution, bridges that gap. Wedding photographers often shoot a few rolls of Portra or Tri-X alongside their digital coverage, using the film scans to add texture and nostalgia to a gallery. Commercial shooters incorporate medium format film for campaign hero images, scanning at drum-scan quality for massive print runs while keeping the rest of the job digital.

Hybrid workflows also open creative doors. Pushing and pulling film, cross-processing, or hand-coloring negatives can all be enhanced in the digital stage, letting photographers combine tactile analog experimentation with the precision of digital editing. For some, the scan itself becomes a canvas—dust, scratches, and edge rebates are left intact as part of the aesthetic. For others, the goal is a perfectly clean file that feels like it could have come straight from a modern sensor but with the unmistakable depth of film.

What this marriage of mediums ultimately proves is that film’s survival isn’t about rejecting technology—it’s about recontextualizing it. By combining the physicality of analog capture with the reach and flexibility of digital output, photographers are keeping film alive not as a relic, but as a vital part of modern visual culture.

Why Film Matters in 2025

Film Teaches Fundamentals: No histogram. No highlight alerts. You learn to meter light and pre-visualize exposure. Film forces you to understand the exposure triangle in a way digital can’t replicate. Mistakes cost money, and that sting makes you better.

Sustainability and Longevity: Film cameras outlast the digital upgrade cycle. My Canon 6D was outdated in five years. My Nikon F is from 1970 and still flawless with a $50 CLA every decade. Film keeps gear in use instead of being thrown in the landfills.

The Community Revival: Labs are reopening. Kodak re-released Gold in 120. Cinestill launched 400D. Boutique companies are hand-rolling emulsions. Online, film photographers swap recipes and repair tips daily. Analog isn’t just a medium; it’s a craft community.

Artistic Rebellion: In a world of instant everything, film is defiance. It refuses speed and demands patience. Waiting a week for a lab roll is photographic slow food, anti-algorithm art.

