Jenna Mahale interviews Philippa Snow about her new books “It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame” and “Snow Business.” :quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2FIt's%20terrible%20the%20things.jpg)

Snow Business by Philippa Snow. isolarii, 2025. 284 pages.

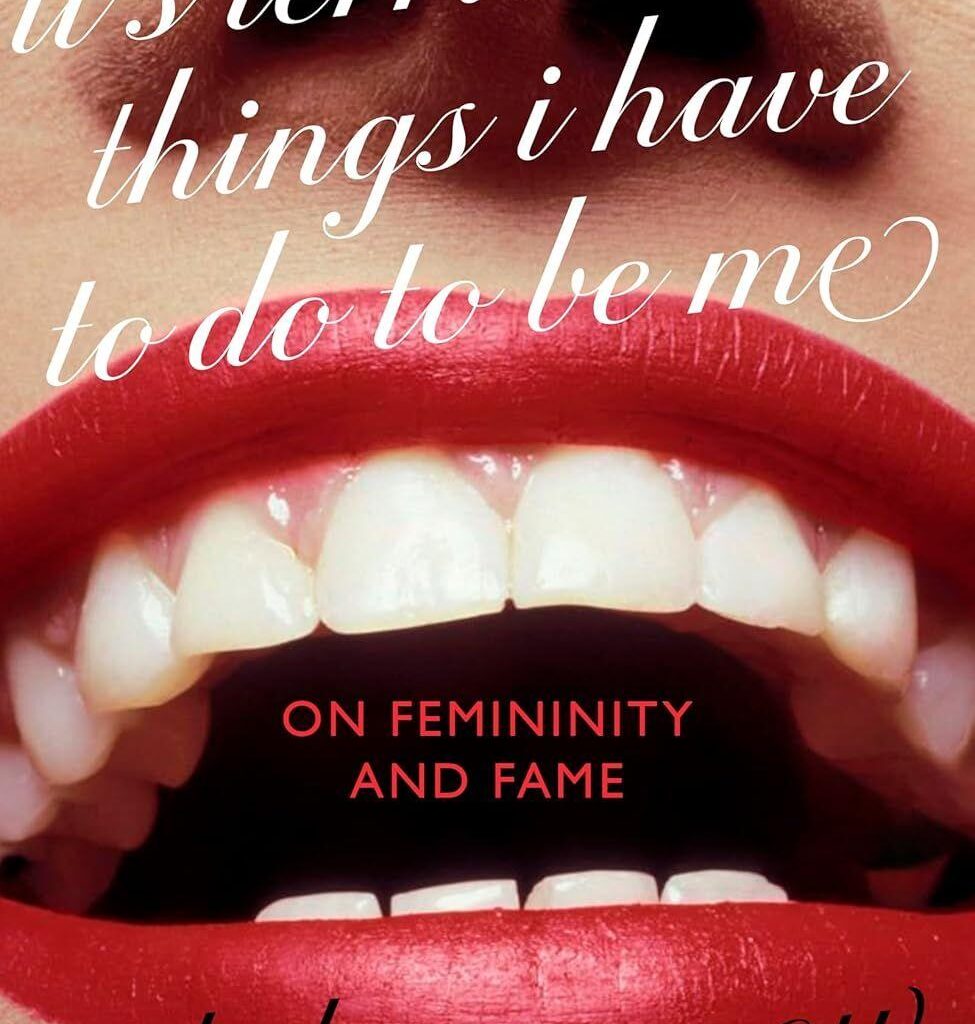

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame by Philippa Snow. Virago, 2025. 304 pages.

PHILIPPA SNOW’S fascination with the things people do to transform themselves “physically, psychologically, conceptually—in order to better adapt to fame”—has led her to write four impressive books in about as many years. The first, Which as You Know Means Violence (2022), was a 120-page examination of the use of injury (its terror, eroticism, and gendered politics in particular) by practitioners like Yoko Ono and Marina Abramović, as well as entertainment vehicles from the Jackass franchise to Logan Paul’s abominable YouTube channel. Snow’s extended essay Trophy Lives (2024) approached the celebrity as an art object, making sense of the cultural obsession with exclusionary beauty and self-generative mythology by choosing subjects like Maurizio Cattelan’s sculptures of Stephanie Seymour, Amalia Ulman’s irony-pilled online performances, and the Rizzoli coffee table book of Kim Kardashian selfies.

A critic and essayist by trade, the Norwichian author describes her third book (a pocket-sized tome tongue-in-cheekily titled Snow Business) as a “record of [her] ongoing interest in the influence of so-called girlboss feminism.” The book is a collection of previously published reviews, essays, and short fiction that Snow wrote between 2019 and 2025, primarily discussing the work of Western directors through subjects like sex, theology and Vanderpump Rules. Snow Business also looks into what the celebrity novel might unintentionally express about its authors, considering the abounding identity politics of Sex and the City, the opportunistic sleaze of James Franco, and more, before a final section comprising four short stories, each narrated from the perspective of a female celebrity—or one of their silver screen characters.

In July, Snow published her latest and most extensive work to date, whose title is a phrase once spoken in court by Anna Nicole Smith. It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: On Femininity and Fame consists of seven essays, each pairing two celebrities from different eras to better illustrate their artistic contributions, as well as exploring themes such as self-objectification as self-empowerment, or how desirability can make its possessor into a hate object. Snow darts back and forth between biographies to draw out the similarities between them: Smith and Marilyn Monroe, ambitious and ultimately doomed women who made careers out of performing “bottle-blonde burlesques of femininity”; the twin tragedies in the stories of Aaliyah and Britney Spears alongside their staggering industry ascents; how former child actors like Elizabeth Taylor and Lindsay Lohan embraced divadom in service of reinvention, leaning into a nihilistic hedonism usually only reserved for their male counterparts or, in the case of Amy Winehouse, electing to align one’s identity with the masculine in a society where femininity is necessarily performed, frequently punished, and commodified in perpetuity.

The book’s thesis hinges on an observation of Andrea Long Chu’s, that a female can be defined as somebody who has undergone a “psychic operation in which the self is sacrificed to make room for the desires of another.” Viewing the female celebrity as the ultimate metonym for womanhood, Snow proposes famous women as the “most female” of us all: a prism that also reflects some of the more mundane “alterations of the self” characteristic to feminine life. Drawing on an immense archive of reportage, she asks in each case how an icon becomes an icon—and what exactly does it cost?

¤

JENNA MAHALE: It’s Terrible earns an intimate familiarity with its subjects through a remarkable range of sources. How did you go about beginning these investigations?

PHILIPPA SNOW: Absolutely. So I think something that might be obvious from reading my essays, both in It’s Terrible and elsewhere, is that one thing I’m really excited by is tying a couple of unlikely details together—I’ll tend to seize on some minor touch in a story, especially one that either feels boldly symbolic or has some sort of gothic extremity to it, and then, once I have that small fact or anecdote, my goal will be to find a mirror for it elsewhere. In writing this book, because these are essays about women with literally mirrored lives or personas, that was a very explicit technique. I suppose my research, which is not technically all that organized as I don’t have an academic background, could be characterized as quite magpie-like for this reason. With these women, I would read multiple biographies where multiple biographies were available, but you’re looking for that seam of gold in them, or that little diamond glint, which allows you to imagine where a full essay is going to go. I’m thinking, for instance, about Anna Nicole Smith dying in Hollywood, Florida, as opposed to the “real” Hollywood like her idol Marilyn—it’s such a perfectly instructive detail, as I say in the book, that it almost feels invented, quasi-novelistic.

Which of your subjects were the trickiest to research?

Caroline “Tula” Cossey, the “trans Bond girl” and model, was perhaps the subject with the least available coverage—she wrote two memoirs, but neither is easy to find, and one I could not get hold of at all. By complete chance, it turned out that my local library in Norwich had a copy in their research-only section, because Cossey was a Norfolk girl, and it came under the heading of local history. But if you contrast someone like her with someone like Marilyn Monroe, of course there’s such a wealth of information available about the latter that it would take years to read it all.

Were there people or pairings you toyed with that didn’t make it in?

We cut two at the planning stage. One was Pam Grier and Sharon Stone, and the other was Sharon Tate and the actress and Playboy model Dorothy Stratten. Actually, I’m still very keen to write the second one, but the brilliant artist and poet Cristine Brache has already produced some wonderful material about Dorothy Stratten so perhaps my voice isn’t needed there.

I’m curious about your own background in art. What were you like as an artist, what was the kind of work you were interested in, and what did you ultimately take away from that experience?

As an artist, I would describe myself as “not very good”! Joking aside, though—and this is laughably obvious as a biographical detail now when you look at my writing—I was very into photographing female nudes, with this dramatic, S&M-inflected style that was very inspired by Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton. I think the biggest influence art school ended up having on my work was the time I spent in group critiques, because that made it obvious to me that what I really enjoyed was not producing work but figuring out what other people’s work was trying to say.

I read in an old bio of yours that a formative moment for you as a child was when you rode a parade float that ended up catching fire. Can you say more about that experience and how it shaped you?

Oh God, what a factoid to pull out! I included that there because I was asked for an offbeat bio, and a detail about my life that hadn’t been used before. I was being sort of flippant, but there is something about it that feels very me—this bathos, an intersection between being looked at and danger or destruction. I was dressed as a hippy at the time, as was every other child on the float, if that helps to fill out the mental image.

Key themes in your work include feminism, sex, celebrity, identity, and reality TV. You’ve also said you’re drawn to “extreme characters”—who’s caught your attention at present?

