The term “emerging artist” likely conjures up an image of a struggling twenty-something splattering paint on to an experimental installation that no one would ever buy. Today, while experimentation is still welcomed, the art world’s definition of what constitutes an emerging artist has broadened to encompass practitioners outside of the mainstream, of any age — and the desire is definitely to sell.

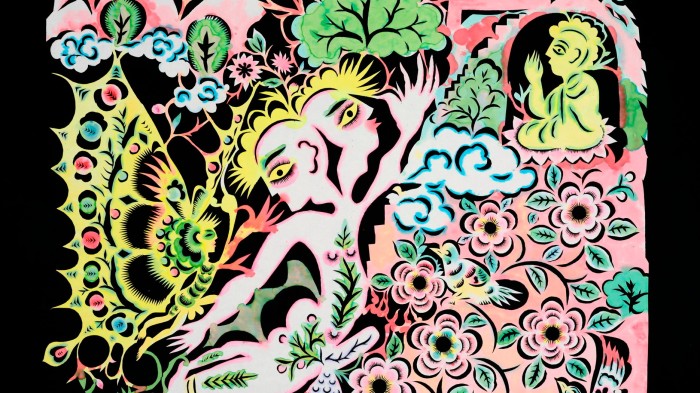

The shift is evident at this year’s Art Basel Paris, where 15 artists comprise its “Emergence” section, and are by no means all straight out of art school. The oldest on show is Xiyadie, a self-taught, Chinese papercut artist in his early sixties, who explores homoerotic themes through delicate works. His gallerist, Mimi Chun of Blindspot Gallery, says “I’m quite impressed by the fair organisers. I think [including Xiyadie] is a statement about supporting and being open-minded to artists from a diversity of practices and backgrounds.”

Chinese papercut artist Xiyadie is being shown by Blindspot Gallery © Courtesy the artist

Chinese papercut artist Xiyadie is being shown by Blindspot Gallery © Courtesy the artist

Xiyadie has had international recognition, including recent showings at the Venice Biennale and The Drawing Center in New York. But, Chun says, “until he was in his forties, he identified as a migrant, blue-collar farmer, not as an artist”, noting that he didn’t have a commercial gallery until 2018. Much of this stems from being a gay man in rural China, where he grew up before moving to Beijing — his name is a pseudonym, meaning Siberian Butterfly, which he used to protect his identity in the city’s subcultural scene, Chun says. The works she brings to Paris “tell the story of coming out, part biography and part fantasy” and comprise unseen, historical papercuts from the 1980s and ’90s, as well as four new and larger pieces, in bucolic settings, revealing a later-life “utopian vision of people coexisting in harmony with nature,” Chun says.

‘Ricochet: CBTT II’ (2025) by Kandis Williams © Stefan Korte, courtesy of the artist and Heidi, Berlin

‘Ricochet: CBTT II’ (2025) by Kandis Williams © Stefan Korte, courtesy of the artist and Heidi, Berlin  ‘Ricochet: CBTT I’ (2025) by Kandis Williams © Stefan Korte, courtesy of the artist and Heidi, Berlin

‘Ricochet: CBTT I’ (2025) by Kandis Williams © Stefan Korte, courtesy of the artist and Heidi, Berlin

Pauline Seguin, founder of Berlin’s Heidi gallery, brings a film, collages and lenticular prints (which shift according to viewpoints) by the research-based American artist Kandis Williams (born 1985). Seguin describes the works, which explore racial dynamics in the context of US militarisation, as “visually strong, and will also challenge fairgoers”. She finds that the word “emerging” gives artists some license to grow and experiment “with a freedom that established artists don’t have any more”.

Clément Delépine, the outgoing director of Art Basel Paris, says the same is true of the galleries in this section. “If you look at the exhibitors for an [emerging] art fair like Liste in the 1990s you had participants such as [the now well-known] David Zwirner, Galerie Eva Presenhuber and neugerriemschneider. Some of the galleries you now see in Emergence could become powerhouses in the next 20 years.”

Iran-born, Berlin-based artist and filmmaker Arash Nassiri © Chloe-Bonnie More

Iran-born, Berlin-based artist and filmmaker Arash Nassiri © Chloe-Bonnie More

A theme that runs through many of its artists is that, like Xiyadie and Williams, they have had museum and other institutional recognition but are only just making their mark on the international, commercial scene. London’s Ginny on Frederick gallery is bringing an installation by Iran-born artist Arash Nassiri (b1986) that addresses issues of urban displacement through dolls-house sculptures of empty Tehran shops with flickering neon signs in Farsi. Nassiri has recently shown at the respected KW Institute for Contemporary art in Berlin and has a forthcoming commission for London’s Chisenhale Gallery and the Fondation d’entreprise Pernod Ricard in Paris. His new sculptural installation for the Paris fair is, says gallery founder Freddie Powell, “a work that needs a lot of eyes on it”, something that Art Basel, and the very visible first-floor balcony position of its Emergence section in the Grand Palais, can provide.

Of the “emerging” definition for artists, Powell says “hopefully we can strive for a more inclusive meaning, which is more about the moment for any particular artist, rather than referring to an art-school graduation date”.

‘Farming’ (2025) by Xiyadie, at the Blindspot Gallery booth © Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery

‘Farming’ (2025) by Xiyadie, at the Blindspot Gallery booth © Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery

It all comes at a time when the wider art market is turning its taste towards lower-priced art, for which “emerging” normally fits the bill. Nearly all of the Emergence galleries interviewed by the Financial Times have booths priced below $60,000. Xiyadie’s work, which starts at $4,000 and tops at $30,000, is “well priced” for the current climate, Chun says.

The powerhouse galleries are responding to the latest demand and increasingly proposing co-representation arrangements with their smaller peers to secure the latest crop of artists. At Art Basel Paris, Hauser & Wirth’s booth will include their recently shared, earlier career artists, the haunting painter George Rouy and collagist María Berrío.

‘The Plot’ (2025) by María Berrío © María Berrío; courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Victoria Miro; Photo: Bruce M White

‘The Plot’ (2025) by María Berrío © María Berrío; courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Victoria Miro; Photo: Bruce M White

When it works, in collaboration rather than competition, their younger gallery counterparts cautiously welcome the dynamic. “It is a reality that is on the up. But it’s good that there are more big galleries contacting me, rather than going directly to the artists,” says Alex Vardaxoglou, who brings a vast new work by Tanoa Sasraku (b1995) to Emergence. Powell finds “you can learn a lot from bigger organisations. It can open doors, but [if not collaborative] it can also close them.”

Detail from ‘Mascot’ (2025) by multimedia artist Tanoa Sasraku, at the Vardaxoglou Gallery’s booth © Photograph: Jack Elliot Edwards; courtesy the artist and Vardaxoglou Gallery, London

Detail from ‘Mascot’ (2025) by multimedia artist Tanoa Sasraku, at the Vardaxoglou Gallery’s booth © Photograph: Jack Elliot Edwards; courtesy the artist and Vardaxoglou Gallery, London

Whether or not the traditionally conservative French collector base is equally persuaded by the latest up-and-comers remains to be seen. Seguin says that “France has this beautiful tradition of appreciation for the arts in general, though not so much for the cutting-edge. I will be very interested to see how they will react to [Kandis Williams’s] work.”

Delépine concedes that “Paris was perceived as more dusty, and with longer validation cycles [for new artists] than London or New York.” Now though, he says, his fair’s Emergence section coincides with “an interesting generation of artists coming of age, many of whom were foreigners who have made Paris their home. There is a new dynamism to the city.”

October 24-26, artbasel.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning