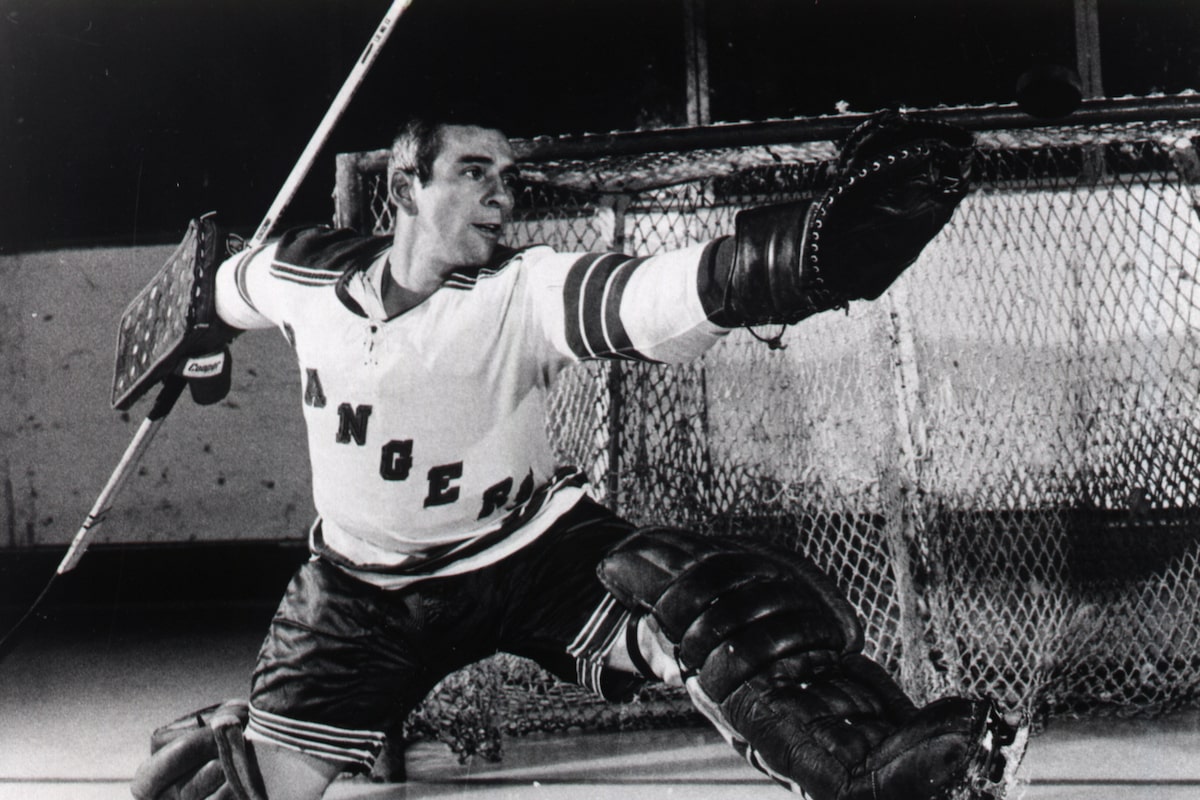

Eddie Giacomin, clad in goalie pads, frequently left the security of his goal crease to grab a loose puck, or to deliver a bodycheck to an unsuspecting forward.

The wandering goaltender, nicknamed Fast Eddie, backstopped the New York Rangers and the Detroit Red Wings for 13 seasons, building a hall-of-fame career from unpromising beginnings.

Mr. Giacomin (pronounced JACK-oh-min), who has died at 86, helped make the Rangers playoff contenders in the mid-1960s after the club spent a long spell as league doormat.

His peripatetic play drove his coach and hometown fans crazy, as early in his career he surrendered easy goals into an abandoned net. But as he refined the style, he worked almost as a third defenceman, thwarting attacking teams seeking to dump and chase the puck.

“If I have the opportunity to hit somebody, or to get the puck and pass it out, then I will do it,” he said in 1974. “I do a lot of hollering in the game. I try to get everybody as up as I can.”

The goalie’s rocky introduction to New York’s infamously critical fans included one game in which he was pelted with debris. Over time, he came to be a fan favourite, and his return to Madison Square Garden after being lost on waivers led to a remarkable demonstration in the stands.

He also was photographed in action on the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine and made a memorable appearance on The Tonight Show to tutor host Johnny Carson on stopping pucks flicked by Bernie (Boom Boom) Geoffrion.

