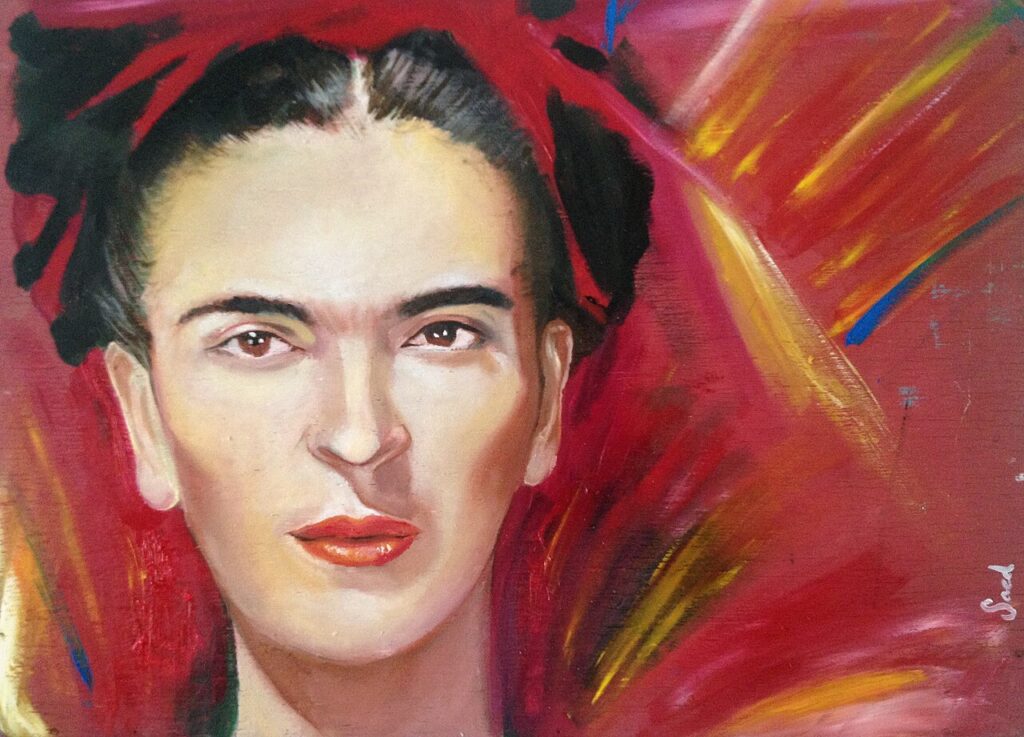

Psychiatrists have proposed a new personality called the “otrovert”, which refers to a person who is not an extrovert or an introvert. Credit: Saed de los Santos – CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Psychiatrists have proposed a new personality called the “otrovert,” which refers to a person who does not look inward like an introvert or outward like an extrovert. Instead, the otrovert orients differently from those around them. The new label is being put forward by psychiatrist Rami Kaminski as a distinct, and potentially advantageous, form of temperament.

Kaminski initially described the idea in New Scientist, as well as the upcoming book, The Gift of Not Belonging: How Outsiders Thrive in a World of Joiners. He claims he has seen the trait in patients, as well as in himself.

The psychiatrist coined the term from the Spanish otro, meaning “other,” and the suffix “-vert,” borrowed from psychological language describing orientation.

The ‘otrovert’ personality started as a joke

In an interview with New Scientist, Kaminski said: “In the early stages, it was kind of a joke in the team,” but after systematic observation, he said, what began as a joke became an actual viable hypothesis. Under the new label, they proposed that, some people habitually face a different emotional direction than those around them.

Kaminski and other proponents of the new personality describe otroverts as emotionally independent, resistant to the social impulse to “pair” with the emotions of people nearby, what he dubs the “Bluetooth phenomenon,” and inclined toward originality. They are, he said, the kind of thinkers who can spot “the fanaticism of a hive mind long before most people can.”

He traces his own recognition of the trait to childhood. Wearing a scout uniform and repeating the pledge, he wrote, he “felt nothing” while other children were visibly moved, a small moment that, in hindsight, marked emotional detachment rather than indifference, he said.

Historical figures like Frida Kahlo and Franz Kafka may have been otroverts

According to Kaminski’s writings, there are some historical figures he believes exemplify this newly proposed personality. He claims Frida Kahlo, Franz Kafka, Albert Einstein, and George Orwell may all have been exponents of this personality.

“Some have seen it as a psychological problem to be treated,” he wrote, and the cultural premium on belonging can make adolescence particularly fraught for those who do not easily affiliate with peer groups. His book’s title, however, reflects the central claim, which is that the personality trait is not only a burden but a potential gift. He also describes the personality as a predisposition toward indepedent thinking and creative problem solving.

The otrovert personality departs from Jungian categories of introversion and extroversion by suggesting a different axis of social orientation. Kaminski has called for more research to be done to identify the trait’s developmental origins and underlying mechanisms. While the term is new and its reception among clinicians and researchers remains to be seen, Kaminski says recognizing the pattern could change how therapists and educators respond to people who do not fit neatly into existing personality molds.