Voices from the Field: Working Photographers in 2025

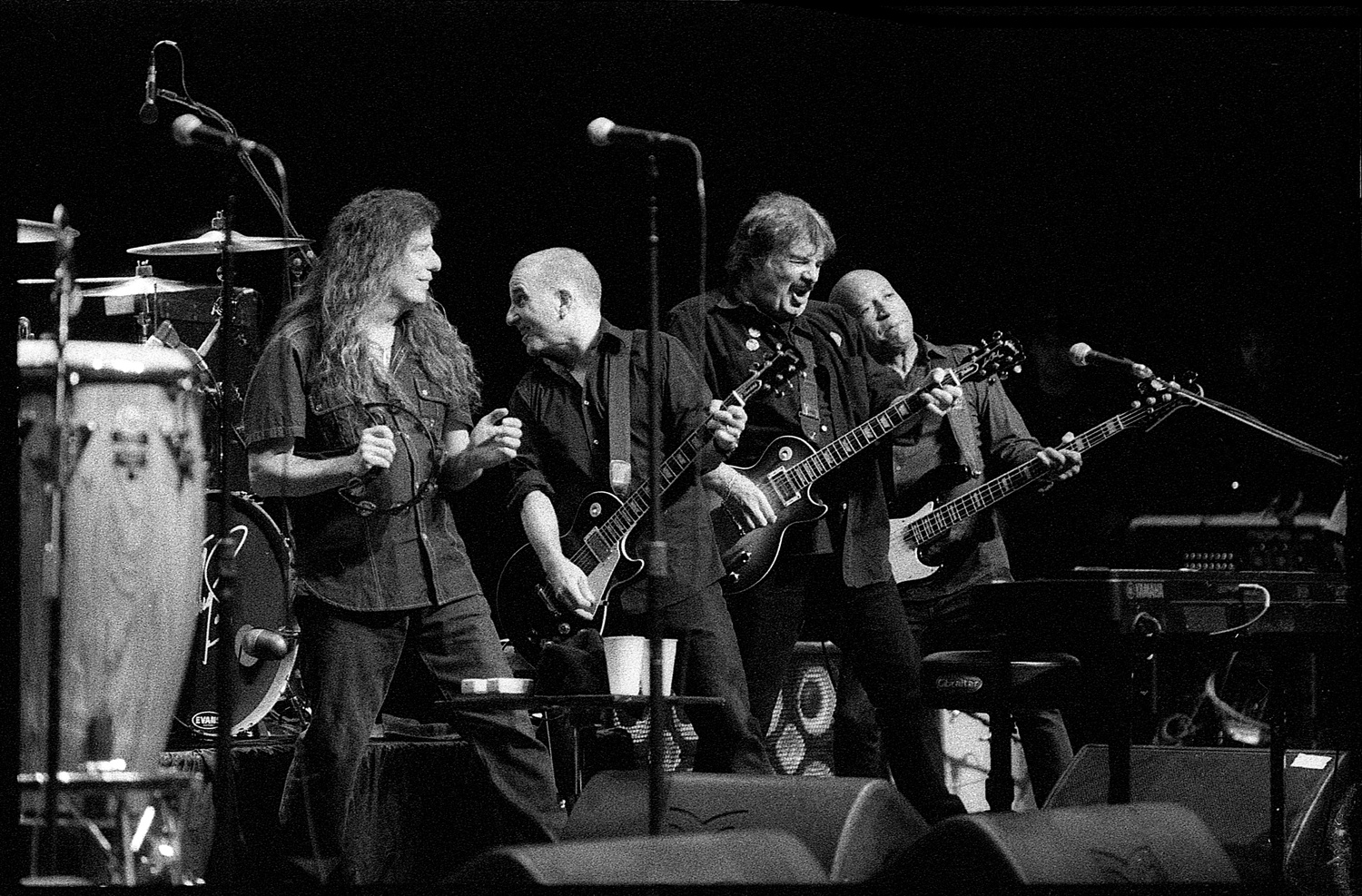

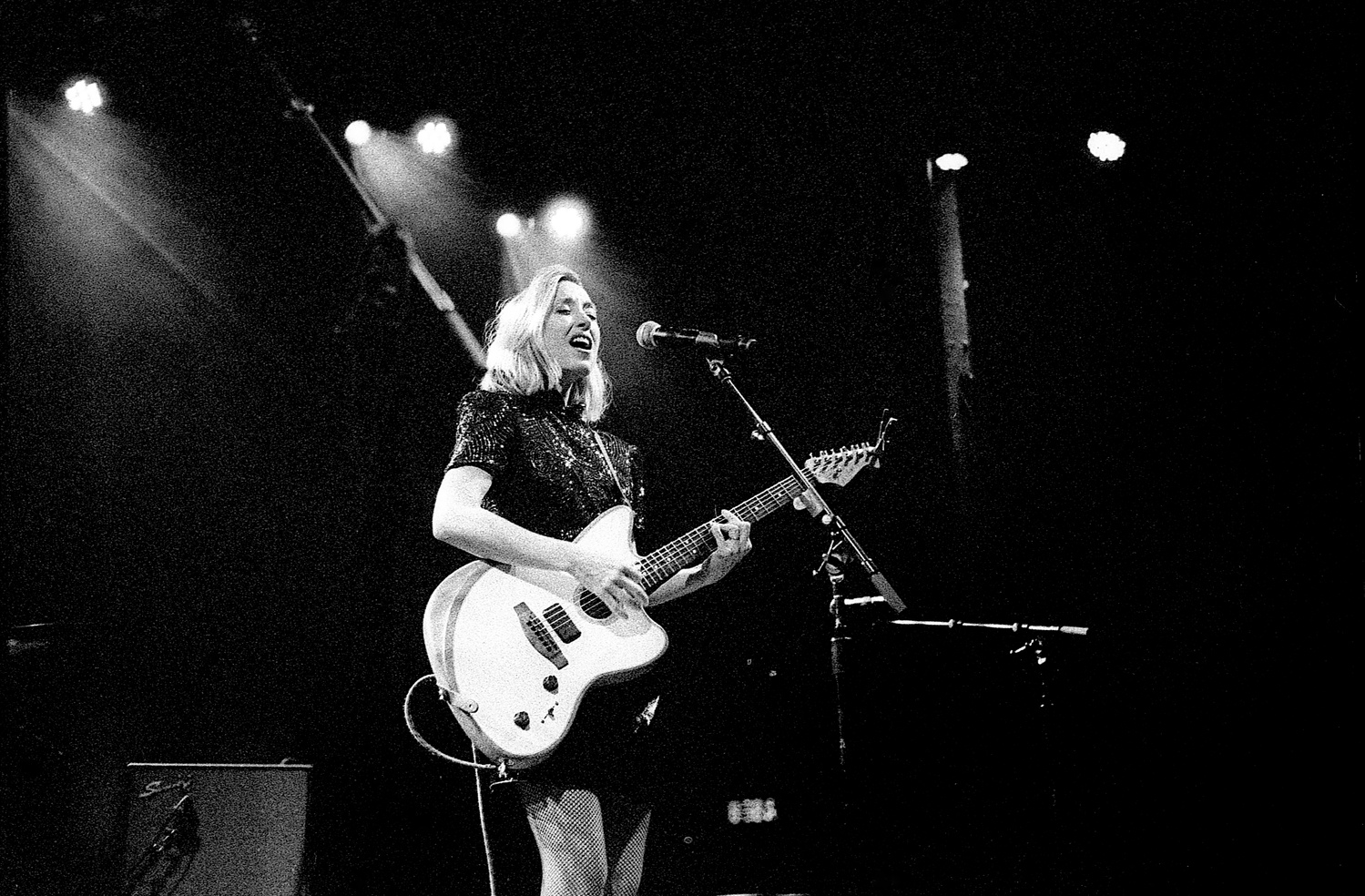

To see where film stands now, I spoke with two photographers keeping analog alive: Johnny Martyr, a veteran black-and-white shooter whose work is 100% film, and Kevin Camp, who balances digital with analog in his professional workflow.

For Johnny, choosing film was never about rejecting digital. “Honestly, I don’t even feel like I chose film over digital—it was more that I chose film as my starting point,” he told me. His first spark came in high school, watching his girlfriend shoot a Pentax K1000 and hand-print in the darkroom. “Seeing the care and thought that went into producing just one print opened my mind to how expressive you could be if you tried.”

Decades later, that spark still fuels his work. “At this point, it’s just become my thing. I’m always chasing the aspirations I had when I first started. Maybe I’m still shooting film because my mind is rooted in those early motivations. Shooting film keeps me grounded in what originally inspired me.”

Kevin’s pull toward film is rooted in creative limits. “Digital is a fine medium, but film offers the opportunity to do more creatively. When you load a roll of film you are shooting that ISO. You’re committed to that film choice with minimal changes allowed. So it’s a little more challenging, and I enjoy that. I also enjoy developing my own black-and-white, and that allows a certain amount of creativity as well.”

Johnny’s favorite stock? Kodak Tri-X for grit and history, and TMAX P3200 for its liberating speed. Kevin loves the challenge of large-format or providing Polaroids when clients request them, though he admits most non-photographers “think film doesn’t exist anymore.”

Both echo the hybrid workflow. Johnny develops in his kitchen sink. Kevin develops and scans black-and-white at home, outsourcing color development to a lab. Both stress that film teaches you to see differently. Kevin puts it this way: “It taught me to look for contrast instead of just pure exposure. Sometimes a technically ‘bad’ exposure—a blocked shadow or blown highlight—can carry more meaning than a perfect histogram.”

