Retired Ontario Justice Harry LaForme isn’t entirely comfortable with the label of “ally,” which many Jewish leaders have been using to describe him since Oct. 7. After all, LaForme—who was the first Indigenous Canadian to be appointed to the highest court in any province—says he always felt a kinship with the Jewish people, ever since his family told him his First Nations people were one of the lost tribes of Israel.

But over the last two years, the trailblazing lawyer and judge, 78, has become a frequently honoured guest in official Jewish spaces, earning thanks and praise for his outspoken condemnation of rising antisemitism here in Canada, and for his his support for Israel—which he calls the indigenous homeland of the Jewish people.

It’s a view that isn’t universal in Canada’s Indigenous community, and LaForme gets pushback for his stance. He’s aware of the perceived parallels between the First Nations’ centuries-long struggle to overcome the legacy of Canada’s colonial-settler past and the Palestinian battle for their own land and destiny. But LaForme says conflating the two issues is anathema to his religious beliefs about peaceful reconciliation. That’s why he’s come out in strong opposition to Canada’s recognition of the State of Palestine last week, the day before Rosh Hashanah.

On today’s episode of The CJN’s North Star podcast, host Ellin Bessner sits down with Justice LaForme to share his life journey, including a recent trip to Tel Aviv.

Related links

Read Justice Harry LaForme’s remarks in Tel Aviv at the Irwin Cotler Institute’s Democracy Forum in May 2025. Learn what Justice LaForme told the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights in May 2024 about antisemitism and Indigenous rights, together with Indigenous advocate Karen Restoule. A new book by York University professor David Kauffman about the ties between Canada’s Jewish and First Nations peoples, in The CJN.

Credits

Host and writer: Ellin Bessner (@ebessner)Production team: Zachary Kauffman (senior producer), Andrea Varsany (producer), Michael Fraiman (executive producer)Music: Bret Higgins

Support our show

TRANSCRIPT

Harry LaForme: But in Israel, I started off, and I got up and I said, I want to start this by recognizing that this is the land that Hashem promised to Abraham, and it’s the indigenous territory of the Jewish people.

Rabbi Aaron Flanzreich: It’s beautiful. Beautiful. (applause)

