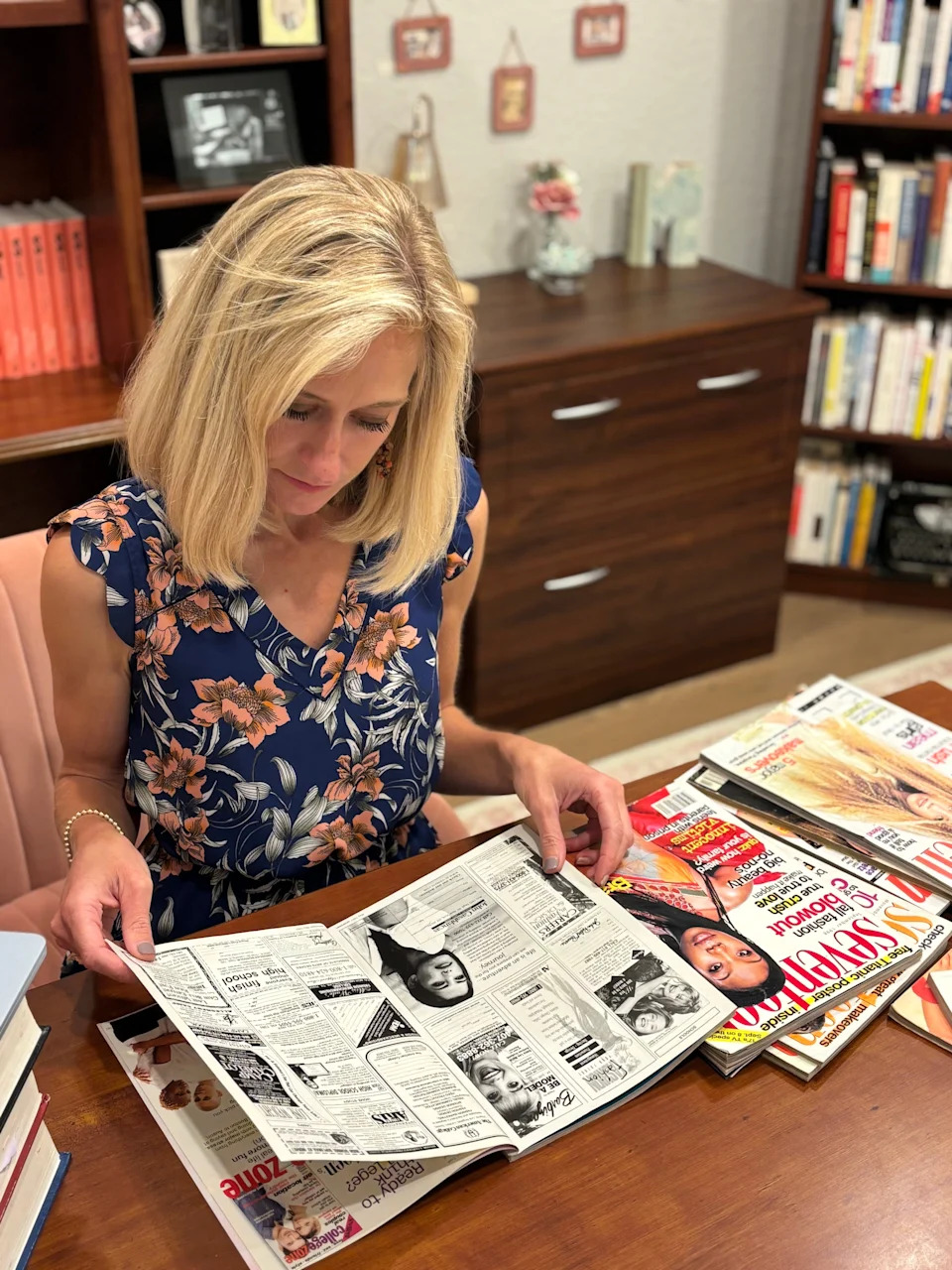

The first time I remember seeing weight loss ads, I was 11 years old. As a child of the ’80s and ’90s, I had a subscription to Seventeen magazine, which featured ads about weight loss and “fat camps” for kids as young as 7. “Lose as much as 40 pounds and learn to keep it off!” one of them claimed. “This summer, you can become the person you always wanted to be.”

I thought of that ad this summer, while streaming a Disney+ movie with my kids on a rainy day in June. In the middle of watching “Home Alone” (a family favorite that my 7-year-old son and 9-year-old daughter will gladly watch any time of year), a commercial for GLP-1s popped up on the screen.

I quickly turned down the volume and started talking to my kids about the scene we had just watched, in hopes of diverting their attention away from an ad that told viewers they could lose 15% of their body weight. But the same GLP-1 commercial aired later on, and I was reminded that no matter how many times I try turning down the volume, the din of weight loss ads will always ring loudly. I reached out to Disney+ multiple times for comment.