When it comes to lessons learned, Kevin credits film for teaching him flexibility in the process. “I know how my Nikon Z50 interprets shadows and highlights with each lens. I also know how my Mamiya C220f and Holga and Diana will see contrast and shadows. It taught me to look for contrast instead of just pure exposure. Sometimes, a technically “bad” exposure—a blocked shadow or blown highlight—can carry more meaning than a perfect histogram.”

Johnny frames it in terms of balancing craft and art. “My best work happens when the craft and art balance out and come together coherently. That’s always the goal.”

When I asked Kevin if clients ever request film specifically, his answer was telling. “Sometimes. I’ve had people ask for Polaroids or large format, but to be honest most non-photographers think film doesn’t exist anymore.” Johnny deals with a different version of the same problem: not convincing people film exists, but convincing them it’s worth hiring. “When you shoot all black-and-white, all grainy film, you have to prepare clients for what they’re getting. Commercially, it’s very different. That’s why I value my clients so much—they’re the ones who take the leap with me and see the value in it.”

As for where film photography is heading, both photographers agree: it’s not going to retake the industry, and it doesn’t have to. Kevin sees it as a “boutique medium, with only photographers who really want to shoot film still keeping what’s left of it alive.” Johnny is more optimistic about its cultural pull. “I think AI will push people back our way. As everything gets more sterile and perfectly in focus, people are going to rediscover the human hand in photography. Film and fully mechanical cameras—that’s the core soul of photography. I think people will keep coming back to that.”

