The following excerpt is from Mastering Community Management: Chaos, Compassion, and Connections in Games by Victoria Tran. The book was published on July 17, 2025 by CRC Press a division of Taylor & Francis, a sister company of Game Developer and Informa Tech. Use our discount code BRAINROT25 at checkout on Routledge.com to receive a 20% discount on your purchase. Offer is valid through December 31, 2025.

Abstract

This chapter covers what a community is, how they form, and the culture around them as it currently stands. In particular, the rise of online communities and how they are the modern day gathering place, the role of avatars, and how our communication changes due to that. How this affects studios and real life will be explored, and overall is dedicated to giving shape and context to why online communities are so powerful and different than what we might think. It ends off on the author’s philosophy on the top community desire, which is to be seen, heard, and like they matter. Thus, this section will be the guidepost to driving strategy in a positive direction.

When I first joined Habbo Hotel, an online social game (A.K.A. chat rooms with avatars), it was pandemonium. Massive amounts of spam in the shared spaces, rampant not-safe-for-work rooms, and more. In particular, I was part of someone’s America’s Next Top Model community, where players would line up to have their outfits judged based on the theme, and the winner would gain access to the exclusive “friend group” and back area. Losers were kicked out of the room. It was fun, but most of all, the friendships I gained there felt real, and one older girl took me under her wing to guard me from creepy guys. I’d eagerly wait for school to end so I could go back to be part of what felt like an exclusive group.

I wasn’t a part of the Habbo Hotel community because I signed up for an account. No—I became a part of the community when I actually started using the platform, talking to people, and actively participating in what it had to offer me.

In the simplest terms: community is when a group of people have a shared sense of belonging that allows them to gather, engage, and connect with each other.

Community is more than just a group of people in a space. If it were simply that, anytime you opened the App Store on your iPhone, you’d be part of the “App Store community”. There is a difference between being in the same space as someone and feeling like you matter and encouraged to reach out to people. You don’t even need a platform to have a community either! Obviously communities have long existed before Facebook was invented. They have evolved in terms of where people go to find community. As we dive into building up communities, we must keep in mind these questions:

Who are the people we want participating in our space?

Where is the space they are gathering in?

What is the common language, slang, jargon, customs they will participate in?

Why are they there? The common interests, passions, motivations, or reasons for their time?

How will they share and learn from one another?

Community moves people. Community is what urges people into action. Community is what helps people grow, learn, and be exposed to a world outside of their own bubble. No matter where we are—online or offline—people crave a group of people like them. And the internet? It opens up a whole new level of exposure to people’s lives… and some new problems too. As community professionals we’re able to shape how these people connect and understand each other.

Communities are exactly the kind of thing developers are looking for in order to create better, more enjoyable game experiences. Metrics and data tracking will help quantify the most popular choices and issues in a game. A good community will work hand-in-hand with data to reveal even more: why something has occurred, the experiences and logic behind it, the emotions others may feel, and if this is something others would want.

Communities don’t just make sense culturally, but design and business-wise too.

How Communities Form

Bear with me as we dive into some solid sociology. How you tackle community management will start from the base assumptions you have of people and their interactions, and knowing your own base line will help you figure out what and why you decide to go a certain way, and if there is a different viewpoint that may help you gain perspective and understanding.

Culture and Community

Culture refers to the learned sets of meaning and behavior between members in a community. Interestingly, many people might not even be aware of their cultural nuances until they encounter a different one. Think of how a player might experience a cultural “shock” if they were to swap from playing multiplayer Stardew Valley to a competitive game of League of Legends. What is considered normal in one place might be entirely different in another.

Unlike a rigid method of living, culture can be considered more like a template that shapes people’s behavior. Almost like how a game can have a joint set of emotes players can pick from to add and remove as they wish. New members are able to pick up and learn the template, add their own spin to it, and the template can evolve overtime. These templates aren’t often followed in their entirety, but they give many people a starting point to learn how to interact in ways that both enhance bonds and minimize misunderstandings. It’s powerful!

Religion, marriage, and even memes are a form of culture. Culture change often moves MUCH faster than laws can (e.g. internet culture has evolved at a much faster pace than any entertainment or media law can keep up with), but sometimes law can move or define the culture (for instance, the death penalty.) And the communities we create inevitably have their own type of subculture within the larger “culture” of the gaming community.