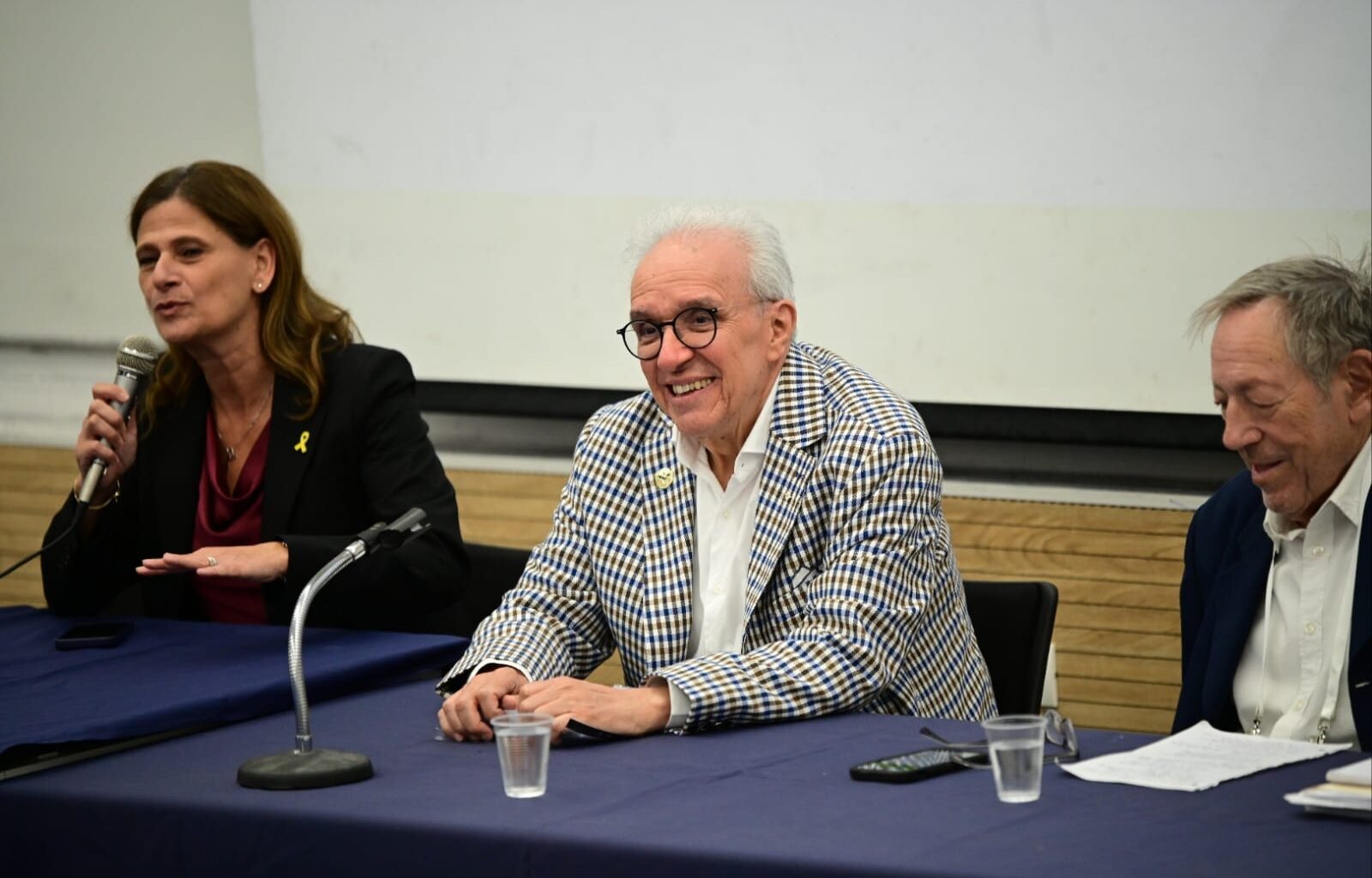

Ellin Bessner: That’s a snippet from a conversation on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, September 23rd, at Toronto’s Beth Sholom Synagogue, where the guest of honor, chatting with Rabbi Aaron Flanzreich, was a man who’s been dubbed an Anishinaabe Zionist or an Indigenous Zionist. He’s the Honourable Mr. Justice Harry LaForme, recently retired from Ontario’s highest court, the Court of Appeal, where over 20 years ago, he became the first Indigenous person in Canada appointed to such an important position.

It was Irwin Cotler who put him there while Cotler was justice minister in 2004. Justice LaForme has been spending a lot of time in Jewish spaces since October 7. He is honoured for his outspoken stand against antisemitism and his support for Canada’s Jewish community and also for Israel–although it’s a position that has earned him pushback from some people, including some in the First Nations community who identify with the Palestinians as being oppressed by settler colonialism.

But LaForme is not backing down. He speaks out about how he opposes the tactics of some people who’ve intertwined the Palestinian cause with the struggle of Canada’s First Nations to get their land back and control their destiny. Tactics he abhors have included hatred of Jews, isolation and othering of Jewish students on university campuses, and the hijacking of efforts to get clean drinking water for the remaining 37 First Nations reserves still without. by people wearing keffiyehs who chant that Jews should go back to Poland, advocate for kicking Jews out of Canada, and worse, out of Israel—a land that he believes was promised to Abraham and is the indigenous homeland of the Jewish people. The recent recognition by Canada of a Palestinian state just one day before the start of the Jewish New Year angers LaForme for many reasons, but mainly because he feels the federal government has been spending so much money and effort and made political statements about a conflict thousands of kilometres away, but hasn’t yet done right by Canada’s own nearly 2 million Indigenous people.

Harry LaForme: There’s over a hundred reserves that are still impacted by not having clean drinking water. I know Nishkandaga, for example, there’s a community that they have people on their reserve who have grown up and died and never had clean water come out of their taps. This is Canada. Where do I hear the indignation from Carney about that?