Their advice for digital shooters considering film is simple. Kevin: “Don’t be afraid of it. It’s just a fixed ISO medium with a particular color palette and level of grain.” Johnny: “Shoot a lot. Don’t treat every roll like it’s precious. Build a relationship with your lab. And don’t obsess over buying more cameras—spend that money on film and time shooting instead.”

The Digital Pushback

Critics argue film’s resurgence is nostalgia-driven, and in some ways, they’re right. There’s nostalgia in every shutter click of a 50-year-old camera, every whir of a film advance lever worn smooth by decades of use. Loading a roll of Kodak in a Canon AE-1 does tug at a cultural memory, part family album, part art history. But nostalgia alone couldn’t sustain an industry that still requires chemistry, manufacturing, and distribution in a digital-first world. If it were just sentimentality, film would have faded out quietly like VHS.

Analog photography persists because it offers something digital simply can’t replicate: a tangible connection to light and time. When photons hit silver halide crystals, they don’t create ones and zeros. They leave a physical mark. A negative is not just a record of an image—it is the image. You can hold it up to the light, run your fingers over its edges, smell the faint trace of fixer on its surface. It’s an artifact.

That physicality changes the way we value images. Hard drives crash. Cloud subscriptions lapse. Social feeds churn through millions of photos in minutes. But a strip of film can sit in a shoebox for fifty years and still bring a moment back to life. There’s weight in that permanence, literally and metaphorically.

A friend of mine sent me some old slides of his parents from the late 1960s, one of which included himself as an infant. I scanned them on my Epson V600 and did very little editing. His reaction to having them digitized spoke volumes.

This is where film’s resurgence feels less like retro fetishism and more like a cultural correction. In an era where images are infinitely reproducible, instantly disposable, and often AI-generated, film reminds us that photography started as alchemy. It was light made material. That alchemy hasn’t been lost—it’s been waiting in the darkroom all along.

Film isn’t pushing back against digital to win; it’s pushing back to matter. To remind us that not every image needs to be frictionless, perfect, or immediate. Some should make you wait. Some should exist as objects. Some should demand care, both in their creation and in their keeping.

That pursuit of permanence is exactly what drives photographers like Johnny Martyr and Kevin Camp—loading rolls, developing by hand, and choosing a medium that turns moments into artifacts.

The Future of Film

The future of film isn’t mass adoption and it doesn’t need to be. Film doesn’t have to “beat” digital to justify its existence. Its survival hinges on a passionate niche keeping the craft alive, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing. Kodak, Ilford, and Cinestill are investing in new production runs. Boutique companies are hand-rolling emulsions. Startups are pushing innovation in unexpected places—Supersense, for example, revived peel-apart film with its One Instant project for Polaroid 100-series cameras, something most photographers thought was gone forever. In small workshops and garages, 3D-printed camera parts and even entirely new analog cameras are emerging, keeping aging gear in circulation and making new tools for an old medium.

Film education is also quietly fueling the next generation. College photography programs are dusting off their enlargers. High school students are learning exposure on Pentax K1000s. Community darkrooms are filling with people who weren’t alive when film was king yet feel drawn to its tactile pace in a digital world. This isn’t just preservation; it’s renewal.

The digital era hasn’t killed film—it has refined it. Because film is no longer the default, every roll becomes intentional. Loading a camera isn’t routine anymore—it’s a commitment. When you choose to shoot film in 2025, you’re making a quiet but powerful statement: this moment matters enough to slow down, to risk mistakes, to wait. In a culture obsessed with instant perfection, that choice carries weight.

And maybe that’s the real future of film, not as a mainstream format but as a counterbalance. A reminder that photography isn’t just about capturing pixels; it’s about capturing time. Whether it’s a strip of Tri-X drying over a kitchen sink or a box of forgotten negatives rediscovered decades later, film’s survival isn’t just about nostalgia or craft. It’s about ensuring that some images are made to last—not just for a feed, but for a lifetime.

Photographers like Johnny Martyr and Kevin Camp embody that connection every time they load a roll, proving that in 2025, film isn’t just surviving—it’s still speaking in a language only light and emulsion can translate.

Closing Thoughts

Film photography in 2025 isn’t about rejecting technology. It’s about choosing a different relationship with it. It’s about texture, imperfection, and the weight of twelve to thirty-six frames in your hand. It’s about the smell of fixer and the thrill of an image emerging on wet paper. In an era of endless, disposable images, analog still makes you care—and photographers like Johnny Martyr and Kevin Camp prove why that connection matters.

Images used with permission of Johnny Martyr and Kevin Camp.