This act of actually influencing and shaping behavior is called socialization. This is a life-long, active process—it can change overtime, and takes time to form as we. Children in particular soak this up quickly, but also will try to negotiate and limit test to see where the boundaries are. With each “failure” they have (e.g. every time they get in trouble for acting a certain way), they learn what behaviors are okay. (You may find that adults in your community will limit test too. But they’re not children. They’re just annoying. Heh. I’m joking. Kinda.)

We’re able to shape not just communities, but literally the culture someone is in. I don’t say this to inflate us into some life changing entity, but we do have a large influence on how the spaces we work in progress and interact with each other. And the culture players are in is important, beyond just having someone to talk to! It also influences the kinds of people they’re exposed to, their resources, and even their attitudes and biases.

The Rise of Online Communities

So, fun fact, the internet is pretty popular nowadays. (This is the kind of groundbreaking insight you’re reading this book for, I know.) Especially when it comes to our games, whether AAA or indie, we rely on having a healthy community to give us feedback and sustain our studios.

There are three main areas in which your community may form as it relates to games:

Social networks. While social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and other services are generally not necessarily conducive to back and forth conversation between players, there’s no denying it’s an important part of how gamers interact and find each other, so would feel wrong not to dive into the most culturally relevant platform.

Forums. I include instant chat services like Discord in this. Reddit, Steam forums, or your own hosted forums on a website. While not as prolific as before, these are one of the places some of your most hardcore fans will be.

In-Game. While this book will focus less on the actual in-game design of spaces (as those primarily lie with the game designer), the in-game community is inextricably linked to the community that gathers outside of it, so it’s important to take note of how they influence each other.

It doesn’t matter where you start out, so long as the players can find you. As your community gets bigger, it’s likely they will branch off and create communities not directly tied to you. This is good! It’s a sign of a successful game when you aren’t able to control every aspect of it.

While we have fallen into a slight trap of the internet needing to be “entertaining” to be worthy—this is not the way we should be tackling it. As community builders, we can make the internet more than just entertainment. It is belonging, growth, and learning.

Third Spaces

I like to think of online communities working very similarly to real life cities or neighborhoods. A city is a conglomeration of people from all walks of life—different cultures, beliefs, socioeconomic backgrounds, and so on. Even in monocultural countries, there are still differences between people and their understandings of the world, plus tourists, in many cases. A well planned city has multiple places in which people can gather together—parks, libraries, public recreational areas, community centers, block parties, etc. There is lots of care and consideration for how people find each other in cities that aren’t necessarily profit driven. Online communities need that same amount of care and consideration—structuring and designing the space for it to survive in the long term, whether that’s for a business or not.

These places where people gather in cities can be described by a term coined by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg: “third spaces”. These places refer to spots that someone goes to that are not their usual social environments of the home and the workplace. (And now with remote work, sometimes there isn’t even a “second” place.) Third places can be things like parks, a cafe you frequent, public libraries, gyms, bars, churches, community centers, a comic book store, etc. Oldenburg argues these third places are incredible important for society, engagement, and feeling like you truly belong in a place.

And with the prevalence of the internet, many people are starting to find an almost “fourth” place there. Or perhaps, in some scenarios, the internet IS someone’s third places due to a lack of accessible real life third places (distance, a global pandemic, etc.)

Thinking about digital communication through the lens of the spaces we build is important because it encourages us to consider how that design and structure can shape relationships, rather than just using it to advertise products or exchange information. A community requires not only common goals or interests, but a sense of interactivity and understanding between each other.

If we look at what a third space needs to be considered one, we can see that the internet actually can contain a lot of similar characteristics:

Neutral ground: There is no obligation to be in the space and you are free to leave and come back whenever you want.

Leveler: Your socioeconomic status, unless in a game that has pay-to-win tendencies, is not apparent nor overly important.

Conversation is main activity: Light-hearted and good-natured conversation is the main focus of the space, though not the only activity.

Accessibility & accommodation: Must be accessible and provide for those the enter the space.

