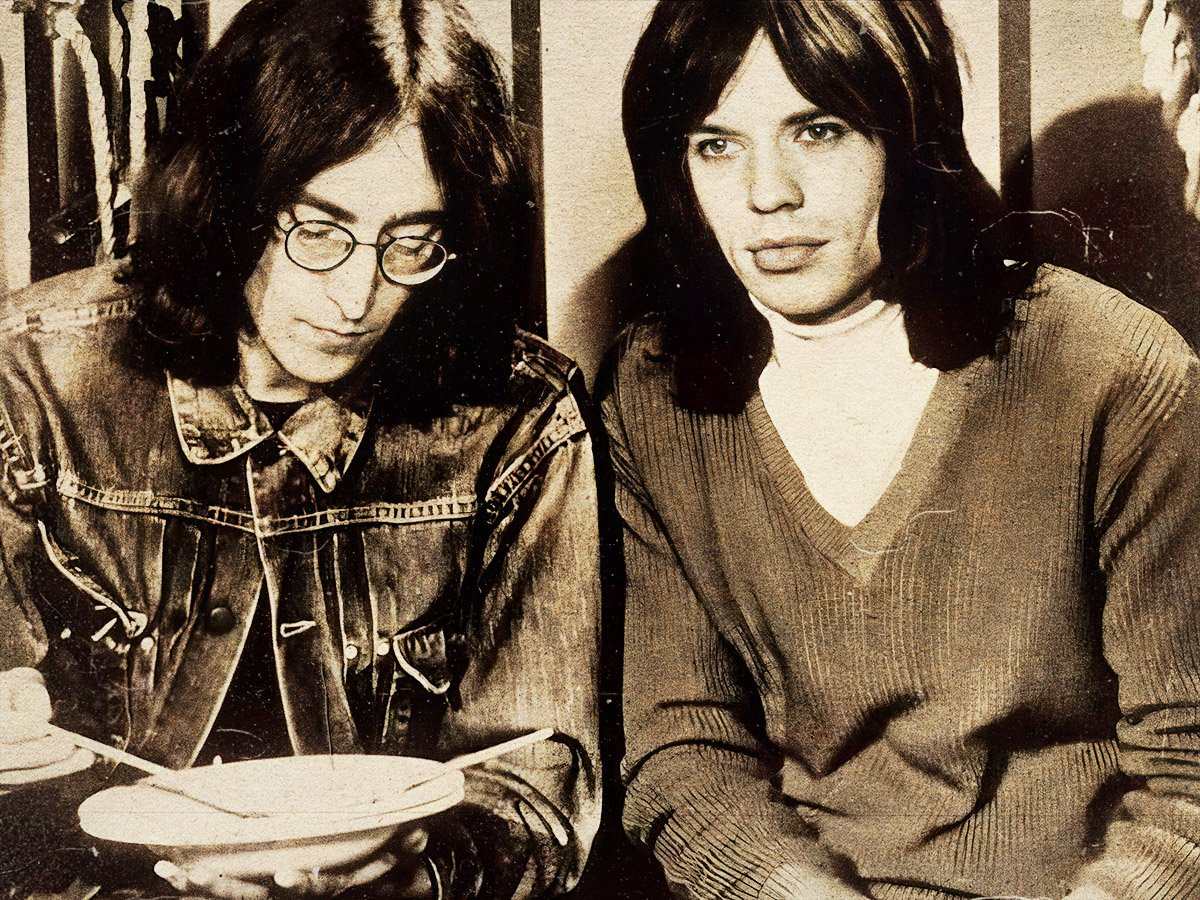

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Mon 13 October 2025 14:00, UK

Behold the mystery of John Lennon: purveyor of peace, love, and drunken disorder, an avant-garde radical with a keen eye on the charts, a bespectacled puzzle who only gets more enigmatic over four decades on from his death.

There are many great ironies to the man, but one notable example is that he quite rightly decreed that The Beatles were “more popular” than Jesus at one point, but also worried about his star waning thereafter. It seemed self-evident that he was in the history books as a pop culture hero to the world, but to Lennon, his position was always perilous.

You might imagine that he wouldn’t care about such trappings, but when Elliot Mintz became his friend in the 1970s, he recalled the Liverpudlian flying off the handle about what he saw as The Rolling Stones taking an undeserved lead over the Fab Four in the league of critical praise.

“He felt the Rolling Stones got the kind of adulation and respect that ‘The Mop Tops’ didn’t, and that the Stones were perceived as the revolutionaries because they came forward with ‘Street Fighting Man’ as opposed to ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’,” Mintz told Spin.

He was pained by this perceived softness on his part, particularly considering Ian Anderson claimed, “Lennon was probably the only one who’d be handy in a fight… Mick Jagger always looked too self-conscious to be considered a tough guy; he looked like he’d fall over if you blew on him.”

Despite friendly relations with the band, Lennon privately railed against the narrative that the inverse was true, as Mintz adds, “He loved Mick Jagger, and the two of them spent countless nights together in London. But when he would get really angry about it, he’d called them ‘the Rolling Pebbles.’”

Ironically, it was around this time, the truth was that the critics were claiming that the Stones had taken things too far. After the tragedy of Altamont, many fans and magazines had turned against the group, seeing them as a misstep away from the 1960s idealism that the very same ‘Mop Tops’ helped to define.

In truth, psychologically, it seems that Lennon had to invent imagined yardsticks to serve as artistic motivation. As Mintz explained, “He had that same kind of envy of the way people perceived Bob Dylan,” he continues. “He insisted to me he was a far better writer than Dylan was. It was a love-hate thing.”

In essence, he had to write music with a point to prove. If you’re already hailed as an unimpeachable pinnacle, then what’s the point? Who writes the better song: the scorned and underappreciated artist hoping to dethrone his idols, or the man who has everything, wondering what’s left?

Related Topics