The news that New Hampshire is very close to 100% broadband penetration marks the culmination of decades of government and private investment to spread online connections throughout the state, work that goes back to the days of dial-up modems.

However, uncertainty about the Trump administration’s plans to hold back pre-approved funding means the next steps remain up in the air.

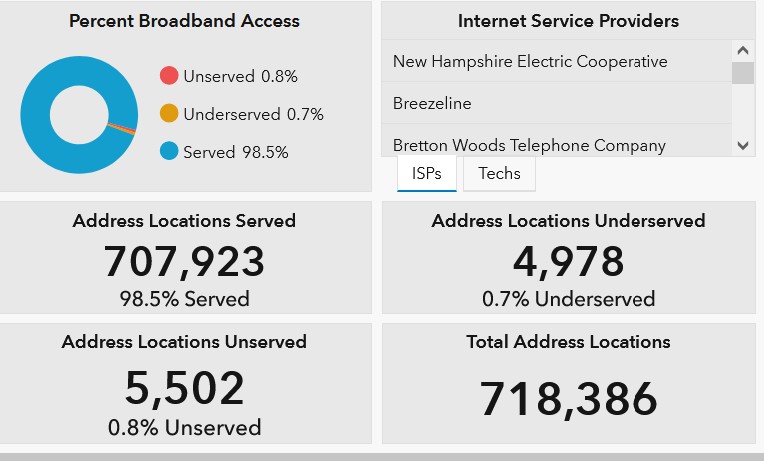

“In terms of FCC broadband maps, we only have about 5,000 addresses left,” said Matt Conserva, broadband program manager for the state Department of Business & Economic Affairs. More than 98% of homes and businesses in the state now have a broadband connection, usually fiber-optic cables, running close enough that they can be quickly hooked up when they wish.

The stragglers are mostly “long driveways, the last house on the cul-de-sac, that sort of place,” Conserva said. They include about 50 addresses in the town of Hill, the only town in the Concord area listed as having less than 97% broadband access on the state’s broadband map from the Division of Business and Economic Affairs.

Making the final connection to the Internet is usually a matter between the property owner and a private Internet Service Provider.

“From the telephone pole to the structure, we’ve found that the ISPs are covering that. Consolidated (Communications) covers 2,000 feet from pole to structure; (New Hampshire Electric Cooperative) is doing about 1,000 feet. Most of the time, there is no charge for installation,” said Conserva.

Satellite internet is also an option. New rules from the Trump administration included Starlink from SpaceX, a company founded by Elon Musk that provides satellite internet access from low-Earth orbit.

The information superhighway

New Hampshire has been working on spreading online access since the mid-1990s, when America Online CDs were the country’s biggest entry point to the internet.

Original efforts concentrating on building a “backbone” throughout the state, the big high-speed connections that are the data equivalent of the federal interstate highway system. Ironically, the spread of cell phones helped because cell towers needed hard-wired connections to the main internet, known as backhaul, and this often provided financial backing for the work.

The past few decades have seen a concentration on “middle mile” connections, the rough equivalent of two-lane state roads leading from the interstate to towns and developments. To complete the metaphor, that set of fiber and coaxial cable placed on poles makes it possible for individual buildings to construct their own driveway, giving them access to the entire network.

All this is expensive and although it can generate revenue and economic activity later on, government support has been needed to get it going, just as happened with the interstate highway system.

Uncertain spending after deployment

The recent build-out has been funded by money from what is known as BEAD, the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment fund, through the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA).

The state has been allocated $197 million in BEAD funding and has announced provisional awards of $19.4 million to bring access to the final addresses. That includes $6.6 million for Comcast Cable Communications, for fiber and hybrid lines to 573 locations; $6.2 million to Consolidated Communications, which has just rebranded as Fidium, for fiber to 2,574 locations; $5.6 million to New Hampshire Electric Co-Op for fiber to 884 locations; and $953,981 to Starlink to provide satellite internet to 1,105 locations.

After other costs that leaves “about $160 million” in what are called non-deployment awards to the state, said Conserva. This is money for broadband-related activities other than laying fiber and building nodes.

“Providing computers, training, cybersecurity — there are a whole bunch of things we’d love to use that money for,” he said.

State official created a digital equity plan to spend the funds under the BEAD standards as created under the Biden Administration, but in June, the Trump administration issued a policy notice through the National Telecommunications and Information Administration that said, among other things, non-deployment uses such as workforce development, digital literacy efforts or outreach could no longer be reimbursed.

“We created a digital equity plan but it has been taken back,” Conserva said.

New Hampshire, like other states, is in waiting to hear how much if any of that money will be available.

What to Read Next