Regulars: A number of regular people that visit the space that set the mood, tone, and characteristics. Often they help newcomers feel welcome.

A low profile: Not pretentious, accepting of people that come to it no matter their background.

Playful mood: Being playful and good natured is common and highly valued.

Home away from home: A feeling of belongingness and regeneration by spending time there.

This is, of course, assuming all goes well and no laws are being broken. But if we take these characteristics and apply them to game communities, we can see many of our characteristics or at least goals aligning.

A well functioning community relies on collective efficacy, which is a group’s ability to trust each other and work together. There are shared expectations on behalf of the common good of the space (e.g. not throwing trash into your neighbor’s lawn.)

The cool thing here is you don’t need strong social connections for collective efficacy to occur. You don’t have to like every single one of the people in your city to be able to make something happen, just a mutual sense of understanding and trust. And having this makes living or interacting in space that much more pleasant.

A mutual sense of trust is maintained by:

A willingness to help others out.

Taking actions to gain understanding.

So in our roles, we want to encourage and create this sense of mutual working trust not only between players, but between the developers and players.

And to combat any naysayers about internet communities being inherently “bad” – what does that mean? Before you can assign a judgment like that, we need to be clear about what the role and function of an online community is supposed to be.

This isn’t to say online spaces can replace (or should replace) real life third spaces. However, they’re an almost inevitable part of life, especially as the years go on. We still need strong resources, third spaces, and offline interactions, but there’s no denying a huge chunk of time for younger folks (wow I feel old) has been replaced by time spent on social media, or in our case, in games.

Because of this, we can’t just ignore online communities or treat them with blanket templates or rules. Community managers are the designers and maintainers. What are we doing then?

Avatars, Personas, Anonymity

A special part of online communities in particular is the persona people can create—whether in game or on social platforms. Whether it’s a highly curated version of themselves, a completely new version, or even an anonymous entity, there are endless options for people to be what they want to be.

As social media has become more prolific and being an influencer as a career choice becomes more interesting to folks, you may also see a rebound effect where folks begin to overshare. Daily vlogs, relatable content, personal life confessions, even babies can be dragged into it before they’ve even begun to understand what consent is if parents begin to do it. We’ve evolved past the time where it’s weird to be friends with internet strangers. Arguably, it’s even expected and professional in games.

Even more than other industries, part of the fun of games is to adopt some sort of persona online. Game communities are great at being a leveler in that sense. Through avatars, profile pictures, and text chat, social identification is dependent on those chosen aspects rather than judging the actual face of the person behind it, or even the voice. (This is separate from badges or follower counts one may have, but at the onset, everyone starts from 0.) This isn’t to say that people don’t go by their real name or photos, but that a large part of gaming culture is the ability to embody the character or avatar you want to be. It’s common to refer to someone as only their online name—knowing them as an alias rather than their legal given name. To know their character more than they know your face. This creation of social identity—masking the background or visual cues (and sometimes things like accents) add to the interesting dynamic of social interactions in games, where the playing field seems “level” and it’s assumed at first glance, everyone is coming from a similar background and history as you.

While it’s great this happens, it also creates a higher chance of culture clash with the high levels of interactivity with low context.

Communication Changes

As communication channels evolve with the help of reaction GIFs, emotes, emojis, and memes, this creates further incentive for folks to chat with each other in a shared language. This is particularly helpful for people who may have struggled in real world communication.

However, while removing face-to-face interactions means the nuances of expressions are gone (for better or for worse), it’s replaced by written nuances. Is typing in proper punctuation in a casual conversation seen as someone being tense or stoic? Is typing in all caps angry yelling or just fun excitement? What happens when voice chat is added to the mix, but again with no facial cues?

These changes in communication styles are things we need to constantly keep in mind as online communities develop and attempt to understand each other.

Studios and Communities

I can rant and rave about how wonderful and culturally significant communities are, but at the same time, I know what you’re here for. Community management falls under a larger marketing umbrella, and especially with independent studios, you often have the role of handling numerous aspects of social, marketing, public relations, and even sales.

So, while we will be tackling the values and ethics of communities, we can also acknowledge that while living in a capitalist society, there is a business value to maintaining communities too. While the two may seem to clash with each other, there are ways in which they find a happy medium that we must find. After all—we need to survive as community managers and studios too! We have games to make!

