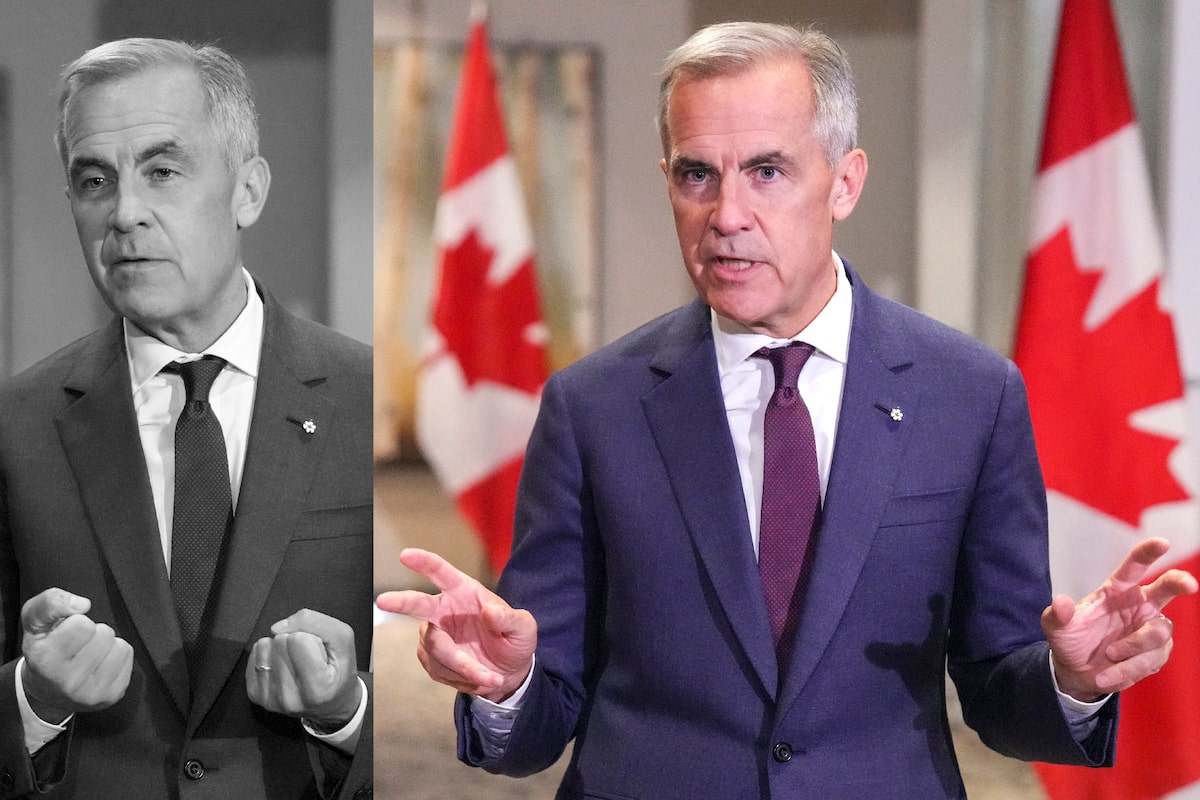

Asked if the fall budget would be an austerity budget, Prime Minister Mark Carney did not attempt to deny it, instead adapting it to a well-worn formula: ‘It’s an austerity and investment budget at the same time.’PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: THE GLOBE AND MAIL. SOURCE PHOTOS CHRIS YOUNG/The Canadian Press

It’s possible Mark Carney never meant to use the a-word. He was answering a question in French, after all, and you know how that can trip him up sometimes. But there it was.

Asked if the fall budget would be an austerity budget, the Prime Minister did not attempt to deny it. Neither did he answer another question, not asked, a favourite tactic of politicians. Rather, he adapted it to a well-worn formula: “It’s an austerity and investment budget at the same time.”

You remember: spend less, invest more. We heard a lot of that during the recent election campaign. How much less, or more, however, was left unsaid. It was before the announcements that Canada would make massive increases in defence spending, first to the existing NATO target of 2 per cent of GDP, eventually to either 3.5 or 5 per cent, depending on how you define it: an increase of $50-billion to $100-billion a year, minimum.

And it was before the letters went out from the Finance Minister to his cabinet colleagues, demanding they find ways to cut program spending by 7.5 per cent in the first year (the fiscal year starting next April), 10 per cent in the second, and 15 per cent in the third. That’s cumulative – spending is to be cut by a total of 15 per cent over three years – not additive, but it’s still a hefty sum.

Until then, you’ll recall, the line had been that any savings could be achieved through greater use of artificial intelligence. Public sector employment would be capped, not reduced. Nobody is talking like that any more. Indeed, the fiscal challenge facing the government is arguably greater than at any time in the last 30 years.

Five takeaways from Carney’s cabinet forum in Toronto

Start with the existing budget deficit, even before Mr. Carney’s “investments.” The deficit for the current fiscal year – the one the government has yet to produce a budget for, nearly six months after it started – is no longer projected at $39-billion, as it was in the last budget, nor is it $42-billion, as it was in the fall economic statement, nor is it even the $62-billion claimed in the Liberal platform this spring. A study by the C. D. Howe Institute, rather, puts it at $92-billion.

That, alas, was in July. The economy has shown marked signs of deteriorating since then, under the weight of Donald Trump’s on-again, off-again tariffs and the general chaos and uncertainty he has sown. GDP has been falling for the last three months. Investment is contracting sharply. Unemployment is rising. When the Chrétien government cut spending in the mid-1990s, Canada was rebounding out of a recession, pulled along by a surging U.S. expansion. This time around both countries appear to be sinking into a recession.

