As I sat on a plastic chair in the starkly lit entrance room of a mental health hospital, a locked door on either side, I tried to track how I’d got there. The security guard behind me began streaming a football match on his phone loudly while I stared ahead, tears dripping on to the shirt I’d worn to work that day.

I had been sent to hospital an hour ago by a nameless man when I called the NHS crisis team, telling him that I felt suicidal. It was the sixth time I’d called but the first time I’d been sent to hospital. I was there to be assessed, monitored and, ultimately, kept safe.

Things began to unravel last winter when, at the age of 36, a lifelong, amorphous sadness that I decorated with jokes and deflection had blistered into something that roved and churned. Because the sadness had always ebbed and flowed I was good at continuing to function — proud of it, even. I socialised, moved house and held down my job, even as its river carved a widening path through me.

• Read more expert advice on healthy living, fitness and wellbeing

I was still living my life, or at least a performance of it. But over a period of months I began to disappear from the world in quiet ways. I sat in pubs with friends, slipping away in plain sight to some unreachable place. The more I smiled through it, the further away daylight seemed. I woke in the mornings with an ache in my chest and was hit by waves of hopelessness so intense that I lay face down on the floor, before standing and dressing for work.

The first phone call I made to the crisis team was in December. Walking home, I felt a sudden fear — and then clarity, that I shouldn’t be alone. When the woman asked why I was calling, I told her I didn’t want to be alive any more. When she asked how long I’d felt that way, I said most recently, several months. She asked whether I’d tried to take my own life in the past three months, and when I said I hadn’t, told me I wasn’t eligible for support from their team on that basis. I didn’t call again for some time.

The following month, however, returning home from the office, I stood, looking around my flat, and was engulfed by dread. I couldn’t imagine a time when I wouldn’t feel like this. An older man answered the call and, after a few questions, said he was worried about me. He gave me the address of the nearest mental health hospital and offered to send an ambulance. I cycled there instead: an out-of-body experience, as street lights passed silently overhead.

Once inside the hospital’s waiting room, my phone charger was removed (“for my own safety”) and a nurse checked my vitals. I still remember the feel of her papery hands as she took my blood pressure, the comforting squeeze on my upper arm as we sat, listening to the machine’s whirr. I felt relieved that she knew I was here. Relieved, in a way, to have admitted defeat.

• Grieving father leads overhaul of suicide risk assessment system

I tried to turn my chair to watch a couple rattling around Fuerteventura on A Place in the Sun, before realising it was nailed to the floor. The windows were barricaded shut. A man paced agitatedly back and forth beside me, and I felt in that moment that I had walked through a door that separated me from my life until now and the people in it — the version where I coped.

After an hour I was seen by a doctor. We sat under a flickering lightbulb on purple, plasticky sofas and he asked, “Why do you think you feel suicidal now?”

It was a question that I couldn’t easily answer. A long-term relationship had ended. I felt isolated. But this felt more like a reckoning — the fruition of something that began a long time ago, demanding to be acknowledged. I had been processing childhood trauma with a private therapist and had a diagnosis of CPTSD: complex post-traumatic stress disorder. I still believe it has been the right thing to do, but I do also think that exposing those roots brought with it a level of sadness that has felt at times unbearable.

I stared at a print of a waterfall behind his head as he continued.

Had I made plans? Yes.

What were they? I heard someone else’s voice falling out of me as I described them, detached — then shocked.

Did I think I could keep myself safe? I wasn’t sure.

What about a support network? That was more complex. Friends knew I’d had depression but not the full story. This new, cavernous sadness felt monstrous and I didn’t want anyone to see it.

The doctor recommended I stay but, as there were no available beds, offered me a sofa in the waiting room. I listened to a woman shouting in distress somewhere down the corridor. It was late now and, exhausted, I was referred to the NHS home team for two weeks of safety check-ins and went home on the condition I saw a GP the next day to discuss medication.