For many, the actual business value of a community is hard to calculate. The value will be determined by the key players in your studio, here is a small example of what communities can do for a studio. (We will dive into actual tracking further on in the book, don’t worry!)

Loyal fan bases for repeat customers

Word of mouth marketing (the best!)

Helping new players understand how to play a game/leading them

Lightening direct lift of onboarding and teaching

In games, it’s wild to think we are willing to sit down for things like Nintendo Directs, E3 (RIP), and other similar showcases. While new game releases and updates are very cool, it all technically is just an advertisement.

Movies do have something similar, where you watch trailers if you are early enough to a movie premiere. But the closest thing you get to people wanting to willingly watch ads at such a hyper focused scale is something like an Apple presentation.

But this is why a community is so important. All these events have some sort of community surrounding them, willing to do something like watch 3 hours of advertisements but also willing to tell their friends about it. There is a level of identity and excitement. You can always copy the infrastructure of a community but you cannot copy the identity, relationships, and emotional depth of one. Your community is your own, and that’s what makes it valuable and so hard to cultivate. You can’t copy it!

Your community is willing to sit down and get excited with you. It’s an incredible power to be able to move people, particularly into action, which is why when we build and maintain our communities, we need to ensure we’re doing it right by them, the industry, and ourselves. This is where designing communities for kindness comes in.

Real Life Still Affects Life Online

One of the things we need to acknowledge before we get into our own design of communities and kindness are the limitations we work in.

Communities are not a substitute for individual growth or real life interactions and everyday living. While online spaces can be many things—a reprieve, a place for growth and learning, a place of solace—it is not a replacement. It is an enhancement of one’s own lived experiences and communities, expanding it and providing context that may have never come to be before. It can encourage actions and growth, but we are not beings that can detach our regular lives from our online spaces. The internet cannot completely rip away the importance of real life interactions and circumstances.

It’d be wrong to talk about community building without considering—gasp—capitalism. The fact we work in spaces that need to profit does change our interactions with it. And there’s nothing wrong with acknowledging that—in fact, we HAVE to. We need to understand what the boundaries are if we are to ethically engage with our communities in a way that is beneficial to both the people and the studio.

For instance—class and income levels can drastically affect who spends time online. According to a study by the PEW Research Center in 2015, teens who are from more affluent households are more likely than those from lower-income households to say they hang out with friends in person outside of school. Lower-income teens are also less likely to play online games with in-person friends as opposed to their more affluent peers.

So, as we create communities online, we need to account for and consider situations in which we are inadvertently making biased assumptions in both structure and management of them. For instance, when we create communities, are we considering how some of the most vulnerable groups are being onboarded and welcomed into the space? For example, we can account for:

This is not to say we need to give up entirely or even that it’s a huge undertaking to consider these things. Merely that as you continue reading this book, keep in mind what kind of biases you may hold about a player (e.g. “ugh why are they using such an old rig to play this game and complaining) and consider how we can approach situations with the nuance they often deserve.

How are Game Communities Different?

Game communities aren’t like other B2C communities. (Cue the “I’m not like other girls” joke here.) The audience will be influenced by a number of factors, including: studio culture/voice, game genre(s), game tone, and number of players. From this, you can judge where your primary community demographic will come from, and how you can design appropriately.

With games, we are closely tied to our players. This is also because games are such an intense bonding experience—you physically feel like you are in the game, taking on the character, experiencing the stories. So! The communities we create and what they bond over will be influenced by the structure and rules, but also the kinds of games the studio makes. They will attract certain kinds of people seeing a certain kind of experience. That being said, this doesn’t mean your horror shooter game cannot find a positive, warm audience. Merely that your structure may have to account for a different mindset going straight in.

