An autonomous art form

Rooted in rich crafts and traditions that studios comprehensively carry out in collaboration with the art and design world, the work of the printmaker goes largely unseen.

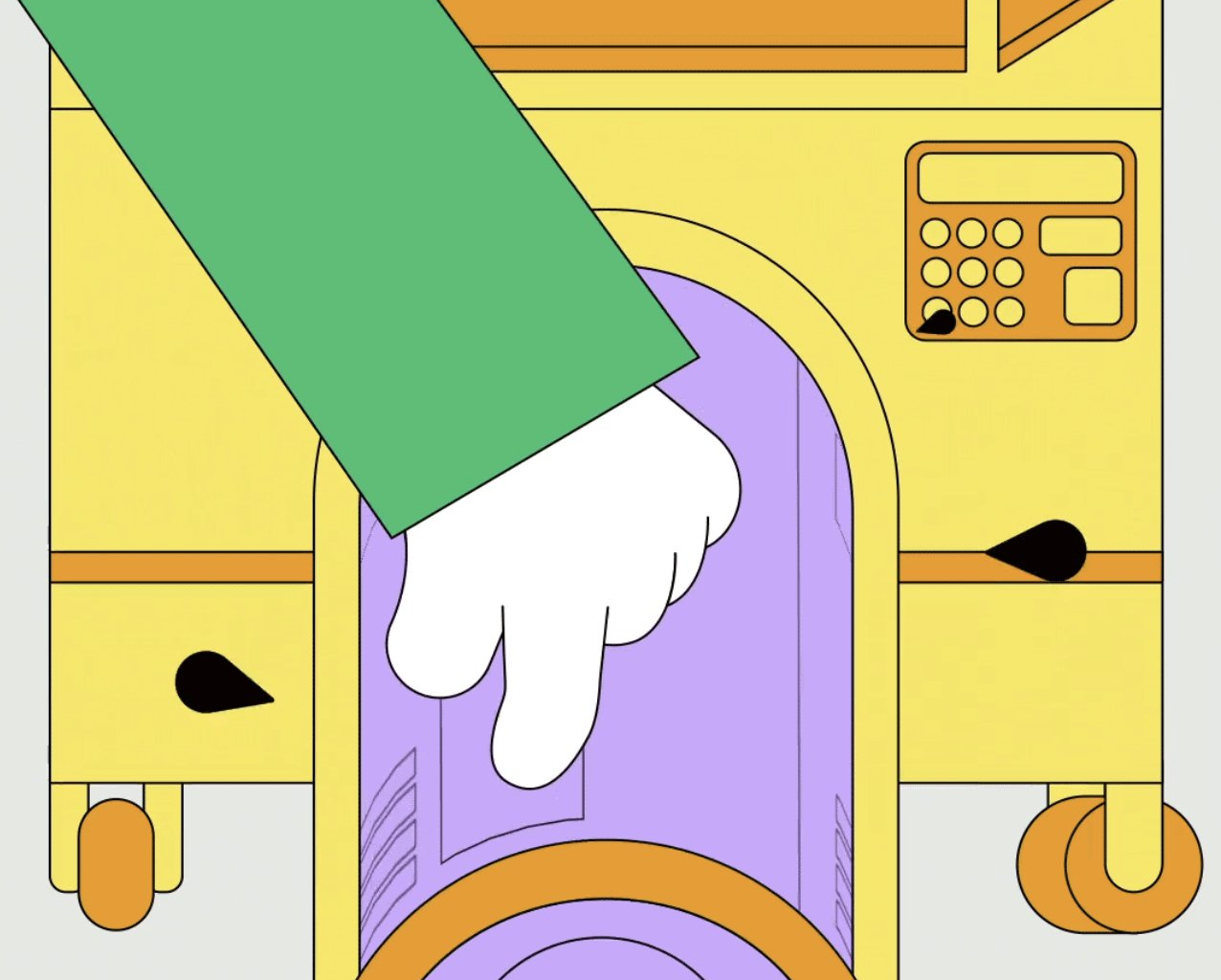

As I walk around London-based studio Make-Ready with founder Thomas Murphy – a print project that started in his South London garage all the way back in 2016 and has since become the world’s largest silkscreen print studio dedicated to fine-art – there are several screen prints undergoing an insanely laborious process of production, the craft of which is pretty much unparalleled at this scale. Amongst his explanations of everything from 26-layer file separations to mixing inks in-house, and the perfect conditions for developing a screen, we leaf through some hand drawn film positives for an Alex Katz print that he has been working on.

“It’s actually mental that I’m drawing them by hand,” he says. “I can draw quite well, and that’s a skill that I have, but that doesn’t matter, the print, as it stands, will have been made by the artist. But personally, for me, that’s not really the point at all. I know that we made it, and the artist knows that we made it, and the grease from the machine is still under my fingernails. I can go to bed at night knowing that we’ve done a great job.”

Far from the quiet process of reproduction that many perceive printmaking to be, the craft of the discipline has always been “an autonomous artform” in its own right, for printmakers like Joyce Gulley and Jan Dirk de Wilde, co-founders of Knust, an independent artist press based in the Netherlands. Widely regarded as one of the early pioneers for artist printmaking with the Risograph, Knust laid the foundations for the boom in this stencil printing technique back in the 80s and is still going strong, printing incredible artist books and editions with decades of expertise today.

Over the years at Knust, the studio’s prints have always stood as “interpretations that are somewhat disconnected from their originals”, shares Joyce. “In the early days when artists came just to have their catalogue printed, we said they were at the wrong address and tried to challenge them to think about making an artist book instead.” For Joyce and Jan, seeing machines like the Risograph as “perfect tools” for “specific tasks”, is a bit of a fault of the creative scene, one that ignores the real value in the place of the printmaker in letting go of specific expectations and “exploring and altering the process” – something that always “gives the most impressive results”, Joyce says.