The long-term prospects are no less dismaying. Even before Mr. Trump’s re-election, it was clear that Canada had a growth crisis on its hands. The decades-long slide in real growth that had bedevilled policy-makers until lately has turned into an absolute decline, in per capita terms. Low and falling productivity is the reason. That’s troubling enough, from a competitive standpoint: Canada has watched while country after country has passed us by in the incomes standings. But it’s worse than that: if the country is to have any chance of paying the bills for a rapidly aging population, productivity needs to sharply increase.

The current exercise in program review, then, as ambitious as it sounds, would appear to be woefully inadequate. That 15-per-cent cumulative cut, you should understand, is not to program spending as a whole, now somewhere north of $500-billion, but only to certain portions of federal spending: operations, at roughly a quarter of the total, and the vast archipelago of discretionary transfers the federal government makes to organizations big and small across the country every year, worth another quarter of federal spending.

So we’re down to half of federal spending already. Allow for various other carve-outs deemed off-limits to cuts, and the C. D. Howe Institute calculates that program review will end up applying to just a third of federal spending, or $175-billion. That 15 per cent across the board cut – less, in certain sensitive departments – works out to just $22-billion by year three. That’s nowhere near enough. It’s not enough to rein in the deficit. It’s not enough even to prevent the debt from growing faster than the economy.

If we’re going to get ahead of our mounting debts – if we want to simultaneously find ways to get our economy growing faster – we are going to have to think much more radically. Specifically, we will have to dispense with some of the taboos that have unduly limited our options on fiscal policy for some time. To wit:

– You can’t cut transfers to individuals, or transfers to the provinces. Even now, with the walls closing in on him, the Prime Minister continues to maintain that there will be no cuts in transfers to individuals (Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, Employment Insurance, and the Canada Child Benefit) or to the province (the Canada Health Transfer, the Canada Social Transfer, and equalization).

This can no longer be plausibly maintained. It isn’t only the fiscal folly of walling off half of federal spending as untouchable. It’s that most of these transfers are ripe for reform. The Canada Child Benefit is an exception: a major policy success, it is the product of a previous round of reform, combining several different programs into one, income-tested benefit. Why could not the same thing be done with OAS/GIS? Does anyone think Employment Insurance, a program that has little to do with insurance and much to do with maintaining seasonal industries in perpetuity, represents rational public policy?

Everyone knows, likewise, that equalization has strayed far from its purpose – it is said not more than six people in the country understand the equalization formula – in a way that has become a massive irritant in federal-provincial affairs. Federal health and social transfers have also long outlived their usefulness: where once conditional transfers might have been needed as a catalyst for national standards, today they are among the main obstacles to health care reform.

Canadian exports rise in July, helping to narrow trade deficit

I grant that no federal government fancies tackling any of these if they can avoid it, but if a fiscal crisis isn’t the time to do it, when is?

– You can’t raise taxes. Or at least, you can’t raise the GST. At most times I’d be among those saying “we don’t have a revenue problem, we have a spending problem.” But the scale of the problem facing us – balancing a $90- or $100-billion deficit even as we are doubling or tripling defence spending – means that taboo also needs to be set aside.

But which taxes? Governments have already raised taxes at the top end about as far as they can be raised, realistically. There’s little additional revenue to be had. At a time when productivity is such a pressing concern, and when the United States is slashing its own income taxes, the usual arguments against raising income taxes – the disincentive to work, save and invest – seem if anything more pressing, not less.

That leaves the GST. Possibly the worst idea the Harper government ever had was to cut the tax by two percentage points, from 7 to 5 per cent. If the idea was to “starve the beast,” reining in spending by making less revenue available to spend, it failed: spending soared, not least under Mr. Harper. Governments simply raised other taxes.

Each percentage point on the GST now adds about $11-billion to federal revenues. Restoring the two points to the GST would make as much contribution to repairing our finances as the entire program review exercise, yet would leave it no higher than it was 20 years ago, and far lower than in most countries with similar taxes.

– You can’t cut the top rate of personal income tax. Most people understand that raising national productivity means raising our current anemic rates of investment. The best way to do that is to reduce barriers to investment: notably taxes.

Yet whenever the subject of tax reform comes up, somehow one idea is always ruled out from the start: cutting the tax that applies to most new investment, which is the top marginal income tax rate. You can’t cut taxes on the rich, it is explained. People won’t stand for it. Which is why the top rate of income tax remains higher now than it was in the 1980s.

I understand the sentiment. But it doesn’t make sense, even on its own terms. The tax rate that matters for economic efficiency is the marginal rate: the rate you pay on the next dollar you earn. But the rate that matters for distributional equity is the average rate: how much of your income you pay in tax, overall.

Simply cutting tax rates at the top, on its own, may not be politically saleable. But a wider exercise in tax reform, combining rate cuts with measures to broaden the tax base – eliminating inefficient preferences and deductions, especially those favoured by the well-to-do – might be.

It should be possible to design a reform that leaves those at the top paying more in tax, overall, even as it taxes their next dollar at a gentler rate, satisfying both equity and efficiency concerns at the same time. So: tax the rich on their stock options? Have at it. Tax capital gains at the same rate as ordinary income – including gains on the sale of their mansions? Fill your boots. Tighten up the dividend tax credit, crack down on the use of private corporations to shelter income: yes, and yes.

But don’t whack them at the moment they’re doing something useful: making a new investment. They can afford it, but we can’t.