These ads seem to be more prevalent now than ever, and their target audience knows no bounds. Are we really at the point where we need to be showing GLP-1 ads in the middle of a Disney movie? And why aren’t more people speaking out about their potentially harmful impact on kids?

“The first time I remember seeing weight loss ads, I was 11 years old,” writes Mallary Tenore Tarpley. “As a child of the ’80s and ’90s, I had a subscription to Seventeen magazine, which featured ads about weight loss and ‘fat camps’ for kids as young as 7.”

Some would argue that these ads are necessary at a time when an estimated 42% of adults and 19% of children are considered obese. Many point to the benefits of these “miracle drugs,” saying they are our best weapon in the proverbial fight against obesity.

But the relentless barrage of ads makes us believe that all of us should be striving to make our bodies smaller at all times – and that we’d all be happier, healthier and more attractive if we did so. As someone who nearly lost my life to a childhood eating disorder, I know this is simply not true.

The weight loss ads I consumed as a child didn’t solely cause me to develop anorexia, but they were one of many contributing factors, and they no doubt exacerbated my disordered thoughts and behaviors when I was at my sickest. Even when I was clinically underweight, the ads made me feel as though I was never thin enough.

I don’t want my kids growing up to feel the same way, especially knowing that they have a higher risk of developing anorexia because of my own lived experience. We can’t control genetic risk, and in the face of a $425 billion weight management industry, we may feel as though we have little control over environmental risks. We may not even consider weight loss ads to be risky in the first place because they’re so ubiquitous as to seem innocuous.

But such ads have been shown to support pernicious behaviors and beliefs around food, exercise and body image. They’re also known to cause harm to people with eating disorders and can contribute to relapse, and we’re learning that GLP-1s may do the same.

Kids are all too often exposed to GLP-1 ads without context, but not without consequence. We’ve gotten better about drawing attention to social media’s adverse effects on adolescents, but we’ve been a lot quieter about the effect that weight loss ads can have. And this is a problem, especially given that there aren’t guardrails or parental controls preventing youth from viewing this content.

In case you missed: Serena Williams, the Ozempic craze and what it says about body image

If we want our children to be critical consumers of such ads, we need to teach them what many of us never learned growing up: That the messages they’ll inevitably hear about weight loss and the thin ideal are rooted in fatphobia (a system of oppression that discriminates against people in larger bodies) and in diet culture (a system of societal expectations that values thinness.)

This is true to the point where it’s more the norm than the exception for adults to feel bad about their bodies – a phenomenon that researchers refer to as “normative discontent.” Children are no exception; studies show that kids as young as age 3 have body image concerns. Pro-thin/anti-fat implicit weight biases have also been on the rise, suggesting that diet culture’s messages are increasingly shaping our subconscious.

We’re not customarily taught to spot diet culture or to call it out. But as a mother in recovery from anorexia, I think we need to teach our kids to do so – both as an important form of eating disorder prevention and as a means of helping kids realize they don’t need to let societal expectations dictate how they feel about their bodies. When I was looking at those Seventeen magazine ads as an 11-year-old, I wished someone had told me, “That’s diet culture trying to tell you that you need to be thinner, but you don’t have to listen to that message. No child your age should have to.”

Knowing that my children are approaching the age that I was when I developed my eating disorder, I want to help pave a different path forward for them. Lately when weight loss ads have come on the TV or radio, I’ve been letting my kids know that they’re going to grow up to see a lot of ads like this because of diet culture. (Ironically, I also had to reiterate this when we stumbled upon “lose belly fat!” pop-up ads while scrolling through a personal essay I wrote about how I’m helping my kids navigate body image.)

‘We’re all overcompensating’: Why so many LGBTQ community members struggle with body dysmorphia

I talk with my children about diet culture in simple terms, by referring to it as a set of messages that will try to make them believe that thin bodies are “good” and fat bodies are “bad.” I tell them that this isn’t true, and I repeat a refrain that I’ve said aloud for many years: “All bodies are worthy of respect, no matter how short or tall, no matter how big or small.”

I share this refrain with an acknowledgment that it can be hard to turn this thought into a belief, partly because it runs so contrary to the fatphobic messaging most of us have heard our entire lives. And I share it as someone who hasn’t had to face the bodily disrespect and chronic weight stigma that so many people in larger bodies do.

In the face of pervasive weight stigma, we can’t expect everyone to unconditionally love their bodies. But we can teach the next generation that their worth is not dependent upon their weight. We need to help kids recognize this so that when they inevitably see weight loss commercials, they won’t fall for the misguided messaging behind them. Against the backdrop of advertisements that try to downsize us, we need to help kids realize that it’s OK to take up space.

If you or someone you know is struggling with body image or eating concerns, you can call The National Alliance for Eating Disorders‘ clinician-run helpline from 9 a.m. until 7 p.m. EST at (866) 662-1235. If you are in crisis or need immediate help, please text “ALLIANCE” to 741741 for free, 24/7 support.

Mallary Tenore Tarpley is a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of the memoir “SLIP: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: GLP-1 weight loss ad plays on Disney+. We need to talk to kids.