Credit: Raymond Shubinski

The article recounts the author’s personal journey into astronomy, highlighting several influential beginner astronomy guidebooks from various eras, including “Stars: A Guide to the Constellations,” “Astronomy With an Opera-Glass,” and Patrick Moore’s “The Observer’s Book of Astronomy.”

The author reviews several key historical guidebooks, detailing their content, authors, and impact on their astronomical learning, noting the evolution of presentation styles from illustrated books to vinyl records and planispheres.

The article contrasts beginner guides, focusing on basic celestial navigation and constellation identification, with more advanced guides covering telescope usage, observational techniques, and specialized celestial objects.

The author emphasizes the enduring value of various astronomy guides, both print and non-print media, and their role in fostering a lifelong passion for astronomy, regardless of the reader’s level of expertise.

An interest in astronomy may strike early in life or later. Regardless of what lit the fire of that interest, you need knowledge to help you understand the universe. Some of the most important sources of information are the many beginner’s guides on astronomy. No matter what form these guides may take, they provide the basic information needed to send the enthusiast on an exciting lifelong journey.

Personal history

I can’t remember exactly when I became interested in astronomy, but I was young. My mother bought me my first astronomy guidebook when I was 8 years old. We were checking out at a dime store when I spotted a pocket-sized Golden Nature Guide called Stars: A Guide to the Constellations, Sun, Moon, Planets, and other Features of the Heavens. I’m embarrassed to say my mother finally took the book to the register and bought it for me to stop my begging. It was part of a pantheon of nature books published by the Golden Press, and it was developed and edited by Herbert S. Zim.

Astronomer Robert H. Baker wrote this little book, which was first published in 1951. Baker was already well-known for his previous publications, including Introducing the Constellations in 1937. My copy cost a buck, and it is filled with more than 150 illustrations by James Irving, mostly in color. The images in the book were strongly influenced by space artists Lucien Rudaux and Chesley Bonestell. The section on constellations was where I spent most of my time. Stars and Constellations also has chapters on planets, comets, the Moon, and meteors. There is even a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram plotting stars’ luminosity on a graph, which totally baffled my 8-year-old brain.

