FLUSHING MEADOWS, N.Y. — Has there ever been a more overindexed tennis match than Carlos Alcaraz’s U.S. Open defeat to Botic van de Zandschulp in 2024?

That shock loss, in straight sets in the second round, was held up at the time, and on many occasions since, as being indicative of Alcaraz’s inconsistency: as an example of his flakiness and his vulnerability against lesser players.

That might have a little weight away from the four most important tournaments in the sport but at the Grand Slams, it doesn’t stand up. That loss represents the only time in his last 12 majors that Alcaraz has failed to reach the quarterfinals, a record that stretches back to when he was 19. In that time, he has lost only to the four other leading players of the past few years: Jannik Sinner, Novak Djokovic, Daniil Medvedev and Alexander Zverev.

The latest of those 11 quarterfinals awaits at this year’s U.S. Open, where, for the first time in his career, Alcaraz has reached the last eight of a major without dropping a set. He has also reached the final of his previous seven events, two of them at Grand Slams. This is also the first year that he has reached the quarters of all four majors. And should Alcaraz match or better Sinner’s result in New York, he will be the world No. 1 next week. He is 34-1 in his last 35 matches.

At a news conference Sunday, Alcaraz seemed pleased to be asked about the lingering perceptions that he is a streaky player. Normally one to take a moment to gather his thoughts in a second language, the 22-year-old went straight in.

“Probably a lot of people have [said] that I am not as consistent as I should be,” he said after beating Arthur Rinderknech to set up Tuesday’s quarterfinal against Jiří Lehečka.

“But at the same time, those stats are really great to know for me, just to see that I’m making really good results in the really good tournaments.”

The persistence of the assumption that Alcaraz is inconsistent is down to a few factors. One is some relatively mixed results away from the majors. He this year lost to David Goffin (world No. 80) at the Miami Open and to Lehečka at the Qatar Open. Last year, Nicolás Jarry and Gaël Monfils were among those to take him down.

Another is Alcaraz’s ability to peak and trough within a match, even if he wins. The list of players to have taken a set off him at the majors over the last year or so includes Jesper de Jong (ranked No. 176 at the time), Li Tu (No. 186) and Damir Džumhur (No. 69). At this year’s Wimbledon, he was taken to five sets by Fabio Fognini, aged 38, ranked No. 138 and playing in his last event. But van de Zandschulp is the only major upset he’s ever suffered. Since first being seeded at a major, at the 2022 Australian Open, the lowest ranking to beat him is a world No. 10, and that was a guy named Sinner who ended up being alright.

As Alcaraz said last week: “Obviously I have my up and downs. I have matches that I don’t have or I don’t feel really good, but I just trying to survive those matches and to give myself another opportunity in the next round.”

The flaw in this perception of Alcaraz is mistaking volatility for inconsistency. To go with that list of dropped sets at majors, Alcaraz has a 14-1 record in five-set matches and a 5-1 record in Grand Slam finals. Since that first seeding in 2022, he is 341-81 at all levels, a win percentage of 81 percent; in 2025, he is 58-6, just under 91 percent.

Alcaraz’s gamestyle also feeds into this error of logic, partly because nearly everything he does is framed relative to Sinner. Positioning the two great rivals of men’s tennis as opposites is neither unnatural nor unreasonable, and since Sinner is characterised as the metronomic, mercilessly consistent one, it follows that Alcaraz should be the more mercurial, unpredictable one.

In some respects, that’s true, which is why Alcaraz has spent 36 weeks as world No. 1 compared to Sinner’s 64 and why the accurate consensus is that the Spaniard has the lower floor but higher ceiling.