Ellin Bessner: I’m Ellin Bessner, and this is what Jewish Canada sounds like for Monday, September 29, 2025. Welcome to North Star, a podcast of the Canadian Jewish News, made possible thanks to the generous support of the Ira Gluskin and Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation.

Justice Harry LaForme’s life journey began 78 years ago in a mud floor house as a member of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation near Caledonia, Ontario. After spending his teen years trying to hide his identity to avoid racist bullying in school, it was coaching his little brother’s indigenous basketball team that turned him into a proud trailblazer for the rights of Canada’s Indigenous people. As a lawyer, then a trial judge, then to the Appeal Court, and along the way, enshrining human rights for other minorities too. He approved same-sex marriage in Ontario and medical marijuana. He sat as the original head of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission when it launched in 2008. Before the late Pope Francis came to Canada in 2023 to apologize for residential schools, LaForme had lobbied the Vatican to walk back its centuries-old doctrine that allowed white Catholics to enslave Canada’s first peoples. Now LaForme works as a senior lawyer at a Toronto law firm that specializes in Indigenous law, where there are also some Jewish colleagues, including the daughter of Canada’s outgoing Ambassador to the United Nations, Bob Rae. LaForme credits his love for Jewish people to his religious upbringing and many of the close friends he made with Jewish lawyers, especially later on the bench where they bonded over being outsiders. LaForme’s advocacy hasn’t just been confined to speaking to Jewish groups. He’s testified to Parliament about antisemitism, and he’s written op-eds in national newspapers. All this has earned him gratitude and accolades from many Jewish groups and led him to complete a lifelong desire recently and go to Israel. Justice LaForme joins me now from his home in Ancaster.

Harry LaForme: Oh, it’s my pleasure. Thank you very much.

Ellin Bessner: Well, it’s good to meet you face to face. We’ve spoken by phone, but I didn’t see, now I can see, that you have a yellow hostage pin on one lapel and the other lapel, of course, is your Order of Canada. Right? So maybe you could describe to us how you got the yellow pin and why you wear it?

Harry LaForme: Well, I wear it because, for the same reason that everybody else does. I want those hostages home yesterday. But the other thing, I don’t know where I got it because I’ve been to so many functions. I think it was at the Spirit of Hope gala last year, but I don’t know. I have a couple of them. My wife does the same thing. We also have the dog tags that I like to wear when I go to a Jewish function, or it doesn’t have to be Jewish, any function. They’re always a conversation piece. And you get to tell a little bit about why you wear them.

Ellin Bessner: You know, you have to wear the Order of Canada pin. It’s part of the thing, part of the deal, once you get it, I know that. You don’t have to wear the hostage dog tags or the yellow ribbon. And I know that you will have heard, and I’ve said this recently, that because of the threats that I personally have been exposed to by protesters and others, I don’t feel safe wearing my dog tags or my hostage pin or any Israeli pin anymore in public. And I feel badly about that. Do you get any uncomfortable reactions when people see that?

Harry LaForme: I don’t care. I mean, I take the attitude, look at. I’m 78 years old. I’ll be 79 next month. And I’m sort of like Bruce Springsteen. If you ever see a photo of him, he says he talks about his age, and he doesn’t give an F__ what he says or what people think of it, I’m sort of like that. I figure I’ve lived long enough that I have a right to my opinion.

Ellin Bessner: Well, you know, it’s wonderful to hear this. And I wonder, you know, when you hear Jewish people feeling that they have to hide their identity, it rings a bell for you in your childhood, growing up as an Indigenous person, maybe you would like to explain sort of the parallels of how you felt at one time you needed to blend in or hide.

Harry LaForme: Oh, I. I did. We were going to school in Buffalo, New York. That’s where my father had to go to get a job.

Ellin Bessner: He was an auto worker.