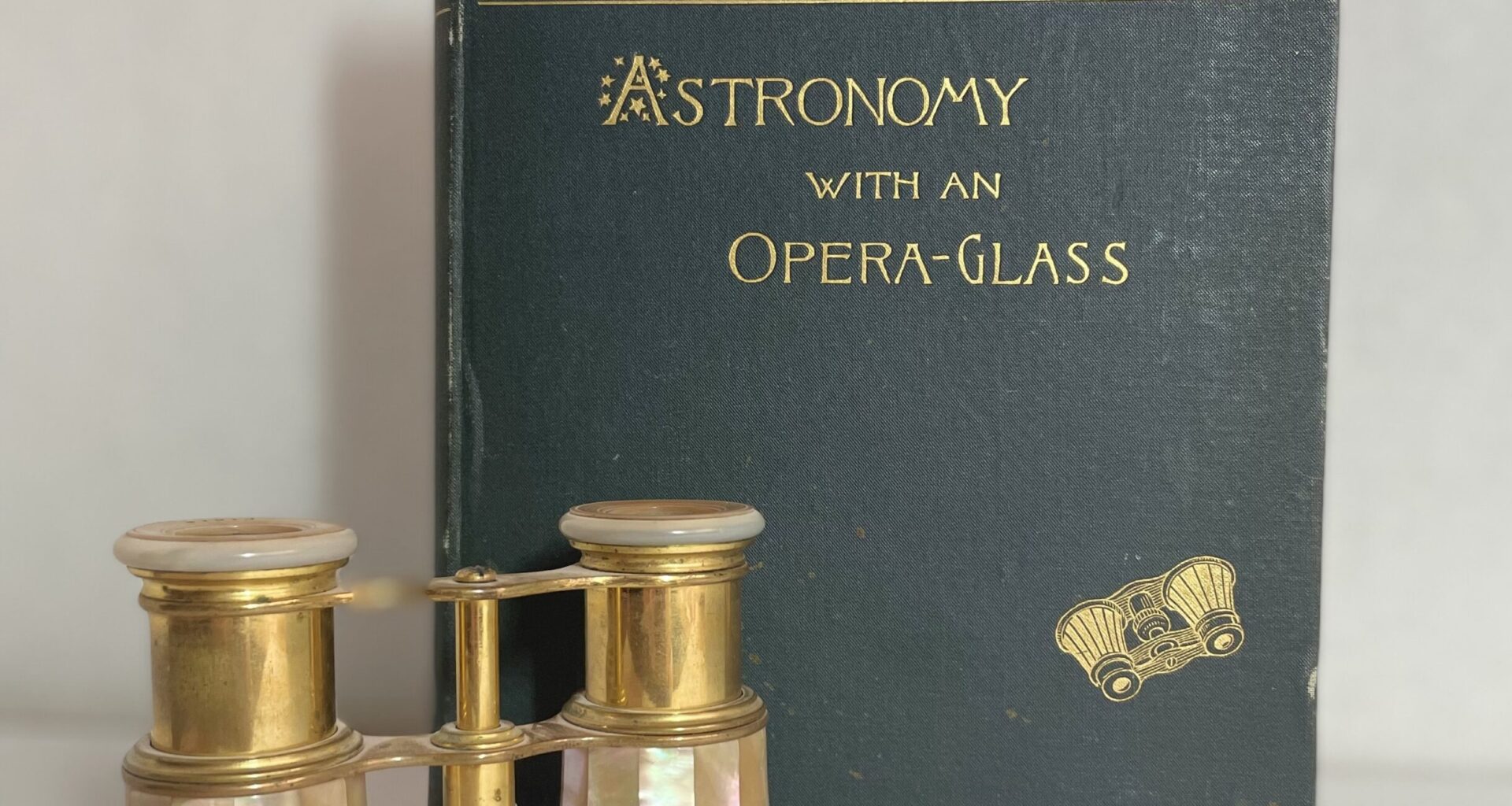

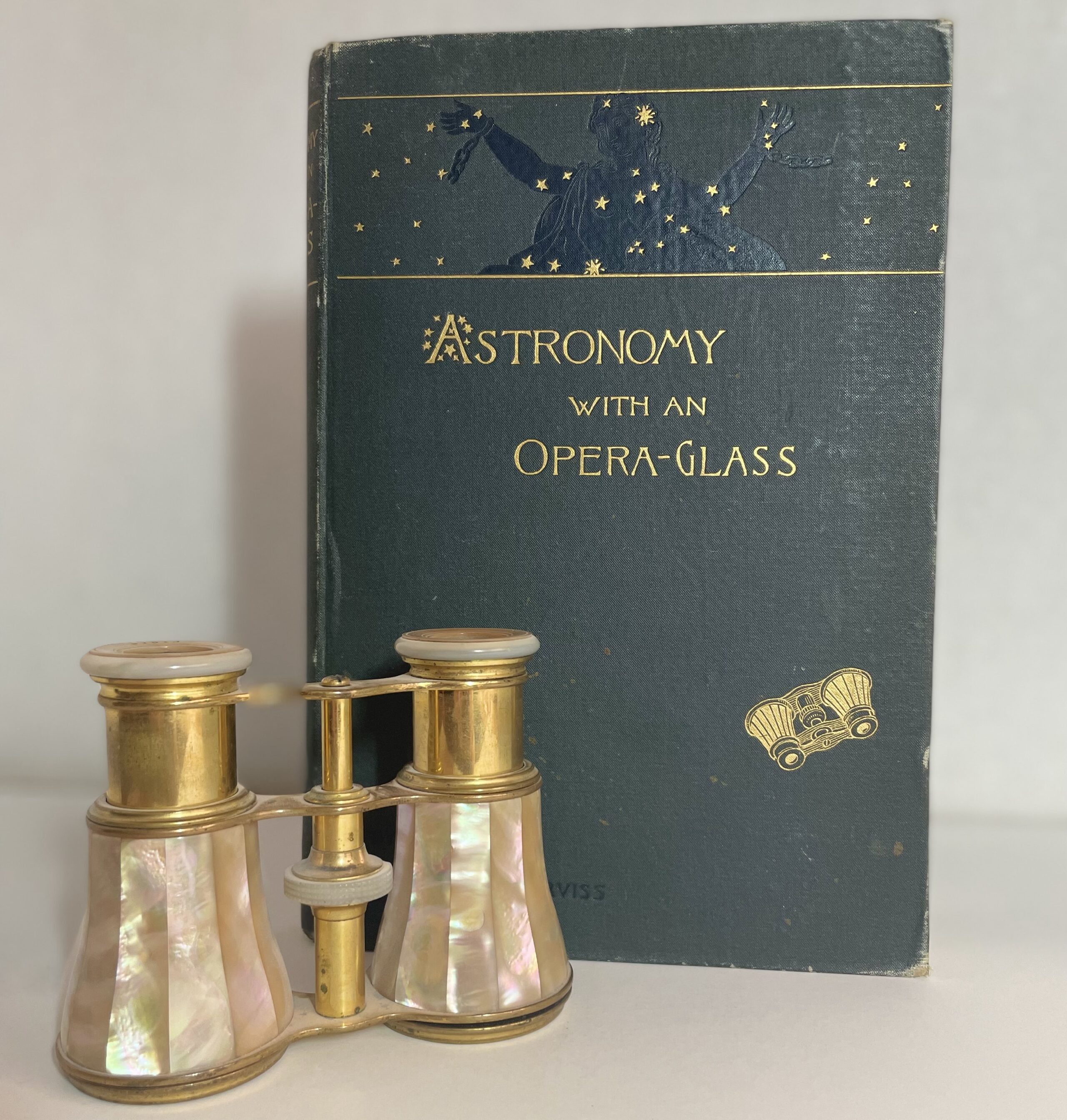

Not long after my mother gave me Stars and Constellations, I found a rather dog-eared copy of Astronomy With an Opera-Glass in the basement of our town’s old Carnegie library. The library was opened in 1902, and this book looked like it had been there the whole time. Written by Garrett P. Serviss in 1888, it was a popular beginner’s guide for many decades.

As a young amateur astronomer, I loved his colorful descriptions and flowery language, which brought sky observing to life. Serviss provided not only useful information, but also a sense of wonder and romance about the night sky. Almost forgotten today, Serviss became one of the most important popularizers of astronomy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Long out of print (although copies are easy to find), Astronomy With an Opera-Glass is still delightful to read and useful to beginners and seasoned observers alike.

For beginners

One of my favorite guidebooks measures a mere 3½ by 5¾ inches (9 by 15 centimeters). Despite its diminutive size, it made a huge impact on my developing interest in astronomy. The Observer’s Book of Astronomy by Patrick Moore was first published in 1962; my copy is from 1965. Moore wrote, “This book, however, is not written for the serious observer, but for the beginner.” His book is reminiscent of the Golden Nature Guide. This little volume covers all the basics, from equipment to constellations and planets, the Moon, and even a bit about the then-nascent space race. It is filled with black-and-white images and written in Moore’s straightforward style. It’s easy to read, and it was an early addition to his long list of astronomy books.

Moore was, by definition, an amateur astronomer — self-taught and never appointed to a formal academic position. The introduction of this book tells the reader, “The main requirements [for an amateur astronomer] are enthusiasm and patience.” This is good advice that has always stuck with me. In 1965, Moore published his guide Naked-Eye Astronomy. This month-by-month description of the night sky gives novice observers a “big picture of the yearly parade of stars and constellations.”

William Olcott’s Field Book of the Skies is a celestial guide that has been by my side for many years. An enthusiastic amateur and founder of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, Olcott first published In Starland With a Three-Inch Telescope in 1909 before gaining recognition with Field Book of the Skies in 1929.