That Mr. Giacomin had a professional career at all seemed unlikely when he was a teenager, as he failed several tryouts before suffering serious burns to his lower body in a household accident.

Ed Giacomin, left, pokechecks Boston Bruins’ Phil Esposito as he fires a shot during a game at Boston Garden, in March, 1969.A.E. Maloof/The Associated Press

Edward Giacomin, who was born on June 6, 1939, in Sudbury, Ont., was the middle of five children with two older brothers and two younger sisters. His parents, Cesira (née Bartolucci), known as Cecile, and Antonio, known as Tony, had both immigrated to Canada from small towns north of Venice, Italy. Tony worked as a construction labourer, eventually becoming a foreman.

As a teenager, Ed followed his older brother, Rolando, known as Rolly, in being a goaltender. He also played centre field for a baseball team in nearby Copper Cliff in the summer and semi-professional football as quarterback for the Sudbury Hardrocks in the fall. He was offered a combined baseball and football scholarship to a California college, though he would have had to complete another year of high school. Instead, he accepted an invitation to try out for a junior team in Hamilton, only to be rejected by the club for a second time.

He returned to Sudbury where he took a job as a mechanic’s helper at a chemical plant, paying $2 a night to cover the cost of ice to play games in an amateur commercial league. They bought their own uniforms and equipment. Games started at 11 p.m., the only time the rink was available.

His break came when his brother got a desperate call ordering him to report to a minor professional team in Washington, D.C. Rolly was working night shift for the mining company Inco and was unavailable, so told his kid brother to go in his stead.

The slight, teenaged goalie seemed dwarfed by the pads he carried over his shoulder when he arrived at Uline Arena in Washington to report to Presidents playing coach Andy Branigan, as Mr. Giacomin recounted for Paul Rimstead in a magazine feature published in 1967.

“I walk up to him and say, ‘Mr. Brannigan?’ He looks at me as if I’m bothering him and says he’s busy.

“But I came all the way from Sudbury to play for you.”

“Oh,” the coach said, “you’re Rollie Giacomin.”

“Uh, no sir. I’m Eddie. Rollie’s workin’ shift work.”

Chicago Blackhawks’ Stan Mikita puts the puck past New York Rangers goalie Eddie Giacomin as teammate Bobby Hull skates past during a game in New York, in November, 1965.The Canadian Press

The coach had the young goalie sit on the bench for several Eastern Hockey League games until the visiting Clinton (N.Y.) Comets needed a replacement when their starting goaltender got injured. He lent Mr. Giacomin to the Comets for one game, and the rookie surrendered two goals in a loss, but made 27 saves, several of them spectacular. He then went on to win three games for the Presidents.

Shortly after returning home in the 1959 off-season, Mr. Giacomin suffered serious burns to his legs and lower body when a hot frying pan filled with grease was knocked off the stove at the family home in Sudbury. He spent two months in hospital undergoing skin grafts.

After two seasons as a suitcase goalie for the Comets, Johnstown (Pa.) Jets, Montreal Royals and New York Rovers, Mr. Giacomin at last became the first-string netminder for the Providence Reds a year after he had first failed a tryout with the American Hockey League club. (When he was called up on a Friday early in the season, the Rovers president told reporters he expected the castoff goalie to be back by Wednesday.)

After five seasons in Rhode Island, he was at last regarded as a prospect for the National Hockey League with four of six teams interested in his services. The New York Rangers sent four players to Providence in exchange for the goalie.

Mr. Giacomin competed for a permanent roster spot against veteran Don (Dippy) Simmons, who had won three Stanley Cups as a backup with the Toronto Maple Leafs, and Cesare Maniago, a tall goalie from British Columbia also of Italian Canadian heritage.

The Rangers were woeful in 1965-66. Some blamed the goaltending. When utility forward Lou Angotti was traded midway through the season, he fired a departing shot, saying, “You work like hell and the guy in the net gives it away.” All three goalies would be demoted to the Baltimore Clippers for part of the season.

From left to right, Former New York Rangers Rod Gilbert, Eddie Giacomin, Mike Richter, Mark Messier, Brian Leetch, Adam Graves, Andy Bathgate, and Harry Howell at Madison Square Garden in February, 2009.Mike Segar/Reuters

Mr. Giacomin emerged as the club’s starting goaltender the following season despite suffering a humiliating failure and earning lusty boos from New York’s notoriously tough fans. The Rangers were cruising to a victory with a 3-1 lead with less than two minutes to play against Boston on Nov. 9, 1966, when the Bruins pounced for two goals in 55 seconds. The crowd at Madison Square Garden pelted the home goalie with eggs, coins, paper cups, orange peels and crushed ice-cream containers, all of which he shovelled into the back of his goal so the game could finish quickly.