Harry LaForme: Yes. Yes, he was. So when we went to school, our first experience was really, really extreme racism. They came up to us. Kids came up to us. They stole our. Took our pencils and our rulers and everything and broke them and said we were, you know, these little savages and Indians. And so it became something that we tried to hide. And if somebody wanted to think I was Italian, I was good with that, or Greek or whatever, you know, I was —

good with that now. I had an experience when I was 19 years old. My little brother was a basketball player, and he said, because I used to play basketball in school, and he said, we need a coach, our coach won’t do our team. And it was an Indigenous basketball community. So I said I would coach. It literally changed virtually everything in my life. I spent a year with those kids and I was with a bunch of kids that wore who they were on their sleeve. They were so proud of who they were, they were so proud of their indigeneity, they were so proud of their communities and everything.

That kind of rubs off on you when you’re around it, and you see these young people with that kind of enthusiasm about who they are, you kind of do it. Shortly after that, I went to work with my association of Iroquois Allied Indians, which was a political movement in the early ’70s. I joined this organization, and interestingly enough, I worked in a residential school that was our office. They called it the Mush Hole, but it was the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario, and it is on Six Nations land. Anyways, it was an Anglican Church-run institution, and they had just closed it down as a residential school the year before. And the maintenance people were survivors of residential school—all of them.

One thing I learned from them, because we used to talk about it all the time, was the whole experience of residential schools and whatnot. What I was struck by was that they were not horrified by it, or they weren’t full of hate over it or anything like that. They used to talk about it, and there would be humour in their conversations, in their storytelling, and it was really something to behold. I found out later as I worked through this organization that that’s the way Indigenous people deal with trauma. But after a year, I decided I needed to go to law school because I thought all of these things are gonna be addressed someday by our courts. And I was right.

Ellin Bessner: You’re retired, but 31 years as a judge, 46 years as a lawyer. November 19, 2004, Irwin Cotler appoints you. The same announcement that they appointed the replacement for Rosalie Abella going to the Supreme Court of Canada. You get appointed. And you’ve mentioned many times how being “othered” at school helps you find common ground with other minorities who are othered You mentioned it was Greeks or Italians or, of course, the Jewish people that you encountered. When was the first time you remember meeting somebody Jewish growing up?

Harry LaForme: No, no, I met lots of Jewish people throughout my life. That’s why I have problems with the whole idea of being an ally to Jewish people, because it just seemed so natural. I’ve got so many friends and so many people that I absolutely love as friends that are Jewish that I never thought about it that way. I never thought about it as being an ally. I thought about just supporting my friends who I really loved, and I didn’t want anybody hurting them.

And that was the real reason. If the Jewish community wants to think of me as an ally, I’m okay with that. They can do that. But that’s not what I think of myself. I think of myself as a supporter of my friends and the people that I love. That’s what I think about.

Ellin Bessner: But it did take you to places where you probably never could have imagined, such as being honoured last year by the Canadian Friends of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre. You went to Israel in May. I mean, was that something that was even in your contemplation over the years ?

Harry Laforme: Oh yeah, I did contemplate that for many years. I always wanted to go to Israel, but you know, there were other things that kind of took over. I went to New Zealand, for example, in the ’80s. I’ve been to England several times. I really got a love-hate relationship with that place. Then I had this opportunity with Irwin Cotler again. He is a guy that I really, really had a lot of admiration for before the appointment. So it was a pretty big deal. When he appointed me, he knew that it was going to be the first Indigenous appointment. I told Irwin, I said, “I can’t figure out why me.” And he said, “Why not? Why you? It’s because who better to understand justice and what it is than somebody who has lived their entire life with injustice.” And I think about that all the time.

Ellin Bessner: You mentioned something just a moment ago I want to pick up on. You mentioned you have a love-hate relationship with the UK. So I want to bring up the fact that we’re talking just a few days after the UK, Canada, and France, and many other nations got together in the United Nations and recognized the state of Palestine. How do you feel about this?

Harry LaForme: Oh, I’m against it. I’m against it, and I’m almost embarrassed by it. There’s a lot of reasons. I’ll give you one. I think about how Canada, this Prime Minister, talks about the Gazans, the Palestinian people and everything like that, and all this indignation over how they’re treated and everything. I think about it and I say, “What about us as Indigenous people? Where’s your indignation about us and our history?”