Examples of the type of community ethos a certain game may attract:

Mastery: Comprehensive knowledge or skill in a subject or accomplishment. Example games: Dwarf Fortress, Darkest Dungeon, Cuphead, Monster Hunter

Competitiveness: Having a strong desire to be more successful than others. Example games: Rocket League, League of Legends, Fortnite

Kindness: friendliness, coziness, generosity, trust, or inclusion dynamics. Example games: A Short Hike, Tiny Glade, Animal Crossing, Slime Rancher

Of course, these are not exhaustive or exclusive. Communities can be and usually are a mixture of many people, personalities, and game genre interests. But by knowing what type of community ethos you’re aiming for, you can appropriately plan for things such as:

Types of social platforms needed/their structure.

Amount of moderation needed.

What sorts of risks come with each community.

Accessibility to Creators

There is a certain level of fanaticism games get, but also, a certain level of accessibility unlike other entertainment genres. When people get hyped over a movie, they can’t just join Christopher Nolan’s official Discord server to talk to the production team about Batman. They aren’t attending a game convention and hanging with the developers.

Self-Motivated Space Creation

Game communities are incredibly organic. Even more than other industries, it is natural to create a game community of some sort, even if it’s just with your friends to get a good raid in together or form a guild. It has inherently been built into gaming culture from the get-go. With this kind of space creation for each other, we are actually frontrunners in terms of what many other industries wished their consumers did. But with this, we also tend to fall into the trap of taking these places for granted and not trying to build on them and improve them.

Conflict is Key

Conflict or friction tends to be part of the core experience of a game! How do we work with this? Usually people would avoid this, but in games, we WANT conflict sometimes. We encourage it! Me VS you! So we need to ensure we are keeping the spirit of the game, while also encourage sportsmanship among our players.

Comfortable Conversation Starters (And Sometimes, Passionate Ones)

Playing games with others are especially helpful because they tend to bypass a certain awkwardness of real life conversations, and the struggle to find a common interest. After all, whether you’re new to games or not, the fact is you’re all playing and experiencing this one game. And better yet, things happen in games, and they’re often exciting, emotional, or surprising. This generates a huge opportunity for conversation starters and can even be great segues into deeper ones. Especially if you want to play with this person again, asking them or adding them as a friend online is entirely normal, and often done through a process that doesn’t feel as personal as, say, giving someone your Instagram account.

Taking these things into account, we’ll be structuring our community strategy to either encourage or manage expectations when it comes to these activities, and ultimately aim to use this to sustain the interest and longevity of our spaces.