Like many, I’ve grown resigned to the limitations of a stretched NHS, but still I found some of what unfolded over the coming months shocking. The feeling throughout was that staff at best didn’t know how to treat me, but at worst didn’t believe me.

• Psychiatric staff ‘had no concerns’ about girl before she died

Sitting in my flat, home team staff often made comments like “you don’t seem depressed” and “your place is very … clean” — they were used to a certain face of depression. It made me feel invalidated and alone. One suggested I might enjoy Wednesday on Netflix; presumably because, like its titular Addams Family character, I too was a sad girl with brown hair. Another, after I said I’d been experiencing suicidal thoughts that morning, told me everything would be fine if I could “learn to look on the bright side”. I was frequently asked why I hadn’t “actually gone through with it”, the tone often bored, as if people failed to grasp that people generally don’t want to die, they just need help to envisage a way to live that feels bearable.

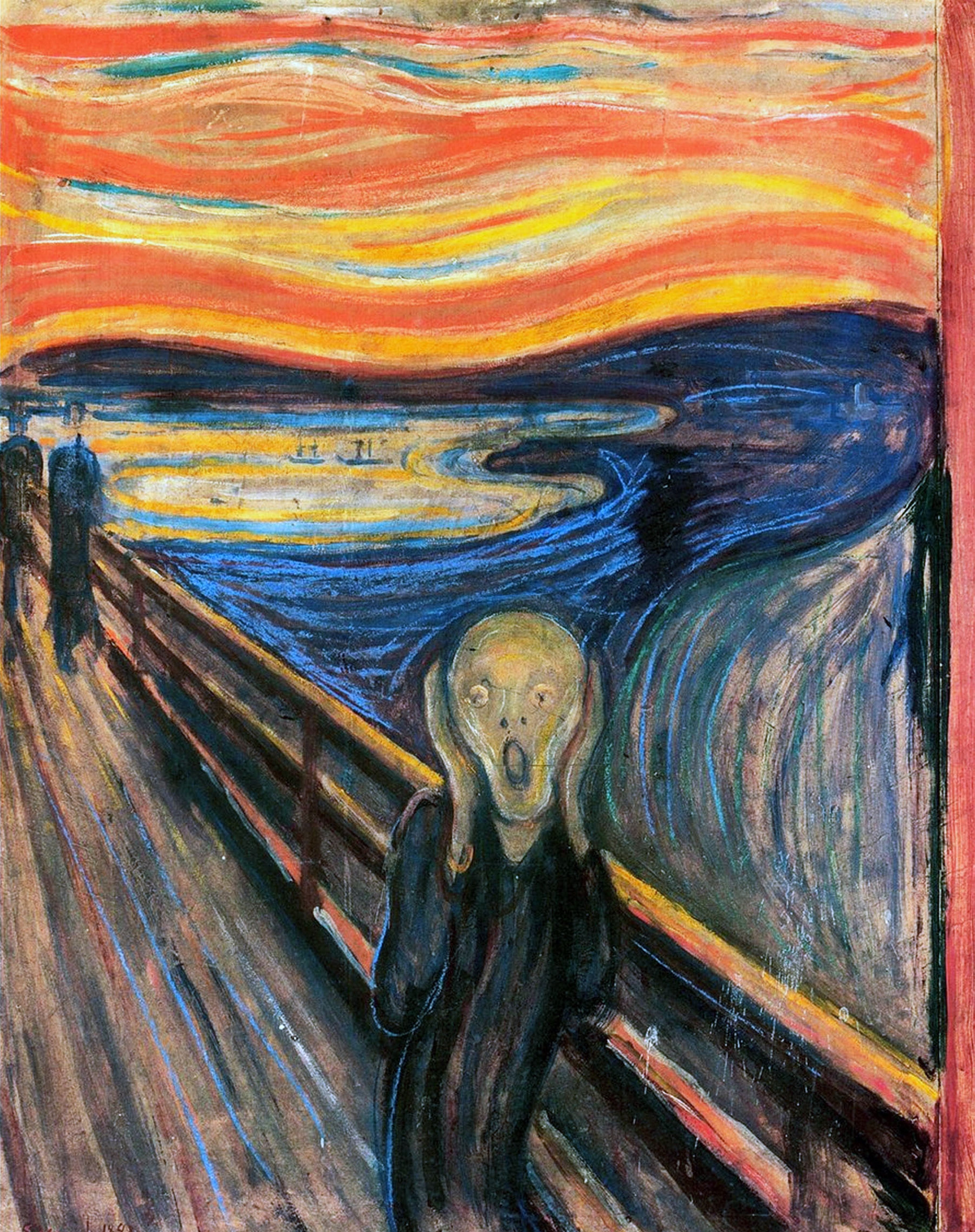

Other remarkable occasions included the time a crisis team member asked if I could stay with my parents and, when I told her my mum had died, said, “I’m sorry. But the thing is, everyone does die — so at least you’ll see her again soon.” Or when, in hospital, I was given two pictures to colour in: one, a rainbow emblazoned with the words “keep calm and dream!”, and another, a cartoon version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Which did actually make me laugh. As did the appointment I had with a psychiatrist who, because our room had been double booked, suggested we do laps of the car park, ending up standing beside the wheelie bins to discuss my history of suicidal ideation.

“I was given two pictures to colour in: one was a cartoon version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream”

GETTY IMAGES

Harder was the irritation and contempt shown by some staff, such as the nurse who, when I said I wasn’t on antidepressants, asked with no further context, “Why do you think you’ve ended up back here, then? If you won’t comply with treatment?” I told her she was giving big asylum energy — she didn’t laugh.

After two weeks with the home team, they said I’d be discharged in person. In the end, this happened over the phone — I don’t know why. It was one of the kinder team members, and my throat clenched and ached as I tried not to cry, feeling suddenly childlike. “I can tell you aren’t OK,” he said, which was true, but it made no difference. “It’s unfortunate,” he continued, clearly uncomfortable, “because according to protocol I do need to sign you off.”

