Astronomers have been studying the sun for over 400 years, but Galileo was one of the first to document dark spots in the star. These observations challenged the general idea that the sun had the perfect spherical shape. Not only these discoveries, but many others, made Galileo one of the most revolutionary astronomers in history. Unfortunately, he did not live long enough to see what the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter found out during a routine fly-by over a nearby planet.

The sun is special: There’s an instrument specifically designed to study it

Since Galileo, the technology has advanced enough for astronomers to send probes to space, rovers to Mars, and track the sun’s 11-year cycle and study phenomena such as solar flares – something that could put an end to the world as we know it with just a small demonstration of its power. Observing the phenomena has not been easy due to the limited angles we are able to see from Earth, or by nearby spacecraft.

On the other hand, this could soon be a thing of the past with the newest way to collect data from the sun that the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter gathered while conducting a flyby. By accident, it revealed a part of our star that was previously inaccessible, and the new findings could change our understanding of its magnetic field, like Galileo did in the past.

New insights in the sun’s behavior: Galileo saw it first

For the first time since telescopes were invented and Galileo was looking to the sky, scientists can actually see the Sun’s poles, uncovering magnetic and structural details that were not expected. The Solar Orbiter made it possible by using a gravity assist during its February flyby of Venus, which tilted its orbit 17 degrees away from the Sun’s equator.

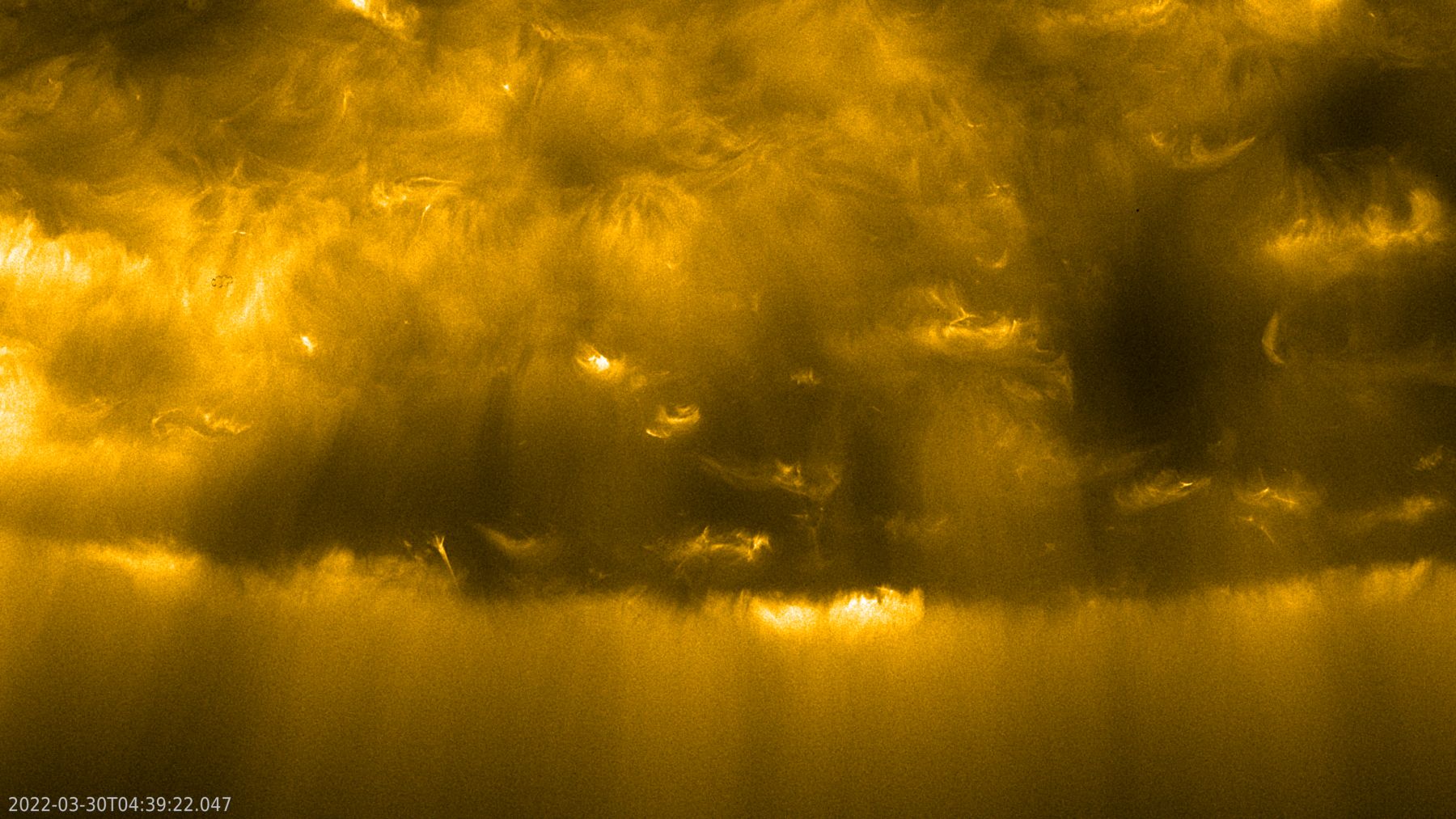

The images revealed the intensity of the Sun’s South Pole, really – something astronomers had no idea. Instruments like PHI, which maps magnetic fields, and EUI and SPICE, which observe the upper atmosphere and corona, collected data showing how magnetic activity sends charged particles streaming into space – similar to the process that brings ghost particles to Earth.

Careful when study the star: Its magnetic field is tricky

Unlike Earth’s mostly steady magnetic field, the Sun’s magnetic zones are always in motion. Smaller, active regions around sunspots and the poles help shape the star’s overall magnetic field. Most of the time in its 11-year cycle, this field acts like a giant bar magnet. But near the solar maximum – the Sun’s most active phase – the field flips, swapping north and south poles.

With Solar Orbiter’s unique perspective, scientists are seeing this flip happen for the first time – another huge step beyond the early observations Galileo made back in the 1600s. The spacecraft has also captured fresh images showing how different chemical elements move through the Sun’s layers. Using SPICE, which picks up specific frequencies of light called spectral lines, it tracks elements like hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, neon, and magnesium as they shift and flow at various temperatures.

Solar Orbiter immune to sun’s power: It traces from distant

For the first time, the SPICE team was able to track these spectral lines to measure how fast chunks of solar material are moving. These measurements show how particles get launched from the Sun as solar wind. Understanding these winds and eruptions better will help scientists predict how sudden bursts could impact life on Earth. A strong solar burst could disrupt satellites, throwing daily life into chaos. With over 10,000 satellites in orbit, even a small flare could have major consequences, but there’s one new technology that could use the power of the sun to help people to generate energy “directly from the source”.