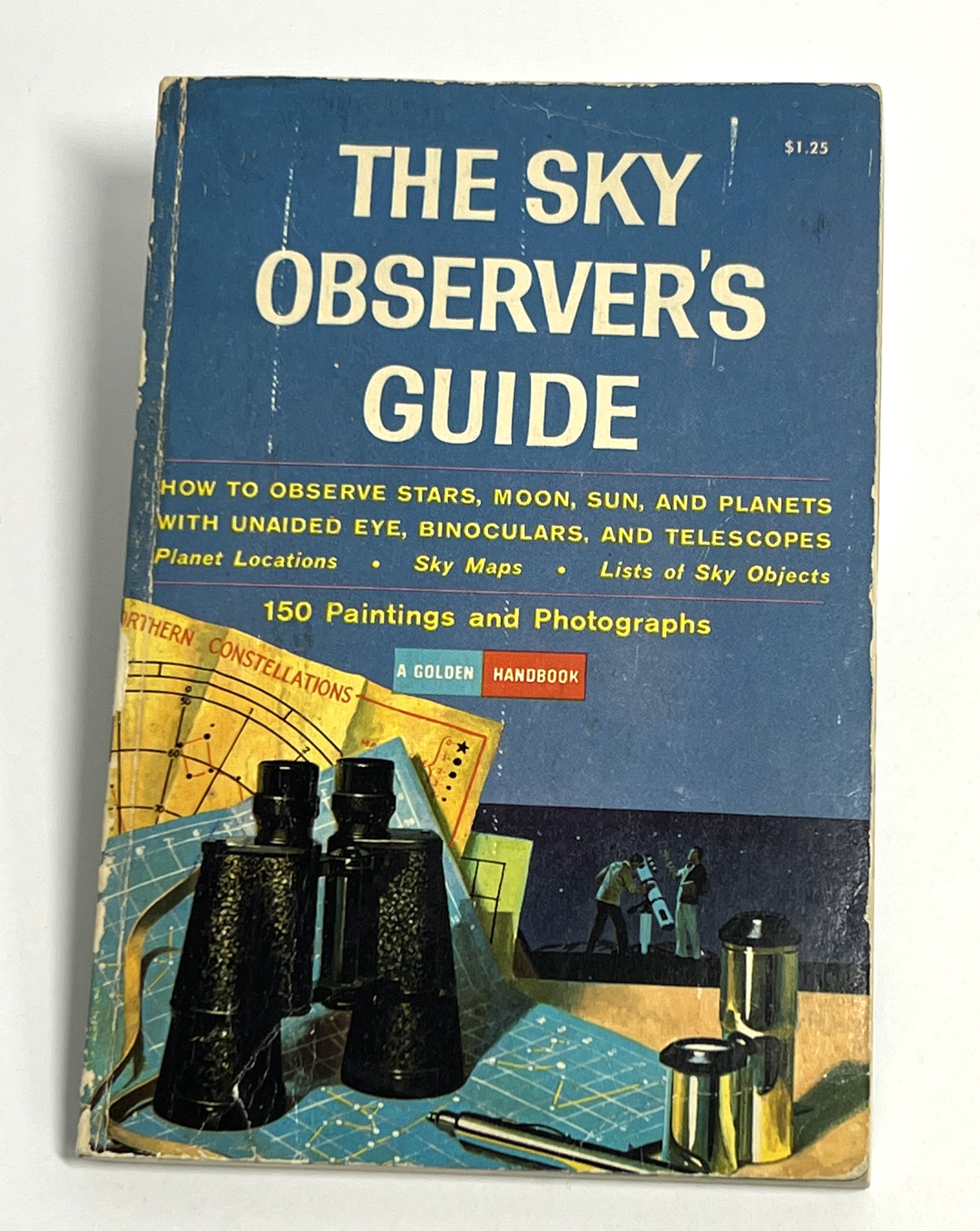

Credit: Raymond Shubinski

The bulk of Field Book is dedicated to the constellations in an extremely accessible layout. Arranged by seasons, each entry begins with a summary of the constellation followed by a section for the unaided eye and field glass (binoculars). Each section has an accompanying star chart. It then concludes with a chart and description of objects for small telescopes. The book provides a wonderful step-by-step tour through the sky. Field Book was revised by the astronomers Robert and Margaret Mayall in 1954 but has since gone out of print. The Sky Observer’s Guide, written by the Mayalls, was another of their contributions to the field.

Guideposts to the Stars by Leslie Peltier elevates the beginner’s guide to the level of near poetry. I read Peltier’s autobiography in the late ’60s and was entranced by the story of this amateur astronomer. Peltier wrote his guide, released in 1972, assuming the reader is a “total stranger to the nighttime sky.”

He begins the journey with 15 of the brightest stars, and guides the observer through the yearly panorama of constellations. Starting with spring and the star Vega (Alpha [α] Lyrae), Peltier weaves his own story into the descriptions of stars and constellations for a truly compelling experience. No matter how well I have come to know the sky, this is a book I still read for inspiration.

Leveling up

Beyond the basic guides to the night sky are those that take the novice into the world of more advanced observation. Patrick Moore wrote several useful guides, including Exploring the Night Sky With Binoculars. Published nearly a quarter-century after The Observer’s Book of Astronomy, it quickly became a go-to guide for scanning the sky at low magnification. I was a seasoned observer by the time I found this book, but it was still full of information I hadn’t seen elsewhere.

Credit: Raymond Shubinski

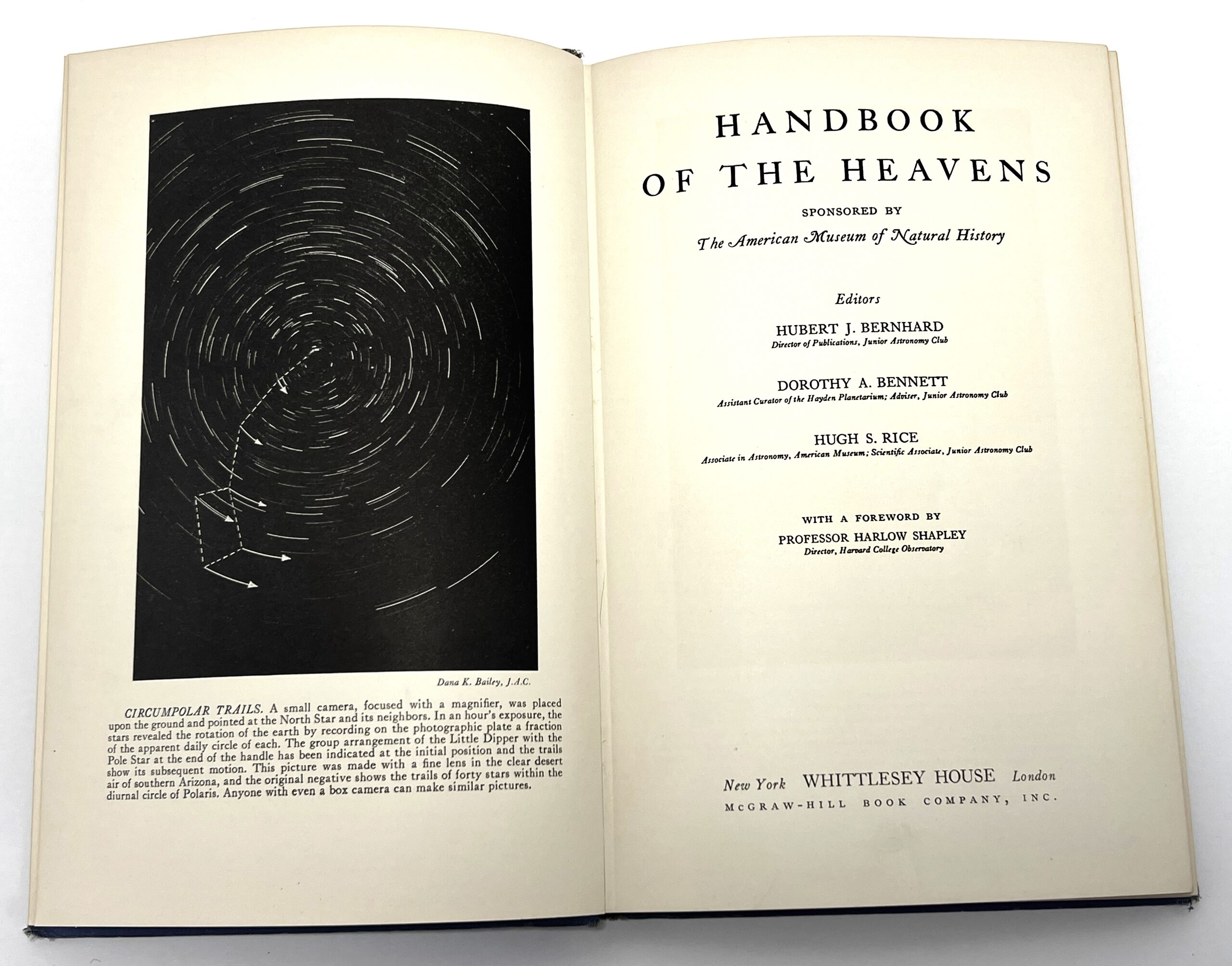

Handbook of the Heavens was another well-thumbed book I found at my local library. First published in 1935, this guide was sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and was a collaborative effort by both professional and amateur astronomers. Handbook is full of practical information on using telescopes to observe double stars, the Sun, the Moon, and the planets. I was especially drawn to the last chapter, called “Observational Scrapbook.” It includes tidbits of information about meteorites, coordinate systems, and why the Moon can be seen north of the zenith in Florida. In the early 1940s, the book was revised and enlarged as the New Handbook of the Heavens. Information was added on variable stars, sky phenomena, and darkroom work. Sadly, the “Observational Scrapbook” chapter was deleted.

As I developed a more technical interest in observing, I turned to James Muirden’s The Amateur Astronomer’s Handbook. Muirden is a British amateur astronomer who has published books on telescope-making, observing with binoculars, and more. This 1968 book is a great introduction to telescopes and other equipment. The sections on observing the planets are still useful and relevant.