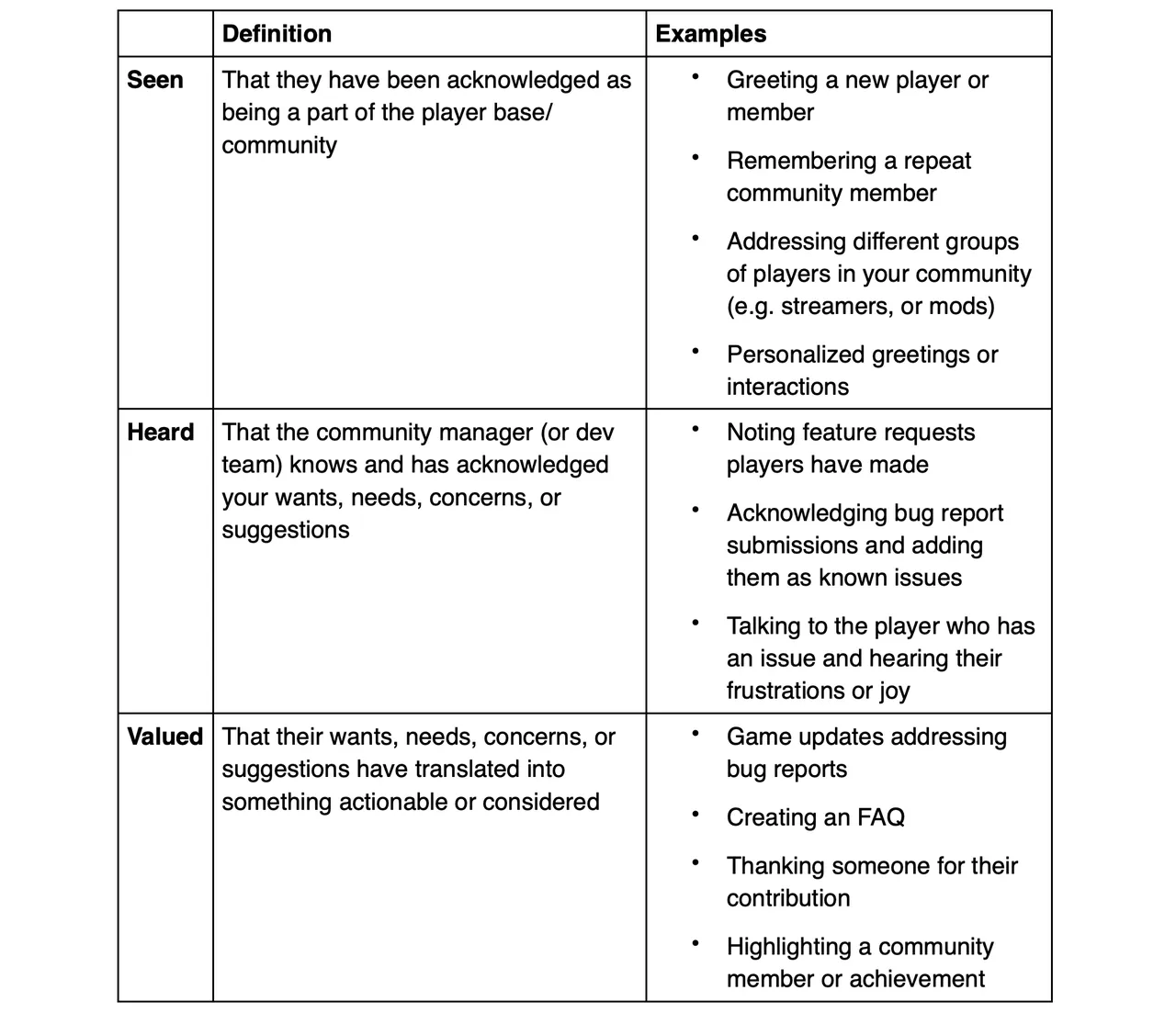

My main philosophy when it comes to dealing with anyone—players, coworkers, strangers—is that they want to feel seen, heard, and valued. I use these 3 points to always direct how I do community management and everything it touches, from social media strategy to writing a dev log.

As we dive specifically into game communities, here are some ideas to help drive your strategy in a positive direction:

Interactions matter. At some point, your community should not be built around your posts. It should be built in the replies—to you and to each other. Community is not a one way street.

Activity matters—in all ways. While a community that talks and engages with each other is important, do not forget that lurkers and those that more passively consume content are just as important to the community. Most people do not interact in a space—that’s normal. But while we do want to encourage activity, know that some silence is normal.

Louder does not equal right. While you may have more opinionated, angrier, or passionate members, remember their thoughts do not drive the direction of everything you do. They should certainly be taken into account, but part of your job is to figure out what is noise versus what is worth paying attention to.

Small moments matter. Paying attention to the details of a relationship will do wonders. If your partner hints that they love flowers, occasionally surprising them with small flowers and remembering their favorite treat will do more for you than a single grand gesture on Valentine’s Day. (Okay this isn’t a dating advice book, so I could be wrong, but also… I’m not. Shush.) Pay attention to the hints your community drops for what they appreciate. What parts of the game do they gravitate towards? Do you remember a mod’s birthday? Do you take the time to check in on folks?

Be agile. Community moves just as fast as technology. New social platforms, new problems, new ways to connect. Ensure you’re keeping on top of the trends and don’t be resistant to change and experimentation.

A community needs kindness, resiliency, connection, and sustainability. We’ll dive more into this further on in the book, but these will ensure your community doesn’t just survive, but thrive.

As you continue reading on in this book, I hope you keep that exact philosophy in mind for your own activities! After all, this book is NOT here to tell you exactly how you should structure or run your communities. To treat communities as a generality is a disservice to their complex nature. Instead, this book aims to provide you with resources, suggestions, and ways in which you can understand how to best work with your communities no matter what size it is.

References

Oldenburg, Ray. 1999. Great Good Place. Marlowe & Company.

Lenhart, Amanda. 2015. Pew Research. August 6. Accessed 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/08/06/chapter-3-video-games-are-key-elements-in-friendships-for-many-boys/.