“I thought it was wicked, the things they threw at Giacomin,” said Emile (The Cat) Francis, New York’s coach and general manager, himself a former goalie.

Over time, Mr. Giacomin’s wanderlust forays into the corner and out to the blue line became more calculated, less risky. As well, his weaknesses in goal were identified – stick blade not level to the ice, short side not properly protected – and corrected through instruction by Mr. Francis, and he became a formidable goaltender.

The Rangers qualified for the playoffs for the first time in five seasons, only to be swept in four games by the Montreal Canadiens, who would go on to win the Stanley Cup.

At 5-foot-11 (180 centimetres) and 180 pounds (81 kilograms), the bare-faced goaltender was a lean, acrobatic figure. Over the years, the strain of goaltending left him looking ever gaunter, with sunken cheeks and circles under his eyes, an effect made even more pronounced by the premature greying of his hair, which eventually turned as white as the painted ice on which he played.

While he wore a mask during practice, Mr. Giacomin only began wearing one during games at the start of the 1970-71 season, a campaign in which he paired with backup Gilles Villemure to win the Vezina Trophy as the league’s top goaltenders.

The Rangers made the Stanley Cup finals in 1972, powered on offence by the GAG (Goal-a-Game) Line of Jean Ratelle, Vic Hadfield and Rod Gilbert with Brad Park anchoring the defence. The Bruins defeated the Rangers in six games. Mr. Giacomin, hobbled by a knee injury suffered earlier in the playoffs, would never get closer to winning the Stanley Cup.

In 1975, after the Rangers lost four games by an aggregate score of 23-4, the team began a clear-out sale. The 36-year-old goalie was shocked when told Detroit grabbed him for the waiver price of $30,000.

“It was like I had fallen through a trap door and was tumbling in space,” he told the New York Times.

Eddie Giacomin at an exhibition game between the NHL Heroes of Hockey team, wearing red and white, and the New York Rangers Heroes team in January, 1994.Jim Sulley/The Associated Press

He quit goaltending and took a front-office job with Detroit early in his third campaign with the club. In 610 NHL games, he had a goals-against average of 2.82 with 54 shutouts. In 65 playoff games, his average was 2.83 with one shutout.

After retiring as a player, he bought the “dumpiest bar in the county” and named it Eddie Giacomin’s Sports Den. He coached the hockey team at Brother Rice High in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., where both of his sons played. He also served as a goaltending coach for three NHL teams and provided colour commentary on television.

Mr. Giacomin died in Birmingham, Mich., on Sept. 14. He leaves his daughter, Nancy Schwartz; sons, Mark Giacomin and David Giacomin; 11 grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; and a younger sister, Gloria Giacomin. He was predeceased by brothers Giglio, known as Giggs, who died in 2008; and Rolando, who died in 2024; as well as by sister Aida, known as Ida, who died in 2015.

Mr. Giacomin was named an NHL end-of-season All Star for five consecutive seasons (twice to the First Team, thrice to the Second Team). In 1987, he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame and two years later the team retired his No. 1 sweater in an emotional ceremony.

But the greatest tribute he experienced came shortly after he was let go by the Rangers in 1975.

His first game as a Red Wing happened to be at Madison Square Garden. As he skated onto the ice, the fans began their familiar chant of “Ed-dee! Ed-dee!” They drowned out The Star-Spangled Banner as they rooted for a visiting goalie for the first and only time in the city’s history, applauding their discarded hero.

“I stood in the crease and looked into the glass during the national anthem, and it was too much,” Mr. Giacomin told Joe Sexton of the New York Times 14 years later. “I’d seen those people for years. They kept up the applause, not easing up. The tears came because I couldn’t understand why I had been let go, couldn’t figure out what I had done wrong.”

After holding his face in his bare hands and wiping his eyes, the goalie backstopped his team to a 6-4 win, Detroit’s first victory on Madison Square Garden ice in five years.

The chant “always sent chills down my spine,” Mr. Giacomin said after the game. “Now I’ll never hear it again.”

You can find more obituaries from The Globe and Mail here.

To submit a memory about someone we have recently profiled on the Obituaries page, e-mail us at obit@globeandmail.com.