Because from the very beginning, you have a constitutional provision in your constitution that says 9124, for example. It says the federal government is responsible for legislating in the matter of Indians and the lands reserved for the Indians. Now, you could have taken that any number of ways to interpret that, but they chose to take it and interpret it as master-servant, and it’s still in existence. It was the legality of residential schools, all of it. It’s got its basis in every piece of rotten history for Indigenous people in Canada that you can imagine. They don’t have any apologies about it. I never hear anything about it other than from a retired Prime Minister, Paul Martin, but other than that—which, by the way, was the one that appointed Irwin Cotler as the Minister of Justice—they surely didn’t change anything. We still have Section 9124 of the Constitution, we still have the Indian Act, we still have the magic of Papal Bulls and the Doctrine of Discovery that gave. It’s a figment of their imagination. It’s a piece of magic whereby they get to control all of the land that Indigenous people have.

Ellin Bessner: And let me just, for our listeners, we should explain in case they don’t remember, when the Pope Francis came and you met in Rome with him, but when the Pope Francis came to Canada and apologized for this Doctrine of Discovery which basically came back to like 1492, when white people and Christian people were the only ones who were allowed to colonize land, basically, in a nutshell.

Harry LaForme: Yeah, yeah. Back to the parallels of what Canadians and Canadian politicians and other Western politicians are dealing with.

Ellin Bessner: Back to the parallels of what Canadians and Canadian politicians and other Western politicians are dealing with. Wouldn’t it follow logically that if the Palestinians want their land back, their rights, their self-determination, you would sympathize with that? But I see you call the Israelis the indigenous people, so I’m trying to understand where that position comes from. Maybe you can help me.

Harry LaForme: Well, the position comes from my reading history, as I said at a conference when I was in Israel, I gave an address, and one of the first things I said was, “I want to acknowledge that we’re conducting this meeting on the land that was promised by HaShem to Abraham, and it’s the indigenous lands of the Jewish people, Israel.” So I said that, and I got a nice round of applause. That was good. So I care very much. That’s where that whole thing comes from. And I just read a book where it talked about the history of the Jewish people in the land of the old definition of what that land was, Palestine, which was given the name by the British. You know, that was the British. If there is anything about Israel that is false, it’s that they’re colonizers of the old Palestine, or what we call today Israel. They belong there. It’s probably, as my wife says, one of the most amazing examples of decolonization in the world. They’ve taken it back. They’ve taken back their original territory. And I agree with her.

Ellin Bessner: When we hear the narratives today, settler colonialism, and they use a lot of, and I’m talking about Canadian but also other Western nations. They use a lot of words like “from Turtle Island to Palestine”. The narrative is now intertwined with First Nation rights. How do you see that layered onto the Palestinian struggle? And are you troubled by it?

Harry LaForme: Yes, I’m very troubled by it because we, as Indigenous people of Turtle Island—that’s North America—our relationship was of peace and friendship with settlers. We had treaties and whatnot with these settlers which said, “we’re going to live here, you’re going to live there, you’re going to govern your people, we’re going to govern ours, we’re going to respect each other, and we’re going to do this, and we’re going to live side by side through this.” That existed for about 500 years until the late 1700s, early 1800s. That was how we lived. So whenever anybody asks me what my idea of reconciliation is, I tell them, and I guess that’s why I’m an Indigenous Zionist, or Anishinaabe Zionist, as I was called in the paper. I’m proud of that because I think it’s right.

Reconciliation to me is going back to those original relationships, which we know can work, because ours did for 500 years. And I say give us our land or some land, I don’t care if it’s that little spot of reserve that I have, and give me that land and give me the jurisdiction to rule that land and govern that land. And that’s real reconciliation. But nobody even talks about it, nobody even thinks about it. An example is Grassy Narrows. You want to talk about, you know, usurping what’s Indigenous and using it to support some kind of notion of indigeneity down in Palestine? Grassy Narrows has had a problem, like a serious problem for 50 years, and they’re still having it. And they keep promising and promising that they’re going to fix this, they’re going to fix this.