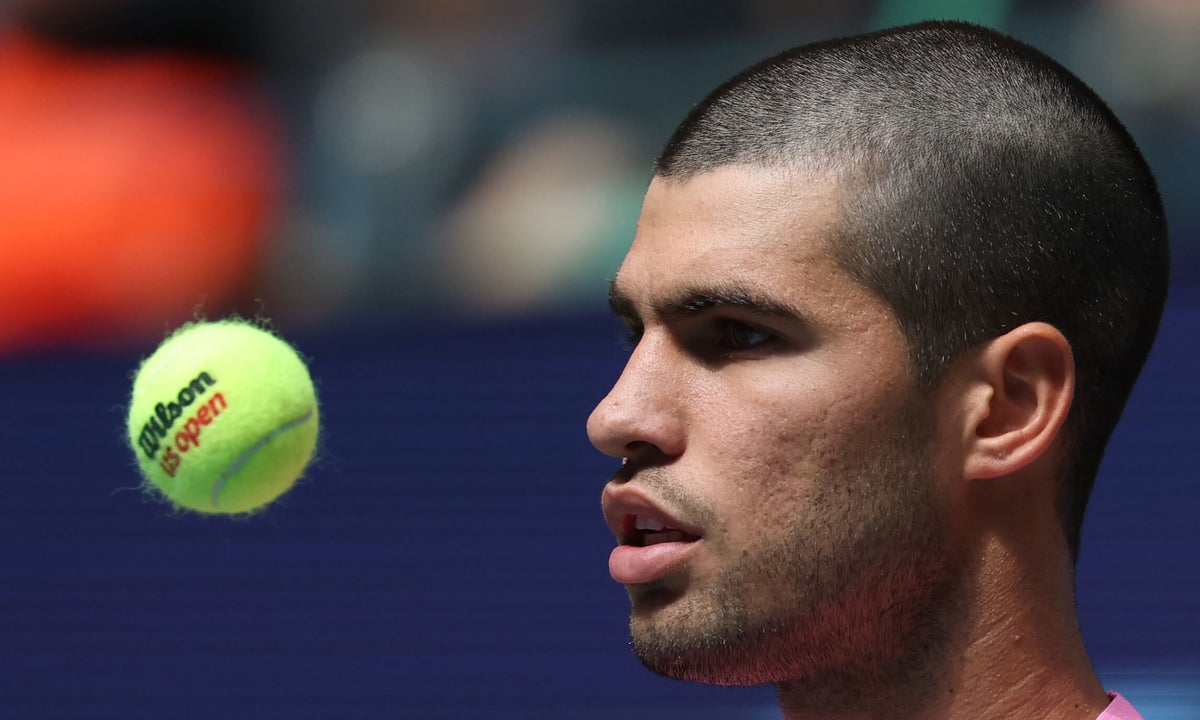

Carlos Alcaraz’s style of play makes him appear more inconsistent than he actually is. (Matthew Stockman / Getty Images)

But it also ignores the fact that both players push their opponents to their limit of their limits. Alcaraz does it with his unbelievable variety of attack and improvisational skill, forcing players to show off their end-range tennis. Sinner does it by asking them to show off their rally tolerance against some of the best, hardest and most consistent groundstrokes in the sport.

As a result, Alcaraz’s opponents get to showcase their own shotmaking and flair, which nearly every professional player has in their locker a few times a match. Rally tolerance with elite baseliners is a much more wearing skill, despite being the more consistently repeatable. Sinner’s way of winning is inherently less volatile than that of Alcaraz, but it doesn’t mean that Alcaraz wins any less, and he is equally capable of outhitting as he is defending.

The recent history of the sport on the men’s side also explains the short-circuiting effect of a player pairing such flair with relentless winning. Hotshot players — Monfils, Alexander Bublik, Pablo Cuevas — are too mercurial to win consistently and lack Alcaraz’s dual ability to stay grounded or go stratospheric.

Alcaraz is also developing into a more solid player. A big part of that is his improved serve, which has massively lifted his base level. Previously, Alcaraz’s dropped sets would stem from his relatively mediocre delivery being insufficient to protect the rest of his game when it went off the boil. That is no longer the case. Down break point in the second set against Rinderknech, he produced a service winner, then an ace to get himself out of trouble.

Small dips no longer have to mean dropped sets for Alcaraz, who has joked throughout the year about becoming a serve bot. In tennis speak, that means someone whose only weapon is their serve, which is clearly not the case with Alcaraz, but improving it has meant that some of his matches can feel a little less spectacular. His matches at the HSBC Championships in June, where the grass made his serve especially effective, were by his standards relatively humdrum.

At the U.S. Open, his matches have lacked jeopardy, but they have still featured some of his trademark shotmaking. Against Luciano Darderi in the third round, Alcaraz produced a ludicrous forehand return winner having received treatment for a niggle in his knee moments earlier. Against Rinderknech, he produced a majestic half-volley off a ball that was behind him, conjuring memories of a similar shot that he hit on the same court against Sinner three years ago. He then set up the decisive break in the third set with a mind-bending forehand passing shot on the run, having tracked down an overhead.