When I got my first telescope, a small Tasco refractor, I turned it on the Moon. I used Dinsmore Alter’s Pictorial Guide to the Moon to guide my initial observations. Alter relates both history and physical aspects, making this more than just a guide to lunar features. I enjoyed his descriptions of the changing appearance of major lunar craters and what he terms “many peculiar aspects of the Moon’s surface.” Even though the explanations for those aspects have changed since the 1960s, this is still a wonderful guide to observing our nearest neighbor.

Beyond print

Credit: Raymond Shubinski

Not all beginner’s guides to astronomy are in book form. Planispheres are simple star maps that can be set for any time and date throughout the year. The planisphere is a direct descendant of the ancient astrolabe, reduced to its simplest form. Being a collector, I have a stack of these devices. They are made of plastic, cardboard, and even wood. They also come in every size you might want.

I bought my first (and still my favorite) at the Adler Planetarium gift shop in Chicago. It is easy to use and best of all, the stars glow in the dark! One of the most popular of these devices was the Barritt-Serviss Star and Planet Finder, first printed in 1906.

My most unusual guide was a vinyl LP of a sky lecture (one in a series) by Hubert J. Bernhard at Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco. It was the audio of a program touring the solar system. I ran across a magazine ad for the record, sent off the money, and received it a few weeks later. It seemed high-tech at the time. Recently, I found one on eBay to replace my original.

Obviously, I’ve dated myself with this list of guides that helped grow my interest in astronomy. My list could go on and would include Astronomy magazine, the Abrams Planetarium Sky Calendar, and even the Old Farmer’s Almanac, which actually remains more practical than most people think.

We want to hear from you

There are many great beginner’s guides I haven’t mentioned. Which guides helped you along your path of discovery? Email our editorial team (astronomyeditorial@astronomy.com) and tell us and other readers what inspired you.