Ellin Bessner: And there’s some mercury in the water for our listeners who are unfamiliar. Right. And the poisoning of the water, yes. Last year it was sort of hijacked by pro-Palestinian teachers who forced kids to feel like they were settler colonials. While this was nothing to do with. But on the other hand, it seems to me that we have issues here in Canada that are very similar, for example, annexation of the West Bank, which some of the Israeli government political people have said they want to. How do you feel about that policy?

Harry LaForme: I don’t know. But far be it for me to suggest, when you have an enemy right at your doorstep who has got hundreds of miles of tunnels into your territory and has threatened to do nothing but, again and again, kill all Jews and remove Israel as a State. Then, on October 7th, they come along and they carry out the worst atrocity since the Holocaust, and Israel, in defence of themselves, says they have to do it this way. Who the hell am I to suggest to them that I know better how to defend Israel than they do? And I don’t try to get into their politics of Israel. I expect they’re at war with a terrorist group that wants to annihilate them. And far be it for me to suggest what is the right course of action for them to take. Just like it’s not Canada’s place to say, “You have to defend yourself this way, Israel, I’m sorry, but the way you’re doing it is wrong. Now you got to do it this way.” They wouldn’t listen if somebody told them to do it. And I don’t expect Israel to listen to them.

Ellin Bessner: Fair enough. Now you mention antisemitism? So we’ll bring it up again. Why is it anathema to you? How does it clash with the teaching, the seven tenets of your Creator, the seven characteristics?

Harry LaForme: I mean, all of our seven sacred teachings are all about respect and honour and truth. And that what they’re talking about, we wouldn’t, for example, occupy territory and prohibit a specific group from going there. Like that’s what happened on these campuses. You know, you can describe them any way you want, but I was there. I went to a couple of them, and I know what the circumstances were. They were denying Jews the opportunity to go into classes. They were denying Jews the right to be on that campus. That’s anathema to mw

Ellin Bessner: Or anyone who was a Zionist. Yeah.

Harry LaForme: Yes. So that’s what I say is wrong. It’s totally against it. And I didn’t. And when I get people coming out and looking at the cameras with a mask on and saying, “This is my land, this is my land. It was given to me by the Creator,” and everything like that, I want to just absolutely scream, because that’s not the way we did it. That’s not what our seven sacred teachings are about. And that’s not what we did for 500 years.

Ellin Bessner: Where would Caledonia or Oka fall into your approval or not approval of techniques and tactics in order to get recognition? Because to be fair, those are facts. Recent facts.

Harry LaForme: Yeah, well, I mean, they didn’t kill anybody. They’re not denying people the right to go anywhere. They’re not denied. They’re just saying, “You’re not going to build houses here.” Or, you know, you go to Oka, for example.

Ellin Bessner: Yeah, I covered it. I was there. (LaForme: So was I.) Yeah, I was there for CBC. And one person did die. But anyway, that’s, tes, that’s a long time ago. But, yeah, I mean, we don’t have to go into this history because I’m more interested in talking about how your journey has been, and we’re almost out of time.

Harry LaForme: So I want to say this. I believe in dialogue, I believe in talking about these things, and I believe in finding ways to find a solution to the problems and stuff like that. But every once in a while, when somebody doesn’t listen, like Canada won’t listen to the indigenous problems, they’re still not listening. Then you have to have an Oka. An Oka, I will say, wasn’t just made up.

Harry LaForme: It was because they were trying to take more land than they were entitled to, more Indigenous land, and turn it into a golf course or improve their golf course. It’s always about the land, always about the land and the traditions of indigenous people on that land. There’s a difference, I think. And for me, when that is usurped and people want to rely on that, then they better be right. Please just be right. And if you’re going to do it with Jews and Israel, then be right about your history. And if you’re not right, go look it up. Please educate yourself before you jump in and want to kill everybody.

You’d be surprised, I think, at the support that Jewish people have in Canada, by the rest of Canadians. I know the acts of antiSemitism are going up horrifically high.