He asked me to reconsider the antidepressants I’d been prescribed — something I’d resisted so far as I’d reacted badly to the same ones in the past and had been told they were the only option. I said goodbye and hung up, cast adrift, the air in the room calcifying around me.

Over several months I returned to the same hospital four times. I didn’t know in those moments — when I stared numbly into the mouth of a vast, yawning cave — what else to do. Friends urged me to confide more and I did, to a point. But often it felt too much to ask them to hold. I felt a wave of grief every time I responded to a text inviting me to stay with various excuses followed by, “I’m fine.”

The last time I called the crisis team, the voice was that of the older man who’d sent me to hospital on my first visit. We recognised each other and I thanked him for helping me. “That’s OK,” he said gently as we sat on opposite ends of the line, “you were easy to help.”

I’ll always remember his kindness, along with that of a handful of others. I knew he truly wanted to help. But the fact is, the system is broken. I often felt more hopeless, isolated and resigned after contact with the NHS, not less. I recently found a note in my phone that I’d made after the first call that just read: “Felt like confirmation my life didn’t matter.”

• When grief turns to madness — and medicine makes it worse

I know several women my age who have had similar experiences — two NHS doctors have said none of what I’d told them was surprising.

What I felt that first night in hospital was defeat but I now realise it was acceptance — that I couldn’t navigate this alone. And I have begun to accept more help. Still, I have felt afraid that by telling people, I will become something other in their eyes.

I said this to one friend recently as we sat on her sofa. “You are exactly the same person,” she said, handing me one of her baby twins, “and we’re family. People need each other, and I will need you. At the end of the day, what else is there?”

I didn’t want the people I loved to see me differently — and, inevitably, in some ways they now do. It has been exposing and destabilising. But it has also made me feel known and loved in a way I had not experienced before. It has felt like the opening of a window and has saved my life. Not something I will ever be able to say, sadly, of my — now coloured in — portrait of The Scream.

The writer has chosen to be anonymous