Against both Rinderknech and Reilly Opelka, the true serve bot who he met in the opening round, Alcaraz also timed his surges. He broke Opelka early in the first set of their match, but the next two breaks came at 5-5 and 4-4; against Rinderknech, he steamed away with a tiebreak after being down 2-1 in it, before breaking at 3-2 and 4-4. The two break points he saved against Rinderknech came right after breaking himself, avoiding the kind of volatile back-and-forth swing of not so long ago.

For Alcaraz, better scheduling has been key to his improvement.

“What I learned from this period, I took some days between swings or between tournaments which helped me a lot to come to another swing or to another tournament with a lot of energy, fresh mentally, just to perform at my best,” he said.

After being burned out toward the end of the past two seasons, and saying last September that the tennis schedule was “going to kill us in some way”, Alcaraz has taken matters into his own hands this year. He skipped the Madrid Open in May after deciding, unlike last year, that he wouldn’t risk going into the tournament carrying an injury, and then withdrew from the Canadian Open earlier this month to give himself a proper break after Wimbledon to relax and recharge at home.

Both of those tournaments are mandatory ATP Masters 1000 events, one rung below a Grand Slam. Missing them not only means forgoing the prize money and ranking points on offer, but also reducing a year-end bonus from the tour. Only the very top players can afford to make that kind of sacrifice. Sinner also missed the Canadian Open, while Djokovic has played a lighter schedule than most for years.

The result has been the unprecedented recent run of seven straight finals, with the opportunity to make it eight in a row this week. Which means that the Van de Zandschulp defeat is as significant as it’s made out, just not as a totem of Alcaraz’s inconsistency.

That loss came off the back of a particularly grueling schedule. Alcaraz was only a few weeks out from being shattered by an emotional defeat to Djokovic at the Paris Olympics. He also played the Cincinnati Open almost straight after the Games, looking a shadow of his usual self as he smashed a racket in an uncharacteristically anaemic defeat to Monfils.

By the time he played his first U.S. Open match, 23 days after the Olympic final, Alcaraz was still off. He struggled to a four-set win against the largely unknown Australian Tu, and the straight-sets loss to van de Zandschulp, who was ranked No. 74 at the time, arrived a few days later.

At this year’s U.S. Open, Alcaraz has vowed that history will not repeat itself. He focused on that straight after exorcising some of the Van de Zandschulp ghosts by thrashing Mattia Bellucci at the same stage of the tournament, for the loss of only four games. He added that upon returning to New York, he had thought more about the upset than his run to the title in 2022.

“The negative thoughts have more power than the positive thoughts,” he said after beating Bellucci 6-1, 6-0, 6-3. “I think that’s normal. I’m trying not to let them stick in my mind so many times or so much time on it, but sometimes it happens like this.

Carlos Alcaraz has flown through his matches at the U.S. Open. (Clive Brunskill / Getty Images)

“Looking back, I just wanted to improve from the experience that I have lived. I think when I lost in the second round, you know, last year, was one of those moments when I learned a lot how to deal with some situations, how should I have done things much better. I think I’ve just done it this year much, much better. So it was a great experience that I learned a lot from.”

A couple of days later, after another comprehensive win, this time over No. 32 seed Darderi to reach the fourth round, Alcaraz went back to the mantra: “I’m just trying not to do the same things as last year. Trying to improve and do the things much better. Every time that I step on the court, I’m just locked in since the first point until the last one. Yeah, I’m taking last year as motivation coming into this year, be more hungry, ambitious to do great things here.”

It appears that a more mature and balanced player and person is emerging as Alcaraz gets older. Aryna Sabalenka, another supposedly streaky player once upon a time, said after reaching her 11th straight Grand Slam quarterfinal on Sunday that: “I think that’s an incredible achievement. I think for me the key was balancing on and off-the-court life. I think I’ve done a great job on balancing really hard work and also great recovery and some fun time outside of the tennis court. I think that’s been the key.”

Likewise for Alcaraz, whose “French Open win followed by a trip to Ibiza” routine has become a sort of shorthand for how to nail work-life balance — even if members of his team were highly dubious the first time. Going on to win Wimbledon last year and to reach the final this year made for a pretty resounding rejoinder.

Ahead of Tuesday’s quarterfinal against Lehečka, Alcaraz said he’d found closure from the Van de Zandschulp loss: “Right now I’m not thinking about last year anymore.”

The rest of tennis should probably follow his lead.

(Top photo: Timothy A. Clary / AFP via Getty Images)