I’m gearing up to write a long essay about Bonnie Blue and the other extreme performers of OnlyFans, I think, though I’m not sure what form it will take yet. It feels as if it would be an interesting continuation of my writing about Jackass in my first book—she is, as viewed from one angle, kind of a sexual stuntwoman, and from another, a sort of erotic performance artist. I also think—and this is a thought that hasn’t yet fully been formed, so to some degree I am only partly owning it—that the hysteria around it is misplaced, in the sense that she’s said she was motivated to sleep with 1,000 men simply because the market demanded it, and the problem (or “problem”) is probably more that anyone feels the need to do anything extreme or dangerous with their bodies to make money, rather than the sex itself. God knows who will publish it, and what my thoughts will end up being once I’ve actually researched it, but there’s a half-baked and slightly edgy scoop for you, I suppose.

How do you think we might begin to try and compensate the “wildly underpaid” entertainers whom we use “for things that are worth more than money,” as one critic you quote wrote regarding Britney Spears?

I think as a culture, we’re trying to compensate them by acknowledging their selfhood at present, which was not really a form of compensation that Britney was granted. I would say that we should also grant them the space, if we’re talking about the wronged women of the past, to be imperfect victims. People were incredibly behind Britney when the discussion was about freeing her from the conservatorship, but I remember there being a lot of judgment, masked as concern, once she started expressing herself by doing things like appearing naked on her Instagram. I guess all that is just part and parcel of acknowledging stars’ selfhood too.

I’d like to talk about your flash fiction series Screen Shots, which explores the inner lives of various famous women and the humanity of characters they’ve portrayed. For me, these pieces also feel successful as creative nonfiction. What is it about a subject that leads you to this embodied mode of writing?

I’ve realized they’re all quite angry women, aren’t they? Angry and wronged women. Maybe I’m drawn to female characters who act out in ways that I don’t—that idea of extremity again, and of the feminine tipping over into the grotesque. I remember there was one week for the column I wrote a story from the perspective of Cher’s character in Moonstruck, because I wanted to do something nice for a change, and then it didn’t end up being one of the ones I chose. Actually, one of the ones that appears in Snow Business is the germ of a novel I’m hoping to start writing eventually.

One of my favorite essays from Snow Business is “Oh, I Remember Her!” (which was, of course, originally written for the Los Angeles Review of Books). In it you describe the Sex and the City reboot as a “psyop-like” dramedy with few highlights, and I can’t say I disagree. My question to you is, Are you still keeping up with And Just Like That?

For my sins, I am watching And Just Like That every week, and every week it makes me more baffled and furious. I’m not sure why I do it to myself—as much as I pass judgment on some aspects of the original Sex and the City, I still adore it, and I wonder if I’m watching now out of a sort of misplaced sense of duty to the original characters, as if bearing witness to their perpetual embarrassment will give them a kind of … dignity? God knows. Even the official HBO account has started posting about Aidan as if he’s a horror movie villain, so maybe we’ve all just entered some sort of collective psychosis.

Both of your latest books quote the legendary Andrea Long Chu: in Snow Business to consider the idea of all fiction as incidentally autofictional, and in It’s Terrible to define the condition of femaleness. Do you remember when and how you first came across her work?

It’s a very appropriate answer: by reading an essay she’d written about Sex and the City! I think she’s a great prose stylist and also hysterically funny, which is so rare. You should read this Sex and the City piece, which was published by Post45. I haven’t reread it in years but I’m confident it will hold up, and I remember it having several genuinely laugh-out-loud phrases in it.

In the context of the role of the fashion critic, Rachel Tashjian spoke recently about how establishing a sense of authority is a significant part of that profession’s ultimate goal. Authority is also the title of Long Chu’s most recent collection of criticism; when asked about her polemical writing, she traced its origins in Christian apologetics. Is there a guiding aim to your criticism?

I don’t know that I consider myself an authority on anything, per se. The fact that I bounce from art to film to popular culture and back means that I am a bit of a jack-of-all-trades, master of … writing about Lindsay Lohan, perhaps? I will say that for me, criticism is often about helping myself to understand how I feel about culture, and how I operate in the world, even if I’m doing that subconsciously. And then I think if it helps readers to understand something about themselves, that’s fantastic too. Or it might just help them to decide to skip a show, or a film! I’m pleased that it has any utility for other people. I’m just here trying to figure out what the fuck my deal is, I guess.

LARB Contributor

Jenna Mahale is a writer and editor based in London.

Share

Copy link to articleLARB Staff Recommendations

Ilana Masad interviews Emma Copley Eisenberg about her first novel, “Housemates.”

Helena Aeberli looks for rizz in Adam Aleksic’s “Algospeak: How Social Media Is Transforming the Future of Language.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!