But there is a big segment of Canadians that would support and do support Jewish people. They’re just too busy with their lives. I would say that about Indigenous people, too. I can’t speak for all Indigenous people in Canada, but I will say this: they’re so busy just living their lives week to week that they don’t really care about things that happen 16,000 miles, 12,000 miles away, you know, and they don’t care.

Here’s what I say about it. If people really, really understood the history of that region, the Middle East, and how many times the Jewish people for thousands of years have been expelled from that territory that HaShem did give to Abraham and promised him thousands of years ago, then they would know the real history. And if they know the real history, then I think they know the right position and they just don’t want to learn it. They want to learn it from a 30-second soundbite on TikTok.

And I can’t sit idly by and keep my mouth shut. And I won’t.

We have an extra bedroom in our house because a Jewish friend of ours’ daughter is going to Mohawk College or McMaster and she said she feels unsafe in certain circumstances or certain times, that she feels unsafe. We put this bedroom together, and we said, “You tell her that she’s got a safe place to go to anytime she wants.” And we have it, and it’s there sitting behind me empty, and it’s waiting for her if she ever needs it.

Ellin Bessner: It makes me sick to hear this, but I can’t imagine what goes through your feelings when you did this.

Harry LaForme: It hurts. I love this family, and I love this young lady, and the idea that somebody could make her feel unsafe or a place that makes her feel unsafe is absolutely soul-wrenching.

Ellin Bessner: We have shared trauma. Indigenous residential schools, Indigenous hatred, and Jewish Holocaust. Second generation, third generation, fourth generation. We have a lot in common, both of our communities.

Harry LaForme: You know, when I get invited to synagogues to speak, and I have been to quite a few, one of the things I like to do is take it as an opportunity to teach them a little bit about Indigenous history in Canada. And my purpose is to say I don’t expect the experiences are the same. They’re not the same, I know that. But they’re equally traumatizing and equally damaging.

I have a love-hate relationship with this country because I think it’s a grand country, but I think that its treatment of Indigenous people is painful to me. I can still cry over residential schools. I can still cry over the fact that they took our children away.

Our experiences are not the same, but our feelings are. Because I know that at the same time that people really like me and respect me and everything like that, they know I’m not the same as them. Canadians know I’m different. And that aloneness that you talked about is something that I lived with almost all my life. Every place I went, I was either the first. I don’t care whether it’s just going to law school with the first Indigenous students at Osgoode. And I was the only Indigenous judge that sat on a court of appeal for 14 years, alone. And the people that I identified with most there were my Jewish colleagues.

Ellin Bessner: And you know, I’ll tell our listeners that my grandfather was in your situation about 20 years earlier, more like 30 years earlier, the first Jewish judge to be appointed to any Supreme Court in Ontario and swearing on a Torah, not on a Bible.

Harry LaForme: And mine was on an Eagle Feather. But I did have some people to talk to, my Jewish colleagues, and they were the closest to me than any of my fellow judges ever were. My colleagues, the Jews, people like John Laskin, who I just absolutely love. Michael Moldaver, Steve Borins, Kathy Feldman, you know, the list goes on. And they were, they saved me. I’ll tell you, they saved me.

Ellin Bessner: Now you’re returning the favour.

Harry LaForme: I hope so. It doesn’t feel that way. I’m just helping friends.

Ellin Bessner: I want to thank you for sharing your time with The CJN, with our listeners here. To all of us.

Harry LaForme: Shanah Tovah

Ellin Bessner: Shana Tova to you and be well.

And that’s what Jewish Canada sounds like for this episode of North Star, made possible thanks to the Ira Gluskin and Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation.

Our interview with Justice LaForme was recorded a week before Canadians mark the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, on September 30, a day to reflect on the tragic legacy of the residential school system. The Ontario Court of Appeal, where Justice Laforme sat for 14 years, announced they will not hear any motions or appeals that day, and no counter service will be available either. If you would like to read more about Justice LaForme, go to the links in our show notes.

North Star is produced by Zachary Judah Kauffman and Andrea Varsany. Michael Fraiman is the executive producer, and our theme is by Bret Higgins. Thanks for listening.