Bangladeshi businesses are paying higher costs when sending goods to India and bringing in industrial inputs from the neighbouring country amid retaliatory non-tariff measures imposed by Dhaka and New Delhi.

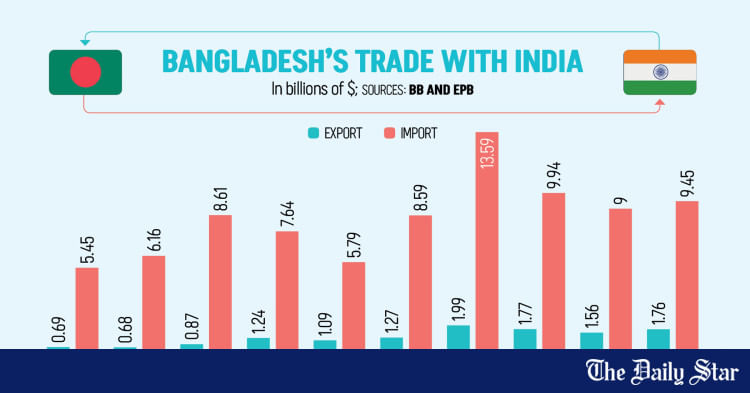

Annual trade between the two countries crosses $15 billion. India, after China, is the second largest source of commodities and raw materials for Bangladesh.

Businessmen say costs have soared by as much as 20 percent, mainly because goods are now being rerouted through Chattogram port, as non-tariff restrictions have choked movement through nearly a dozen land ports.

The commerce ministry said it has urged New Delhi to hold talks on the barriers, which are measures other than customs tariffs regulating imports or exports, but it is yet to receive a reply.

The current trade strain began in early April this year when India suspended transshipment facilities for Bangladeshi exports to third countries.

A week later, Dhaka suspended yarn imports from India through 11 land ports. New Delhi then introduced fresh restrictions on Bangladeshi exports, including garments, processed food, plastics, yarn, furniture and, more recently, raw jute and jute products.

Still, sea routes remain open for the businesses, but they are slower and cost more.

Humayun Rashid, chairman of Energypac Fashions Ltd, said his company sends $7 million worth of garments to India annually, mainly through land ports. Rerouting through Chattogram has pushed up transport costs by up to 20 percent.

He said Indian importers often complain about long lead times and rising transport charges. “So, my Indian importer met the Bangladeshi high commissioner in New Delhi for a solution through discussion. However, any meeting is yet to take place,” he said.

Despite the extra costs, Rashid told The Daily Star that his company’s trade volume with India has held steady.

Bangladeshi Commerce Secretary Mahbubur Rahman said he has written to his Indian counterpart three times seeking meetings to discuss rising non-tariff barriers and strained bilateral ties, but has received no response.

The commerce adviser also wrote to the Indian commerce minister requesting talks, Rahman told The Daily Star over the phone.

“The Indian side is also not saying why they are not interested in the meetings for removing the trade barriers,” he added. “Because of the non-tariff barriers, the cost of business operations rose by 20 percent.”

According to Rahman, no secretary-level meeting has been held between the two countries for one and a half years, although major trade issues are normally discussed at such forums each year.

Similar to Energypac Fashions, another local garment exporter, who asked not to be named, complained about the non-tariff measures.

He said disruptions at land ports had prompted his Indian partner to stop importing $2 million worth of garments from his company and instead source from Indian suppliers for its markets in Thailand and Malaysia.

Md Abdul Wahed, honorary joint secretary general of the India-Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce and Industry (IBCCI), said imports from India at some land ports have fallen by more than 50 percent in terms of volume since the retaliatory measures began in April.

“For instance, in some land ports, nearly 400 goods-laden trucks used to arrive from India in a day, but now the number has fallen to 150 a day,” he said.

“The trade relations between Bangladesh and India are not normal now, and the governments of both countries need to solve the trade barriers. In many cases of bilateral trade, the cost has risen to Tk 10 in place of the previous Tk 1.”

Before the latest non-tariff measures, long-standing non-tariff barriers had already hampered trade between the two neighbours.

The timeline of the latest retaliatory measures dates back to early April, when India revoked transshipment for Bangladesh export cargo to third countries via its land borders and ports.

In mid-April, Bangladesh suspended yarn imports from India through all land ports, including Benapole, Bhomra, Sonamasjid, Banglabandha and Burimari, though imports through Chattogram were allowed.

In May, India restricted the import of garments, agro-processed foods, furniture and other goods from Bangladesh through land ports.

India Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) said garments, the single largest Bangladeshi export to India, would only be allowed entry through Kolkata port and Mumbai’s Nhava Sheva port.

While Chattogram has so far absorbed much of the redirected flow, shipments to India through the 11 land ports as well as Mongla and Pangaon have fallen by nearly 15 percent in value and 19 percent in volume, according to official data.

Exports to India via Chattogram port rose 139 percent year-on-year in the first eight months of this year to $338.2 million, up from $141.4 million a year earlier, according to National Board of Revenue (NBR) data.